Elizabeth Kenny facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elizabeth Kenny

|

|

|---|---|

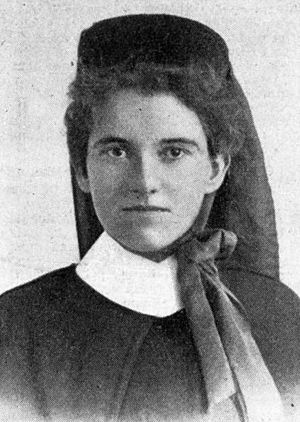

Elizabeth Kenny in 1950

|

|

| Born | 20 September 1880 |

| Died | 30 November 1952 (aged 72) Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia

|

| Nationality | Australian |

| Other names | Lisa |

| Citizenship | Australian |

| Occupation | Nurse |

Elizabeth Kenny (born September 20, 1880 – died November 30, 1952) was an Australian nurse. She helped many people with polio using a new and different method. Doctors at the time usually kept polio patients' muscles still. But Elizabeth Kenny believed it was better to move them. Her ideas about moving muscles became a big part of what we now call physical therapy.

Her life story was told in the 1946 film Sister Kenny. Actress Rosalind Russell played Kenny and was nominated for an Academy Award for her performance.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Early Life and Learning

Elizabeth Kenny was born in Warialda, New South Wales, Australia, in 1880. Her parents were Mary and Michael Kenny. Her family called her "Lisa." She learned at home and later went to schools in New South Wales and Nobby, Queensland.

When she was 17, she broke her wrist falling from a horse. Her father took her to Dr. Aeneas McDonnell in Toowoomba. While recovering, Kenny studied Dr. McDonnell's anatomy books. This started a long friendship with him; he became her mentor. Kenny said this accident made her interested in how muscles work. She even made her own model skeleton to study.

From age 18 until her mid-twenties, she worked as a nurse in the Clifton area. In 1907, Kenny lived with a cousin in Guyra, New South Wales. She said she got basic nursing training there, but there is no official record of it. She also helped farmers sell their crops. The title "Sister" for nurses in some countries does not mean they are part of a religious group.

Her Work as a Nurse

In 1909, Kenny returned to Nobby and started working as a nurse. She even paid a tailor to make her a nurse's uniform. In 1911, she used money she earned to open a small hospital called St. Canice's in Clifton. There, she helped people recover and delivered babies. She also treated her first confirmed cases of infantile paralysis (polio) with a local doctor's help.

Kenny wrote in her 1943 autobiography that she treated her first polio cases in 1910. She said she was confused by the illness and asked Dr. McDonnell for advice. He told her to treat the symptoms as they appeared. She noticed the patients' muscles were tight. So, she applied hot compresses and warm wool blankets to their legs. Several children got better with no serious problems. This story is a famous medical legend, but there are no other records to prove it.

Serving in World War I

In 1915, Kenny volunteered to be a nurse in World War I. Even though she wasn't officially trained, nurses were greatly needed. She was accepted and worked on "Dark Ships." These ships traveled between Australia and England with no lights on. They carried supplies and soldiers one way, and wounded soldiers and goods back. Kenny made 16 round trips on these dangerous journeys.

In 1917, she earned the title "Sister." In the Australian Army Nurse Corps, this title is like a first lieutenant. She used this title for the rest of her life. Some people criticized her for using it because it was usually for officially qualified nurses. But Kenny had earned the rank during her wartime service. Near the end of the war, she worked as a matron (head nurse) at a soldiers' hospital near Brisbane. She was honorably discharged and received a pension.

Reports from the 1930s say Kenny developed her method while caring for patients with meningitis on troopships during the war.

Helping Back Home

After the war, Kenny was very tired. But she helped run a temporary hospital in Nobby, Queensland for people sick with the 1919 flu epidemic. After the flu ended, Kenny traveled to Europe to visit doctors. When she returned to Nobby, a friend asked her to care for her daughter, Daphne Cregan. Daphne had a condition called cerebral diplegia. Kenny worked with Daphne for three years. This experience, along with her wartime work, likely helped her develop her polio treatments. Elizabeth Kenny also adopted a daughter named Mary Stewart, who became one of her best researchers.

Instead of staying home, Kenny continued nursing from her mother's house. She often traveled to patients by motorcycle or car. Once, a friend's daughter, Sylvia, was hurt by a horse-drawn plow. Kenny quickly made a stretcher from a cupboard door. She fastened Sylvia to it and took her 26 miles (42 km) to Dr. McDonnell's office. Sylvia recovered, thanks to Kenny's careful help. Kenny improved the stretcher for ambulance services. For three years, she sold it as the "Sylvia Stretcher" in Australia, Europe, and the United States. She gave all the money to the Australian Country Women's Association.

Treating Polio Patients

When sales of the stretcher slowed, Kenny went back to home nursing. In 1929, she met a family who asked her to care for their niece, Maude, who had polio. At that time, doctors usually put splints on affected limbs to keep them still. But after 18 months with Kenny, Maude could walk, get married, and have a child. Newspapers in Townsville called it a "cure."

In 1932, Queensland had many polio cases. The next year, people helped Kenny set up a simple polio treatment center in Townsville. After helping more children, she moved into a hotel. The Queensland Health Department officially looked at Kenny's work in 1934. This led to Kenny clinics opening in several Australian cities. The Sister Kenny Clinic in Rockhampton is now a protected heritage site.

During these years, Kenny developed her treatment methods and became well-known in Australia. She strongly disagreed with using plaster casts or braces to keep children's bodies still. Kenny wanted to treat children during the early, acute stage of polio with hot compresses. However, doctors would not let her treat patients until later. She created a careful plan of gentle "exercises" to help muscles work again. She secretly treated a patient in the acute stage at her Brisbane clinic. That child and others recovered with fewer problems than those who wore braces.

In 1937, she published a book about her work. She also wrote another book, The Treatment of Infantile Paralysis in The Acute Stage, which was published in the United States. Her most complete book was written with Dr. John Pohl in 1943.

Between 1935 and 1940, Kenny traveled across Australia, helping to open clinics. She also went to England twice and set up a clinic there. From 1936 to 1938, the Queensland Government looked into Kenny's work. They said that stopping the use of splints was a "serious error." But they also said her clinic was "admirable." The government continued to support Kenny's work.

Work in the U.S.

In 1940, the New South Wales government sent Kenny and her adopted daughter Mary to America. Mary was an expert in Kenny's methods. They traveled across the country, showing her treatment to American doctors. In Minneapolis, Minnesota, doctors Miland Knapp and John Pohl were impressed. They told her to stay. Minneapolis became Kenny's home base in America for 11 years. In 1943, Kenny wrote that over 300 doctors attended her classes at the University of Minnesota.

During this time, Kenny treatment centers opened across America. The most famous was the Sister Kenny Institute in Minneapolis. She received special degrees from universities. She even had lunch with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who also had polio. They talked about his treatment.

In 1951, Kenny was named the most admired woman in the Gallup Poll. She was the only woman in 10 years to be more admired than Eleanor Roosevelt. The Sister Kenny Foundation was created to support her work in the United States.

Kenny's success was debated. Many Australian doctors questioned her methods. Kenny publicly argued against these criticisms, which was unusual for a self-taught nurse. This caused problems between Kenny and medical groups. In the United States, Kenny faced many doubtful doctors. Some doctors at first thought she was a "quack." But many changed their minds when they saw how her method helped patients.

The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP) initially supported Kenny. But they stopped after disagreements. Kenny was a strong and outspoken woman, which sometimes bothered the NFIP and many doctors. Still, her treatment method continued to help hundreds of children with polio.

Later Years and Passing

In her final years, Kenny traveled in America, Europe, and Australia. She wanted more people to accept her treatment method. She also developed ways to treat other serious illnesses. She returned home to Toowoomba in 1951. Elizabeth Kenny passed away on November 30, 1952, from problems related to Parkinson's disease. She was buried next to her mother in Nobby Cemetery.

Her Lasting Impact

Between 1934 and her death in 1952, Kenny and her team treated thousands of patients. But her methods were used to help many more polio victims worldwide. The stories of those she helped are part of her legacy. Another part is The Kenny Concept of Infantile Paralysis, and Its Treatment, a book written with Dr. John Pohl. Her most lasting legacy is the Sister Kenny Rehabilitation Institute in Minneapolis.

In Kenny's home village of Nobby, the Sister Kenny Memorial House has many items from her life. It also has her letters, papers, and newspaper clippings. In Toowoomba, the Sister Elizabeth Kenny Memorial Fund gives scholarships to students at the University of Southern Queensland. These students plan to work in rural areas of Australia. In Townsville, a memorial and children's playground were opened in 1949 to honor her.

Sister Kenny is mentioned in the TV movie An American Christmas Carol. Her treatments are also suggested to help Livy Walton recover from polio in The Waltons TV show.

Cartoonist Al Capp, who had a disability, worked with the Sister Kenny Foundation. He made public appearances and created artwork to help raise money. He also visited hospitals to cheer up children with disabilities.

Actor Alan Alda says that Sister Kenny's treatments helped him fully recover from polio as a child. He wrote in his book that he has no doubt they worked. Actor Martin Sheen also shared that he got polio as a child. He said he regained the use of his legs only because his doctor used Sister Kenny's method.

People Who Received Treatment

- Alan Alda, actor

- Martin Sheen, actor

- Robert Anton Wilson, writer

- Marjorie Lawrence, Australian opera singer

- Rosalind Russell's nephew

- Peg Kehret, American author

- Dinah Shore, singer

- Joy McKean, singer

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Elizabeth Kenny para niños

In Spanish: Elizabeth Kenny para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |