Equus (genus) facts for kids

Equus is a group of mammals that includes horses, asses (donkeys), and zebras. It is the only group of horses still alive today, with seven different species. These animals are known for having just one toe on each foot. They are very good at living in different kinds of grasslands.

The word equine refers to any animal in the Equus group. Many Equus species are now extinct, meaning they only exist as fossils. This group likely started in North America and then quickly spread to other parts of the world. Equines are odd-toed ungulates, which means they have an odd number of toes. They have thin legs, long heads, fairly long necks, and manes (which stand up on most species). Their tails are also long. All Equus animals are herbivores, meaning they eat plants. They are mostly grazers, eating grass. They have simpler digestive systems than animals like cows, but they can still live on plants that are not very high quality.

You can find wild equines in Africa and Asia. Many other equines live as feral animals, meaning they used to be tame but now live in the wild. Wild equines often live in a "harem" system. This means one adult male (called a stallion) lives with several females (mares) and their young (foals). Other groups might live in a territory where males control areas with food and water to attract females. In both systems, mothers usually take care of the foals, but males might help too. Equines talk to each other using sounds and body language. Sadly, human activities have put many wild equine populations in danger. Out of the seven living species, only the plains zebra is still common and widespread.

The one-toed horses we see today developed from smaller, three-toed horses. These older horses lived more in forests and wooded areas. Before humans came along, horses were much more diverse and lived in many more places, but we don't know exactly how many species there were.

Contents

Biology

Physical characteristics

Equines come in different sizes, but they all have long heads and necks. Their thin legs support their weight on just one toe, which developed from their middle toe. The Grévy's zebra is the biggest wild species. It can stand up to 13.2 hands (54 inches, 137 cm) tall and weigh up to 405 kg (890 lb). Domesticated horses have an even wider range of sizes. Large draft horses are usually at least 16 hands (64 inches, 163 cm) tall and can reach 18 hands (72 inches, 183 cm). They can weigh from about 700 to 1,000 kilograms (1,500 to 2,200 lb). Some miniature horses are only 30 inches (76 cm) tall when they are adults. Male and female equines are usually about the same size.

Equines are built for running and traveling long distances. Their teeth are perfect for grazing. They have large front teeth (incisors) that cut grass blades. Their back teeth (molars) are ridged and good for grinding food. Male equines have spade-shaped canine teeth, called "tushes," which they can use to fight. Equines have good senses, especially their eyesight. Their ears are moderately long and can move to help them find where a sound is coming from.

Most wild equines have a dun-colored coat with "primitive markings." These markings include a dark stripe down their back and often stripes on their legs and shoulders. Only the mountain zebra does not have a dorsal stripe. In domestic horses, you can find dun colors and these markings in many breeds. Scientists have debated for over a hundred years why zebras have bold black-and-white stripes. Recent studies (from 2014) suggest the stripes protect them from biting flies. These insects seem less attracted to striped coats. Zebras live in areas with the most fly activity compared to other wild equines.

Most equines have manes that stand up and long tails with a tuft of hair at the end. Domestic horses are an exception; they have long manes that lie over their necks and long tail hair that grows from the top of their tail. The coats of some equine species change with the seasons. They shed their fur in some areas and grow thick coats in winter.

Ecology and daily activities

Wild equines live in different parts of Africa and Asia. The plains zebra lives in grassy areas and savannas in Eastern and Southern Africa. The Mountain zebra lives in the mountains of southwest Africa. Other equine species prefer drier places with fewer plants. The Grévy's zebra lives in thorny scrubland in East Africa. The African wild ass lives in rocky deserts of North Africa. The two Asian wild ass species live in the dry deserts of the Near East and Central Asia. Przewalski's wild horse lives in the deserts of Mongolia. Only the plains and Grévy's zebras live in the same areas.

Besides wild populations, domesticated horses and donkeys are found all over the world because of humans. In some places, there are also feral horses and donkeys. These are descendants of domesticated animals that either escaped or were set free.

Equines are "hindgut fermenters," which means they digest their food in a special part of their large intestine. They like to eat grasses and sedges. But if their favorite foods are scarce, especially asses, they might also eat bark, leaves, buds, fruits, and roots. Equines have a simpler digestive system than animals like cows. However, they can still live on lower quality plants. After food goes through the stomach, it enters a sac-like part called the cecum. Here, tiny organisms break down cellulose (a part of plant cell walls). Digestion is faster in equines than in ruminants. It takes 30–45 hours for a horse, compared to 70–100 hours for a cow. Equines might spend 60-80 percent of their day eating. This depends on how much food is available and how good it is. In the African savannas, plains zebras are "pioneer grazers." They eat the taller, less nutritious grass, making it easier for other animals like blue wildebeests and Thomson's gazelles to eat the shorter, more nutritious grasses underneath.

Wild equines may sleep for about seven hours a day. During the day, they often sleep standing up. At night, they lie down. They often rub against trees, rocks, and other things. They also roll around in dust to protect themselves from flies and skin irritation. Most wild equines, except the mountain zebra, can roll over completely.

Social behavior

Equines are social animals. They have two main ways of living in groups. Horses, plains zebras, and mountain zebras live in stable family groups called harems. These groups have one adult male, several females, and their young. These groups have their own areas that can overlap with other groups. They tend to move around a lot. The group stays together even if the family stallion dies or is replaced. Plains zebra groups can gather into very large herds. They might even form temporary smaller groups within a herd. This allows individuals to meet others outside their usual family group. This behavior is rare among harem-holding animals. It is mostly seen in primates like the gelada and the hamadryas baboon.

Females in a harem benefit because the male gives them more time to eat. He also protects their young and keeps away predators or other males. Within a harem, females have a ranking system. The mares who joined the group earliest are usually higher in rank. Harems travel in a specific order. The highest-ranking mares and their young lead the group. The next highest-ranking mare and her young follow, and so on. The family stallion usually stays at the back. Social grooming is important for reducing arguments and keeping social bonds strong. This involves animals rubbing their heads against each other and gently nipping with their teeth and lips. Young equines of both sexes leave their family groups as they grow up. Females are often taken by outside males to become part of their harems.

In both types of equine social systems, extra males form bachelor groups. These are usually young males who are not yet ready to start their own harem or territory. Among plains zebras, males in a bachelor group have strong bonds and a clear ranking system. Fights between males usually happen over females who are ready to mate. These fights involve biting and kicking.

Communication

When equines meet for the first time, or after being separated, they might greet each other by rubbing and sniffing noses. Then they might rub and press their shoulders together and rest their heads on each other. This greeting usually happens between males in harems or territories, or between bachelor males playing.

Equines make many different sounds. A loud snort often means they are alarmed. Squealing usually means they are in pain, but bachelor males also squeal when they are play-fighting. The sounds equines make to keep in touch vary. Horses whinny and nicker. Plains zebras bark. Asses and Grévy's zebras bray. Equines also communicate with body language. Their flexible lips allow them to make many different facial expressions. Their head, ear, and tail positions also send messages. An equine might show it intends to kick by laying its ears back and sometimes lashing its tail. Flattened ears, bared teeth, and sudden head movements can be used as threats, especially among stallions.

Reproduction and life cycle

The time a female is pregnant (gestation) varies by species, but it is usually around 11 to 13 months. Most mares will be ready to mate again within a few days after giving birth, depending on conditions. Usually, only one foal is born. The foal can run within an hour of being born. Within a few weeks, foals will try to eat grass, but they might continue to nurse from their mothers for 8–13 months. Species that live in dry places, like the Grévy's zebra, nurse for longer periods. They also do not drink water until they are three months old.

In species that live in harems, mothers mostly care for their foals. But if predators threaten them, the whole group works together to protect all the young. The group forms a protective line with the foals in the center. The stallion will rush at any predators that come too close. In species where males control territories, mothers might gather into small groups. They leave their young in "kindergartens" under the guard of a territorial male while they go look for water. Grévy's zebra stallions might even look after a foal in their territory to make sure the mother stays, even if the foal is not theirs.

Human relations

Domestication

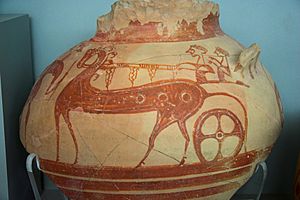

The oldest proof that horses were tamed comes from sites in Ukraine and Kazakhstan. This was about 4000-3500 BC. By 3000 BC, horses were fully domesticated. By 2000 BC, many more horse bones were found in human settlements in northwestern Europe. This shows that tamed horses had spread across the continent. The clearest proof of domestication comes from sites where horse remains were buried with chariots in graves. This was in the Sintashta and Petrovka cultures around 2100 BC. Studies of horse DNA show that very few wild male horses, possibly from just one family line, became ancestors of domestic horses. However, many female horses were part of these early tamed groups.

The Przewalski's horse has been proven not to be an ancestor of the domestic horse. Even though they can have babies together that can also have babies, they are different. The split between Przewalski's horse and the domestic horse happened an estimated 120,000–240,000 years ago, long before humans started taming horses. Of the horse species, it is the European wild horse, also called the "tarpan," that shares ancestors with the modern domestic horse. It is also thought that tarpans that lived into modern times might have mixed with domestic horses.

Evidence from old sites, geography, and language suggests that the donkey was first tamed by people who moved around in North Africa over 5,000 years ago. These animals helped people deal with the drier climate in the Sahara and the Horn of Africa. Genetic evidence shows that donkeys were tamed twice from two different groups of wild donkeys. It also points to one main ancestor, the Nubian wild ass. People tried to tame zebras, but it was mostly unsuccessful. However, Walter Rothschild did train some zebras to pull a carriage in England.

Conservation issues

Humans have greatly affected wild equine populations. Threats to wild equines include losing their homes (habitat destruction) and problems with local people and their farm animals. Since the 1900s, wild equines have been greatly reduced in many areas where they used to live. Their populations are now scattered. In recent centuries, two subspecies, the quagga and the tarpan, became extinct. Only the plains zebra is still common and widespread.

The IUCN (a group that tracks endangered species) lists the African wild ass as critically endangered. This means it is at very high risk of becoming extinct. The Grévy's zebra, mountain zebra, and Przewalski's horse are listed as endangered. The Onager is vulnerable, meaning it is at high risk. The kiang is at lower risk, and the plains zebra is of least concern. The Przewalski's horse was thought to be extinct in the wild from the 1960s to 1996. But thanks to successful breeding programs, it has been brought back to live in the wild in Mongolia.

The protection of feral horses causes a lot of debate. For example, in Australia, they are seen as an invasive species that does not belong there. They are often considered pests, but they also have some cultural and economic value. In the United States, feral horses and burros are generally seen as an introduced species. This is because they are descendants of domestic horses brought to the Americas from Europe. Many livestock farmers see them as pests. But others believe that E. ferus caballus is a species that once lived in the Americas and should be protected. Today, some free-roaming horses and burros have federal protection. They are called "living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West" under a law from 1971. The United States Supreme Court also ruled that these animals are legally considered wildlife.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Equus para niños

In Spanish: Equus para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |