Ernst von Weizsäcker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ernst von Weizsäcker

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Secretary of State at the Foreign Office Germany |

|

| In office 1938–1943 |

|

| Preceded by | Hans Georg von Mackensen |

| Succeeded by | Gustav Adolf Steengracht von Moyland |

| Ambassador to the Holy See Germany |

|

| In office 1943–1945 |

|

| Preceded by | Diego von Bergen |

| Succeeded by | Wolfgang Jaenicke (1954) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 May 1882 Stuttgart, German Empire |

| Died | 4 August 1951 (aged 69) Lindau, West Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1900–1920, 1938–1945 |

| Rank | SS-Brigadeführer Korvettenkapitän |

| Battles/wars | First World War Second World War |

| Awards | Iron Cross (1st class) Iron Cross (2nd class) |

Ernst Heinrich Freiherr von Weizsäcker (born May 25, 1882 – died August 4, 1951) was a German naval officer, diplomat, and politician. He held important roles in Germany's government. From 1938 to 1943, he was the State Secretary at the German Foreign Office. This was the second-highest position in the foreign ministry. Later, from 1943 to 1945, he served as Germany's Ambassador to the Holy See (the government of the Catholic Church). Ernst von Weizsäcker was part of the well-known Weizsäcker family. His son, Richard von Weizsäcker, later became the President of Germany.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Ernst von Weizsäcker was born in 1882 in Stuttgart, Germany. His father, Karl Hugo von Weizsäcker, became the prime minister of the Kingdom of Württemberg. In 1911, Ernst married Marianne von Graevenitz. In 1916, his family was given the noble title of Freiherr, which means Baron.

In 1900, Ernst von Weizsäcker joined the Imperial German Navy to become an officer. He served in Berlin for most of his naval career. In 1916, during the First World War, he was an officer on the German flagship SMS Friedrich der Grosse during the Battle of Jutland. This was a major naval battle.

In 1917, he received the Iron Cross, a military award, for his service. The next year, he was promoted to Korvettenkapitän, a rank similar to a lieutenant commander in other navies. From 1919 to 1920, he worked as a naval attaché in The Hague, a city in the Netherlands.

Diplomatic Service

After his naval career, Weizsäcker joined the German Foreign Service in 1920. He worked in several important diplomatic roles. He was a Consul in Basel, Switzerland, in 1921. Later, he was a Councillor in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1924. He also worked in Geneva, Switzerland, from 1927.

In 1928, he became the head of the department for disarmament. This department worked on reducing military weapons. He then served as an envoy (a type of diplomat) in Oslo, Norway, in 1931, and in Bern, Switzerland, in 1933.

In 1936, while in Bern, Weizsäcker played a part in removing German citizenship from the famous writer Thomas Mann. In 1937, he became the Director of the Policy Department at the Foreign Office. The next year, he was appointed Staatssekretär (State Secretary). This was the second-highest position in the German Foreign Office, after the Foreign Minister.

In 1938, Weizsäcker joined the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP). He also received an honorary rank in the Schutzstaffel (SS). During this time, he disagreed with the idea of attacking Czechoslovakia. He was worried that such an attack could start a big war that Germany might lose. He was not against the idea of controlling Czechoslovakia, but he thought the timing was wrong.

Weizsäcker had some contact with people who opposed the government. However, he only claimed to be a strong anti-Nazi working against the regime after he was put on trial after the war.

In 1938, Weizsäcker wrote a memo to the Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop. In it, he said that Germany should wait for England to lose interest in Czechoslovakia before taking action without risk. Weizsäcker, along with other officials like Admiral Wilhelm Canaris and General Ludwig Beck, wanted to avoid a war in 1938. They believed Germany would lose such a war.

Historian Eckart Conze explained in 2010 that this group did not want to overthrow Hitler. Instead, they wanted to prevent a major war and its terrible consequences for Germany. Their goal was to make Hitler see reason, not to remove him from power. Weizsäcker was promoted to SS-Brigadeführer in 1942.

Ambassador to the Vatican

After Germany's defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad in 1943, the war situation changed. Weizsäcker asked to resign as State Secretary. He was then appointed as the German Ambassador to the Holy See (Vatican City) from 1943 to 1945.

When he met with Cardinal Secretary of State Luigi Maglione in 1944, Weizsäcker said that if Germany fell, all of Europe might become communist. Cardinal Maglione replied that it was a shame Germany's anti-religious policies had caused such worries. Weizsäcker made similar statements to Monsignore Giovanni Battista Montini, who later became Pope Paul VI.

Weizsäcker's actions at the Vatican were complex. He did not accept a papal note protesting the treatment of people in occupied Poland. During the German occupation of Rome, he did little to stop the deportation of Jewish people. However, he did help some individuals avoid persecution. He also tried to remove German military bases from Rome to prevent Allied bombing of the city. He suggested to the Foreign Office that sending Jewish people to labor camps in Italy would cause less protest from the Pope than deporting them from Italy.

His colleague, Albrecht von Kessel, later said that Weizsäcker's messages to Berlin were "nothing but lies." In these messages, Weizsäcker described Pope Pius XII as mild and pro-German. He did this to help the Pope and prevent anti-German feelings in Italy. Weizsäcker also opposed Hitler's plan to occupy the Vatican. He feared the Pope might be harmed if this happened.

Weizsäcker continued to use anti-communist arguments with the Vatican. He also asked for the Pope to start a peace effort to end the war in the West. This would allow Germany to focus on fighting communism in the East. However, this was seen as an attempt to gain a military advantage.

Like other German officials, Weizsäcker tried to negotiate for some part of the German government to survive. He wanted to avoid Germany's unconditional surrender. However, his efforts to discuss a "German transition government" failed.

After the War

After the war ended, Weizsäcker and his wife stayed in Vatican City as guests of the Pope. He did not return to Germany until 1946. On July 25, 1947, Weizsäcker was arrested in Nuremberg. He was put on trial in the Ministries Trial, also known as the Wilhelmstrasse Trial. This trial was held by American military tribunals in Germany.

Weizsäcker's supporters argued that he had been connected to the anti-Nazi resistance. They said he was a moderate force in the Foreign Office during the war.

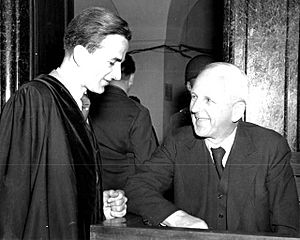

Weizsäcker was accused of helping with the deportation of French Jews to Auschwitz. This was considered a crime against humanity. Weizsäcker, with help from his son Richard von Weizsäcker (who was a law student and helped with his defense), claimed he did not know what Auschwitz was used for. He said he believed Jewish prisoners would be safer if they were sent to the East.

In 1949, Weizsäcker was found guilty of crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. He was sentenced to 7 years in prison. Winston Churchill called his sentence a "deadly error." Later that year, his sentence was reduced to 5 years, after the conviction for crimes against peace was overturned. In October 1950, he was released early from Landsberg Prison after serving 3 years and 3 months. This decision was made by John J. McCloy, the US High Commissioner for Germany. After his release, Weizsäcker published his memoirs, which he wrote in prison. In these memoirs, he presented himself as a supporter of the German Resistance.

Death and Legacy

Ernst von Weizsäcker died on August 4, 1951, at the age of 69, due to a stroke.

In 2010, historian Eckart Conze discussed the idea that the German Federal Foreign Office had no involvement in war crimes. He explained that this idea came from people connected to Weizsäcker's defense. These included former diplomats and other members of the traditional upper class that Weizsäcker represented. Conze stated that if they could clear Weizsäcker's name, they would also help to restore the reputation of the national conservative, aristocratic, and middle-class elite.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ernst von Weizsäcker para niños

In Spanish: Ernst von Weizsäcker para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |