Domestication of the horse facts for kids

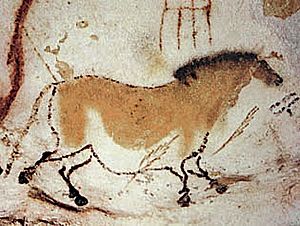

For a long time, scientists have wondered exactly when and how horses became domesticated. This means when they stopped being wild animals and started living with humans. Even though horses appeared in Paleolithic cave art as far back as 30,000 BC, these were wild horses. People probably hunted them for food.

The clearest signs of horses being used for travel come from chariot burials around 2000 BC. However, more and more evidence suggests that horses were first tamed in the Eurasian Steppes around 3500 BC. Discoveries in Kazakhstan, linked to the Botai culture, point to this area as the earliest place where horses were domesticated. Other studies suggest it happened around 3000 BC in what is now Ukraine and Western Kazakhstan.

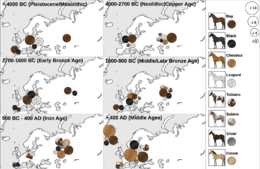

Genetic studies now show that the ancestors of modern horses were likely tamed in the Volga–Don area. This is in the Pontic–Caspian steppe region of eastern Europe, around 2200 BC. From there, horses spread across Eurasia. They were used for travel, farm work, and in wars. Scientists have found genetic changes in horses that helped them spread so successfully. They think stronger backs and a calmer nature made horses better for riding.

Contents

What is Domestication?

The exact date horses were domesticated depends on what "domestication" means. Some scientists say it means humans controlling how animals breed. We can see this in old horse bones by changes in their size. Other researchers look at more clues. These include signs of horses working, like changes in their teeth. They also look at tools, art, and how people lived.

There is proof that people kept horses for meat and milk before they trained them to work. Trying to date domestication using genetics or bones assumes that wild and tame horses became genetically different. This did happen, but it's hard to know if wild and tame horses mixed for a while.

If we use a wider definition of domestication, which includes many clues, the date changes. Evidence from 4000 BCE includes signs of bits on horse teeth. It also includes changes in how people butchered horses and how they lived. Horses also started appearing as symbols of power in artifacts and in human graves. But big changes in horse size, linked to domestication, happened later, around 2500–2000 BCE. This was seen in horse remains in Hungary.

Horses spread across Eurasia for travel, farm work, and warfare. Early harnesses for horses and mules were not very good. They were like those used for oxen. Much later, padded horse collars were invented. These allowed horses to use their full strength.

Ancestors of Modern Horses

A study in 2005 looked at the DNA of many horse-like animals. This included fossils from 53,000 years ago and modern horses. All these animals came from one single ancestor. This group included three different species: Hippidion from South America, the New World stilt-legged horse from North America, and Equus, the true horse.

The true horse included ancient horses and the Przewalski's horse. It also included what is now the modern domestic horse. This group lived across a wide area from North America to central Europe. The true horse died out in the Americas about 10,000 years ago. But it survived in Eurasia. All domestic horses today seem to have come from these Eurasian horses.

So, the domestic horse today is called Equus ferus caballus. There are no truly wild horses left that are the original ancestors of modern domestic horses. The Przewalski's horse is different from modern horses. It has 66 chromosomes, while domestic horses have 64. Their DNA also shows they are a separate group. Scientists think Przewalski's horses came from a different group of wild horses in eastern Eurasia.

Ancient wild horses, like those in the cave paintings of Lascaux, probably looked like Przewalski's horses. They had big heads, dun (yellowish-brown) coats, thick necks, stiff upright manes, and short, strong legs.

During the Ice Age, early humans hunted horses for meat in Europe and across Eurasia. Many kill sites exist, and cave paintings show what these horses looked like. Many of these Ice Age horses died out because of fast climate changes. Humans also hunted them, especially in North America, where horses completely disappeared.

Before DNA research, people thought there were four main types of wild horses. These types were believed to have adapted to their environments before domestication. Some thought they were different species, others that they were just different forms of the same species. However, newer studies show there was only one wild species. All the different body types came from selective breeding after domestication.

Two "wild" groups, believed to have never been tamed, survived until recent times: Przewalski's horse and the Tarpan. The Tarpan died out in the late 1800s. Przewalski's horse is endangered. It disappeared from the wild in the 1960s but was brought back to Mongolia in the 1990s. Even though some thought Przewalski's horses were ancestors of modern horses, recent genetic studies show they are not.

Genetic Clues to Domestication

A 2014 study compared DNA from ancient horse bones (before domestication) with modern horse DNA. They found 125 genes linked to domestication. Some genes affected physical traits like muscles and heart strength. Others were linked to how horses think and behave. These genes likely helped in taming horses, affecting their social behavior, learning, fear, and how agreeable they were.

Scientists can study the DNA of male horses (stallions) and female horses (mares) separately. DNA from mares (called mitochondrial DNA or mtDNA) suggests that many different female lines were involved in domestication. This means at least 77 different ancient mares contributed to modern horses. However, DNA from stallions (Y-chromosome or Y-DNA) shows much less variety. This first suggested that only a few stallions were tamed. But newer studies of ancient DNA show that Y-chromosome variety was higher a thousand years ago. The low variety today might be because popular breeds like the Arabian and Thoroughbred used only a few famous male ancestors.

A 2012 study looked at 300 modern work horses and reviewed older studies. It suggested that horses were first tamed in the western part of the Eurasian steppe. Both tamed stallions and mares spread from this area. Then, more wild mares were added from local herds. Wild mares were easier to handle than wild stallions. Most other parts of the world were ruled out as places where horses were first tamed. This was either due to unsuitable climates or no evidence of domestication.

Genes from the Y-chromosome are passed only from father to son. Modern domestic horses show very little genetic variety in these genes. This means that only a few male horses were tamed. It's unlikely that many male offspring from wild stallions and domestic mares were used for early breeding.

Genes from mitochondrial DNA are passed from mother to all her offspring. Studies of modern and ancient horse DNA show a lot of variety in mitochondrial DNA. This means that many different mares were included in the breeding of early domestic horses. This variety helps scientists identify "haplogroups," which are groups of closely related horses. Eighteen main haplogroups are known. Some haplogroups are found more in certain parts of the world. This shows that local wild mares were added to the tamed horse groups.

In 2018, a study compared ancient horse DNA, including some from Botai. It showed that modern domestic horses are not closely related to the horses found at Botai. Instead, Przewalski’s horses were identified as wild descendants of horses kept at Botai. This suggests a big genetic change happened when horses were domesticated. It also happened when human populations grew in the Early Bronze Age. Later research confirmed that horse groups from other early domestication sites did not influence modern domestic horses much.

In 2021, over 150 scientists studied 264 ancient horse genomes from Eurasia. Their findings, published in Nature, showed that modern horses likely came from the Volga-Don area. This is in the Pontic–Caspian steppe grasslands of Western Eurasia. Both the Tarpan and Przewalski’s horse were related to different ancient horse groups than modern domestic horses (called DOM2).

Researchers also saw how modern domestic horses (DOM2) quickly spread across Eurasia. They replaced other local horse groups from about 2000 BCE onwards. The DOM2 genetic type is found in horses buried with early chariots. These are linked to the Sintashta culture. DOM2 horses also appeared in some areas before chariots. This suggests that both riding and chariots helped them spread.

Genetic data also helps explain why this domestication event was so important. The horses that led to modern domestic horses show signs of being chosen for better movement and behavior. Changes in certain genes (GSDMC and ZFPM1) are linked to this. The GSDMC gene might have made horses' backs stronger. The ZFPM1 gene is linked to mood. Scientists think this made horses calmer and easier to train. Being strong and calm made them perfect for riding and other uses.

Archaeological Clues

Archaeological evidence for horse domestication comes from three main sources:

- Changes in the bones and teeth of ancient horses.

- Changes in where ancient horses lived, especially when they appeared in places where wild horses hadn't been before.

- Archaeological sites with tools, pictures, or signs of human behavior linked to horses.

Examples include horse remains found in human graves. Also, changes in the ages and sexes of horses killed by humans. The appearance of horse corrals, and equipment like bits or other horse tack. Horses buried with equipment like chariots. And pictures of horses being ridden, driven, or used for work.

No single clue proves domestication alone. But when all the evidence is put together, it becomes very convincing.

Horses Buried with Chariots

The clearest evidence of domestication comes from sites where horse bones were buried with chariots. This happened in at least 16 graves of the Sintashta and Petrovka cultures. These sites are in the steppes of southern Russia and northern Kazakhstan. These cultures existed from about 2100–1700 BCE. Some graves had up to eight sacrificed horses placed in or near them.

In all these chariot graves, the heads and hooves of two horses were placed in a grave that once held a chariot. We know chariots were there from the marks of two spoked wheels on the grave floors. Also, two disk-shaped antler "cheekpieces" were found next to each horse head. These were an early type of bit shank or bit ring. They had prongs that would press against the horse's lips when the reins were pulled. These studded cheekpieces were a new, strong way to control horses. They appeared at the same time as chariots.

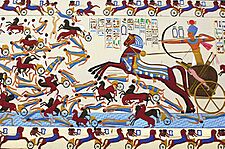

All the chariot graves had wheel marks, horse bones, weapons, human bones, and cheekpieces. Because the horses were buried in pairs with chariots and studded cheekpieces, it's very clear these steppe horses from 2100–1700 BCE were domesticated. Soon after these burials, domestic horses spread very quickly across Europe. Within about 500 years, horse-drawn chariots appeared in Greece, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. Another 500 years later, they had spread to China.

Skeletal Clues of Domestication

Some researchers believe an animal is "domesticated" only when it shows physical changes from being bred in captivity. Before that, they call them "tamed." These scientists point to changes in horse bones found around 2500 BCE in eastern Hungary. These bones showed more variety in size, meaning both larger and smaller horses survived under human care. They also showed a decrease in average size, possibly because horses were kept in pens and had limited diets. Horse groups with these changes were likely domesticated. Most evidence suggests humans controlled horses more after 2500 BCE. However, more recent finds in Kazakhstan show smaller, more slender limbs, typical of penned animals, dating to 3500 BCE.

Botai Culture Clues

Some of the most interesting evidence for early domestication comes from the Botai culture in northern Kazakhstan. The Botai people were hunters who seemed to start riding horses to hunt the many wild horses there between 3500 and 3000 BCE. Botai sites had no bones from cattle or sheep. The only tamed animals, besides horses, were dogs. Botai settlements had many pit houses. Their garbage piles contained tens of thousands of animal bones, mostly from horses (65% to 99%).

Evidence of horse milking was also found at these sites. Horse milk fats were soaked into pottery pieces dating back to 3500 BCE. Earlier hunters in the same area did not hunt wild horses as successfully. They lived in smaller, less permanent settlements. The Botai hunters killed whole herds of horses, likely in big hunting drives. Riding horses might explain how they became such skilled hunters and built larger, more permanent settlements.

Some researchers argued that all Botai horses were wild. They said that the Botai hunters hunted horses on foot. They noted that Botai horse bones showed no changes from domestication. Also, the age of the slaughtered horses looked like a natural wild herd, not a tamed one. However, these arguments were made before a horse corral was found at Krasnyi Yar in 2006. Also, mats of horse dung were found at two other Botai sites. Current findings still support the idea that the Botai people had domesticated horses.

A 2018 study showed that Botai horses did not contribute much to the genes of modern domestic horses. This means a different domestication event must have led to modern horses. Genetic evidence also links Botai horses to Przewalski's horse. This has led to debates about whether Przewalski's horses are truly wild or if they are wild descendants of tamed Botai horses.

Bit Wear on Teeth

The presence of bit wear on horse teeth shows that a horse was ridden or driven. The earliest such evidence from Kazakhstan dates to 3500 BCE. If there's no bit wear, it doesn't mean the horse wasn't tamed. Horses can be ridden without bits using a noseband or a hackamore. These materials don't leave marks on teeth and don't last for thousands of years.

Regular use of a bit can create wear marks on the front corners of the lower second premolars. The bit usually rests on the "bars" of the mouth, where there are no teeth. For the bit to touch the teeth, a human must move it, or the horse must move it with its tongue. Wear can happen if the horse bites the bit. It can also happen if a human pulls the reins very hard.

Modern tests showed that even soft bits made of rope or leather can cause wear marks. They also showed that marks 3mm deep or more do not appear on the teeth of wild horses. However, some researchers disagree with these findings.

Wear marks of 3mm or more were found on seven horse premolars at two Botai culture sites. These date to about 3500–3000 BCE. These are the earliest clear examples of this tooth damage found at an archaeological site. They appeared 1,000 years before any skeletal changes linked to domestication.

Dung and Corrals

Scientists found layers of horse dung at Botai and Krasnyi Yar in northern Kazakhstan. The dung was thrown into unused house pits. Collecting and disposing of horse dung suggests that horses were kept in corrals or stables. An actual corral, dating to 3500–3000 BCE, was found at Krasnyi Yar. It was a circular fence made of post holes. The soil inside the fence had ten times more phosphorus than outside. This phosphorus likely came from manure.

Geographic Spread

When horse remains appear in human settlements in areas where wild horses didn't live before, it's another sign of domestication. Pictures of horses appeared in Upper Paleolithic caves in France. This shows wild horses lived outside the Eurasian steppes and were hunted by early humans. But a lot of horse remains in one place suggests animals were captured and kept, which points to domestication.

Around 3500–3000 BCE, horse bones became more common in archaeological sites outside the Eurasian steppes. They appeared in central Europe, the Danube valley, and the Caucasus. Horses were rare in these areas before. As their numbers grew, larger horses also started to appear. This spread happened at the same time as the Botai culture, where horses were likely corralled and ridden.

Wild horses were hunted in parts of Europe, but their bones were rare in many areas like Greece and the British Isles. In contrast, wild horse bones made up over 40% of animal bones in hunter-gatherer camps in the Eurasian steppes.

Horse bones were rare or missing in ancient garbage piles in western Turkey, Mesopotamia, most of Iran, and Central Asia. In central Turkey, horse bones were less than 10% of all horse-like animals. Most of these were onagers or other wild asses. Wild horses apparently did not live in these areas.

Other Signs of Spread

In the Northern Caucasus, the Maikop culture (around 3300 BC) had both horse bones and images of horses. A painting of nineteen horses was found in one Maikop grave. The widespread appearance of horses in Maikop sites suggests that horseback riding began during this period.

Later, images of horses appeared in Mesopotamia during the Akkadian Empire (2300–2100 BCE). These horses had short ears, flowing manes, and bushy tails. The word for "horse" in Sumerian, meaning "ass of the mountains," first appeared around 2100–2000 BCE. Kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur fed horses to lions, perhaps showing horses were still seen as exotic. But King Shulgi (around 2050 BCE) compared himself to a "horse of the highway." One image from his time shows a man riding a horse at full speed. More horses were brought into Mesopotamia after 2000 BCE for chariot warfare. They replaced the kunga (a hybrid animal) as the main animal for war.

Horses also spread to the lowland Near East and northwestern China around 2000 BCE. Horse bones appeared in many sites of the Qijia and Siba cultures (2000–1600 BCE) in China. Bones from sites in Xinjiang show that by the 4th century BCE, people were both riding horses and shooting arrows from horseback on China’s northwest border.

In 2008, archaeologists found rock art in Somalia. It shows a hunter on horseback and is thought to be one of the earliest pictures of this. It dates to 1000 to 3000 BCE.

Horses as Symbols of Power

Around 4200-4000 BCE, new types of graves appeared in Ukraine. These "Suvorovo" graves were similar to older traditions. Some Suvorovo graves had polished stone mace-heads shaped like horse heads and horse tooth beads. Earlier graves also had animal-shaped mace-heads. Settlements from this time had many horse bones (12–52%).

When Suvorovo graves appeared, horse-head maces also showed up in farming towns in Romania and Moldova. These farming cultures had not used such maces before, and horse bones were rare in their sites. This suggests the horse-head maces came from the Suvorovo people. After this contact, many farming towns in the Balkans were abandoned. Copper mining stopped, and old cultural traditions ended. This collapse has been linked to the arrival of mounted warriors. Warfare might have increased due to mounted raids, and the horse-head maces might show that domesticated horses and riding were introduced just before this collapse.

However, mounted raiding is just one idea. Environmental problems, damage from thousands of years of farming, and running out of easily mined copper might also have caused the collapse.

Artifacts and Tools

Some perforated antler objects found at Dereivka were once thought to be cheekpieces for horse bits. This idea is not widely accepted now. These objects were not found with horse bones and could have had other uses. However, studies show that many bone tools at Botai were used to smooth rawhide strips. These strips might have been used to make rawhide cords and ropes, useful for horse tack.

The oldest tools clearly identified as horse tack are the antler disk-shaped cheekpieces. These were found with the invention of the chariot at the Sintashta-Petrovka sites.

Horses Buried in Human Graves

The oldest possible sign of a changed relationship between horses and humans is the appearance of horse bones and carved horse images in graves. This happened around 4800–4400 BCE in the early Khvalynsk culture and Samara culture in Russia. At the Khvalynsk cemetery, 26 out of 158 graves had parts of sacrificed domestic animals. Ten graves had parts of horse legs. At least 11 horses were sacrificed there, along with sheep and cattle. Including horses with cattle and sheep, and not with wild animals, suggests horses were seen as domesticated.

At S'yezzhe, another cemetery from the same time, parts of two horses were placed above human graves. Only the head and hooves were there, likely still attached to hides. This same ritual was used for many sacrificed cattle and sheep at Khvalynsk. Horse images carved from bone were also found. These clues suggest horses had a special meaning in these cultures. They were linked to humans and other domestic animals. So, the earliest stage of horse domestication might have begun around 4800-4400 BCE.

How Horses Were Tamed

Horse-like animals died out in the Western Hemisphere at the end of the last glacial period. A question is why horses survived in Eurasia. Some think domestication saved the species. While conditions were better for horses in Eurasia, the same problems that led to the extinction of the mammoth also affected horse populations. So, after 8000 BCE, humans in Eurasia might have started keeping horses for food. By keeping them captive, they might have helped the species survive. Horses also fit the criteria for being tamed.

One idea is that domestication started with individual foals being kept as pets. The adult horses were killed for meat. Foals are small and easy to handle. Horses are herd animals and need company. Both old and new information shows that foals can bond with humans and other animals. So, domestication might have begun with young horses becoming pets over time. Later, people discovered these pets could be ridden or put to work.

However, there's disagreement about what "domestication" means. Some say it must include physical changes from being bred in captivity, not just being "tamed." People worldwide often tame wild animals, usually by raising babies whose parents were killed. But these animals are not always "domesticated."

Others look at historical examples. For instance, Native American cultures captured and rode horses from the 16th century onwards. Most tribes didn't control their breeding much. So, their horses developed traits suited to their uses and climate. These horses were more like a natural type than a planned breed, but they were still "domesticated."

Riding or Driving First?

It's a tough question whether horses were first ridden or driven (pulling something). The clearest proof shows horses first pulling chariots in wars. But there's strong, indirect evidence that riding came first, especially with the Botai people. Bit wear might mean riding. However, horses can be ridden without a bit, using simple ropes or blankets. These materials don't last, so it's hard to find proof of early riding.

Logically, horses would have been ridden long before they were driven. But it's much harder to find proof of riding. Simple riding gear like hackamores or blankets wouldn't survive as artifacts. Besides bit wear, riding wouldn't necessarily cause big changes in a horse's bones. Direct evidence of horses being driven is much stronger.

Horses in Ancient Wars

While riding might have happened between 4000 and 2000 BCE, horses clearly influenced ancient warfare by pulling chariots. Chariots were introduced around 2000 BCE.

Horses in the Bronze Age were smaller than modern horses. Some thought this meant they were too small to be ridden and only used for pulling. But horses remained smaller than modern ones even into the Middle Ages. Small horses were successfully used as light cavalry for many centuries. For example, Fell ponies, thought to be from Roman cavalry horses, are about 13.2 hands high. They can easily carry adults. The Arabian horse is also known for its short back and strong bones. The success of Muslim warriors against heavy European knights showed that a 14.2-hand horse could easily carry an adult into battle.

Mounted warriors like the Scythians, Huns, and Vandals in late Roman times, and the Turks and Mongols who invaded Europe, showed how effective light cavalry could be. Arab warriors and Native Americans also used effective forms of light cavalry.

See also

- Anthrozoology

- Equestrian nomad

- List of horse breeds

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |