Erik Adolf von Willebrand facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Erik Adolf von Willebrand

|

|

|---|---|

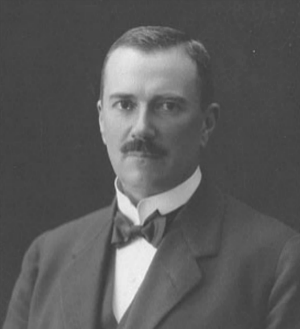

Erik Adolf von Willebrand, c. 1915

|

|

| Born | 1 February 1870 |

| Died | September 12, 1949 (aged 79) Pernå, Finland

|

| Education | University of Helsinki |

| Known for |

|

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Physician |

| Institutions |

|

| Research | Hematology, thermotherapy, phototheraphy, metabolism, obesity, gout |

| Notable works | Hereditär pseudohemofili (1926) |

Erik Adolf von Willebrand (born February 1, 1870 – died September 12, 1949) was a Finnish doctor. He made very important discoveries in the study of blood, known as hematology. Two key medical terms, Von Willebrand disease and von Willebrand factor, are named after him.

He also studied how our bodies use food for energy (metabolism), being overweight (obesity), and a type of arthritis called gout. Dr. von Willebrand was also one of the first doctors in Finland to use insulin to help people in a diabetic coma.

He became a doctor in 1896 after studying at the University of Helsinki. He earned his Ph.D. there in 1899. Dr. von Willebrand worked at the University of Helsinki from 1900 to 1930. From 1908 until he retired in 1933, he led the medicine department at the Deaconess Hospital in Helsinki. He was also the chief doctor there from 1922 to 1931.

In 1924, a young girl with a serious bleeding problem came to him. He described this problem in 1926. He showed it was different from hemophilia, another bleeding disorder. This new condition was later named von Willebrand disease. Years later, scientists found that a missing protein, now called von Willebrand factor, caused the disease. This protein helps blood to clot and stop bleeding.

Contents

Who Was Erik von Willebrand?

Erik von Willebrand was born on February 1, 1870. His birthplace was Nikolainkaupunki, which is now Vaasa, in what was then the Grand Duchy of Finland. At that time, Finland was part of the Russian Empire. He was the third child of Fredrik Magnus von Willebrand and Signe Estlander. His family had German roots and had moved to Finland in the 1700s. They were part of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland.

His School Days and Early Interests

Erik went to Vaasa Lyceum for school. He was very good at subjects like botany (the study of plants), chemistry, and zoology (the study of animals). During his summers, he loved collecting plants, butterflies, and birds. In winter, he explored the Gulf of Bothnia. After finishing school in 1890, he started studying at the University of Helsinki.

Before becoming a doctor in 1896, he worked as a junior doctor at a spa in Åland during the summers of 1894 and 1895. After graduating, he became an assistant doctor at the Deaconess Hospital in Helsinki. There, he studied how blood cells change after blood is taken from the body. He also studied how blood regenerates after anemia and found a new way to stain blood smears for better viewing. He earned his Ph.D. in 1899.

Dr. von Willebrand's Medical Career

After finishing his Ph.D. in 1899, Dr. von Willebrand became the chief doctor at a spa in Heinola. He then became more interested in how the body works (applied physiology). From 1900 to 1906, he taught anatomy and later physiology at the University of Helsinki. During this time, he researched thermotherapy (treatment using heat), especially the health benefits of saunas. He also studied phototherapy (treatment using light). He even invented a device to measure how much carbon dioxide and water the skin releases.

Focus on Internal Medicine

Dr. von Willebrand became more interested in internal medicine, which deals with diseases of the internal organs. In 1907, he became chief doctor at a city hospital in Helsinki. In 1908, he started teaching internal medicine at the University of Helsinki. At the same time, he took over as head of the medicine department at the Deaconess Hospital. This hospital was well-known for its blood-related services.

In this new role, he studied metabolism, obesity, and gout. In 1912, he created a way to measure certain chemicals in urine. The next year, he talked about how diet could help treat diabetes. He also published studies on different types of anemia. He even studied heart valve conditions using information from over 10,000 autopsies.

Dr. von Willebrand was also a pioneer in using insulin. In 1922, he described how to use it to treat diabetic comas. In February 1924, he successfully saved a patient from a diabetic coma using insulin. This was one of the first times insulin was used in Finland.

He stayed at the University of Helsinki until 1930. He was the chief doctor of the Deaconess Hospital from 1922 to 1931. He became an honorary professor in 1930. He continued to lead the Deaconess Hospital's medicine department until he retired in 1933. Even after retiring, Dr. von Willebrand kept writing articles. On his 75th birthday, he published his last paper about a genetic blood disease found in the people of Åland.

Discovering Von Willebrand Disease

In April 1924, Dr. von Willebrand met Hjördis Sundblom, a five-year-old girl with a severe bleeding problem. Hjördis was one of 11 children from a family on Föglö, one of the Åland Islands. She often had bleeding from her nose, lips, gums, and skin. Six of her siblings also had this problem. Three of her sisters had died because of it. Eight years later, Hjördis also died from heavy bleeding during her period.

Dr. von Willebrand studied Hjördis's family history. He found that the bleeding condition was present in three previous generations on both sides of her family. He saw that 16 of 35 women had the condition (mild or severe), and 7 of 31 men had it (mild). He realized that this condition was passed down in a dominant way. This was different from hemophilia, which is a recessive disorder and mostly affects males. Also, this new condition affected females as often as males, unlike hemophilia.

In 1926, he published an article in Swedish about the disease. He called it Hereditär pseudohemofili, meaning "Hereditary pseudohemophilia." He explained that it was different from other known bleeding disorders. He also did blood tests on Hjördis and her family. He found that their platelet count was normal or slightly low, and their blood clotted well. However, their bleeding time (how long it takes for a small cut to stop bleeding) was very long, sometimes over two hours. He thought the disease might be a new type of blood problem or a condition of the small blood vessels.

In 1931, Dr. von Willebrand published a German version of his article. This brought international attention to the disease. Blood samples were sent to researchers in the United States and Europe. One researcher, Rudolf Jürgens, worked with Dr. von Willebrand. Together, they studied his patients and the causes of bleeding disorders. In 1933, they wrote a paper together, renaming the disease "constitutional thrombopathy." Many more papers were published, and by the early 1940s, it became known as von Willebrand disease.

In 1957, scientists discovered that von Willebrand disease is caused by a lack of a protein in the blood plasma. This protein helps blood to clot. In 1971, this protein was fully described and named von Willebrand factor. This factor has two main jobs: it carries another important clotting factor (factor VIII), and it helps platelets stick together and to the blood vessel walls to stop bleeding.

His Life and Legacy

People described Dr. von Willebrand as a kind and humble man. He married Walborg Maria Antell in 1900, and they had two daughters. As a member of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland, he supported an organization called Folkhälsan. This group helped improve social welfare and health care for Swedish-speaking Finns. His research on the bleeding condition in the Åland islanders was especially important to him because it affected this minority group. After he retired in 1933, he became a keen gardener and supported nature conservation.

Erik von Willebrand passed away on September 12, 1949, at the age of 79. In 1994, Åland honored him with a special postage stamp. This stamp was part of a set of two; the other honored Erik Jorpes, who was known for his work on heparin, another important blood-related discovery.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |