East L.A. walkouts facts for kids

Quick facts for kids East Los Angeles Walkouts |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chicano Movement | |||

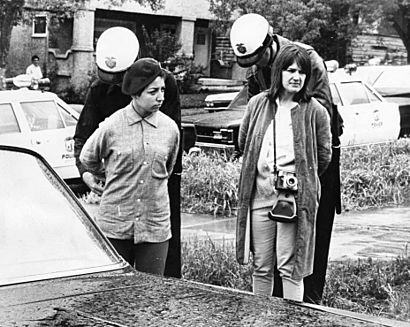

Students activists arrested during the walkouts

|

|||

| Date | March 6, 1968 | ||

| Location |

East Los Angeles, California

|

||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Goals | Education reform | ||

| Methods | Walkout | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

| Arrested | Sal Castro | ||

The East Los Angeles Walkouts, also called the Chicano Blowouts, were a series of student protests in 1968. Chicano students in Los Angeles Unified School District high schools walked out of classes. They were protesting unfair conditions and poor education. The first walkout happened on March 5, 1968.

Thousands of students in Los Angeles joined these protests. It was seen as the first big protest against unfair treatment by Mexican-American people in the United States. Before the walkouts, the FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, wanted police to watch out for minority movements. Some organizers, like Harry Gamboa Jr., were even called "dangerous" for their part in the protests.

Contents

Why Students Walked Out: The Background

In the 1950s and 1960s, Chicanos joined the national fight for civil rights. They worked to change laws and create social movements. Young Chicanos, especially, became active in politics. They had chances their parents did not. This movement became known as the Chicano Movement. It was similar to the larger Civil Rights Movement, but focused on equality for Chicano people.

Moctesuma Esparza, one of the main organizers, shared his story. He started activism in 1965 after a youth conference. He helped form a group called Young Citizens for Community Action. This group later became the Brown Berets. They continued fighting for Chicano equality in California.

After high school, Esparza went to UCLA. There, he and other Chicano students kept organizing. They also formed a group called UMAS. Its goal was to help more Chicano students get into colleges. UMAS members also mentored students at high schools with many minority students and high dropout rates.

Schools like Garfield, Roosevelt, Lincoln, Belmont, and Wilson had very high dropout rates. Garfield's rate was 58%, and Roosevelt's was 45%.

These poor school conditions were the main reason for the walkouts. Schools did not have enough teachers or staff. Classes often had 40 students. One school counselor might be responsible for 4,000 students. History classes often ignored Chicano history. Many teachers also treated their Chicano students unfairly.

To make things better, students decided to organize. Esparza, Larry Villalvazo, and other UMAS members worked with teacher Sal Castro. They helped hundreds of students plan to walk out in 1968. As the protests grew, the school board noticed. They agreed to meet with students and hear their demands.

Another important leader was Vickie Castro. She grew up in Eastside Los Angeles and knew the problems students faced. While at UCLA, Sal Castro asked her to join a youth conference. This conference helped young Chicanos become more aware of their struggles. Vickie Castro and David Sanchez were founding members of the Brown Berets. They held meetings at their coffee shop, La Piranya. Vickie Castro said the conference helped her find her "voice" and passion for justice.

The "Blowouts" Begin

On March 1, 1968, students at Wilson High School were the first to walk out. Wilson had one of the highest dropout rates in Los Angeles. This first walkout was not planned by the main organizers. About 200-300 students took part.

On March 5, about 2,000 students at Garfield High School started the first planned walkout. School officials called the police. Soon, an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 students walked out. They came from seven high schools in East Los Angeles: Wilson, Garfield, Roosevelt, Lincoln, Belmont, Jefferson, and Venice. About 75% of students at the East LA schools were Chicano.

Los Angeles public schools received money based on how many students were in class each day. By walking out before attendance was taken, students aimed to get attention by affecting school funds.

Vickie Castro, a strong female activist, played a key role. She realized few Chicano students went to college. This motivated her to help form the Brown Berets. This group supported the Chicano movement. They fought for better education, farm worker rights, and against police unfairness.

In March 1968, schools in East Los Angeles were known for being run down. They lacked college prep classes. Teachers were often poorly trained or unfair. Castro helped these students. She gave them courage to stand up for themselves. This helped students feel more pride in their Chicano heritage.

On March 6, 1968, Castro went to Lincoln High School. She pretended to apply for a teaching job. She distracted the principal while organizers entered the school. Their goal was to convince students to leave. She tried the same at Roosevelt High School, where she had been a student. But a teacher recognized her and threatened to call the police. When her attempt at Roosevelt failed, she used her car to pull down a fence. This fence was put up to keep organizers out. Castro's role was to inspire young people to fight school inequality.

The walkouts were a big step for the Chicano Movement. They gave young men and women a stronger sense of pride.

Student Demands for Change

After the walkouts, student leaders met with the board of education. They presented a list of demands. These demands focused on the most important issues affecting their education.

Improving Education

- No student or teacher should be punished for trying to improve schools.

- Schools with mostly Chicano students should offer bilingual and bicultural education. This means teaching in both English and Spanish. It also means including Mexican culture.

- Teachers and staff should learn Spanish. They should also learn about Mexican history and culture.

- Teachers and administrators who show unfairness towards Mexican or Chicano students should be removed. A community group would decide this.

- Textbooks should include Mexican and Chicano contributions to U.S. society. They should also show the unfairness Chicanos have faced.

- School leaders in Chicano-majority schools should be of Chicano background. Training programs should help more Chicanos become administrators.

- Information about how many students a teacher fails should be public. Teachers with high dropout rates in their classes should be reviewed by a community group.

Better School Management

- Schools should have managers for paperwork and maintenance. This would let administrators focus on teaching standards.

- School buildings should be available for community activities. Parents' groups, not just the PTA, should supervise these.

- Teachers should not be fired or moved because of their political views.

- Parents from the community should be hired as teacher's aides. They would get training and be seen as semi-professionals.

Better School Buildings and Resources

- The Industrial Arts program (shop classes) needs to be updated. Students need modern equipment and training for today's jobs.

- New high schools should be built in the area right away. The community should choose the names for these new schools.

- School libraries in East Los Angeles need more books and resources. Libraries should have enough materials in Spanish.

Key Moments: A Timeline

- March 1, 1968: Over 15,000 Chicano students, teachers, and community members walk out. They come from seven East L.A. high schools. These include Garfield, Roosevelt, Lincoln, Belmont, Wilson, Venice, and Jefferson High School. Some junior high students also join.

- March 11, 1968: The Chicano community forms the Educational Issues Coordinating Committee (EICC). They plan to share their concerns with the Los Angeles County Board of Education. The Board agrees to meet.

- March 28, 1968: The meeting between the Board of Education and the EICC happens. Over 1,200 community members attend. The EICC presents 39 demands. The Board rejects the demands, and students walk out of the meeting.

- March 31, 1968: Thirteen Chicano walkout organizers are arrested. They are known as the Eastside 13. They are accused of organizing the walkouts. Those arrested include students, Brown Berets, and newspaper editors. Students and community members protest outside the Hall of Justice. They demand the release of the 13. Twelve are released. Sal Castro, a teacher and key organizer, faces the most accusations and is held the longest.

- June 2, 1968: Sal Castro is released on bail. But he loses his teaching job at Lincoln High School. 2,000 people protest to demand he get his job back.

- September-October 1968: Students and community members hold sit-ins at the LA Board office. They stay until Sal Castro gets his teaching job back. The board eventually allows Castro to return.

What Happened Next

Many of the students who organized the walkouts became successful in their careers. Moctesuma Esparza, one of the "East L.A. 13," became a successful film producer. He helped more Chicanos get jobs in Hollywood. Harry Gamboa Jr. became an artist and writer. Carlos Montes, a Brown Berets leader, faced legal issues but was later found not guilty.

Paula Crisostomo became a school administrator. She continues to fight for education reform. Vickie Castro was elected to the Los Angeles Los Angeles Unified School District Board of Education. Carlos Muñoz, Jr., became a respected teacher and researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. Carlos R. Moreno became a judge for the Supreme Court of California.

The student actions of 1968 inspired many later protests. These included walkouts against California Proposition 187 in 1994. There were also student walkouts in 2006 against H.R. 4437, and in 2009 against Arizona's SB1070. Students also walked out in 2007 to support a holiday for César Chávez.

The Walkouts also led to many films, documentaries, and books. Some tell the direct story of the Blowouts. Others share similar stories. Examples include Stand and Deliver, Freedom Writers, and Precious Knowledge.

Images for kids

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |