Evelyn Underhill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Evelyn Underhill

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 6 December 1875 Wolverhampton, England |

| Died | 15 June 1941 (aged 65) London, England |

| Occupation | Novelist, writer, mystic |

| Genre | Christian mysticism, spirituality |

| Notable works | Mysticism |

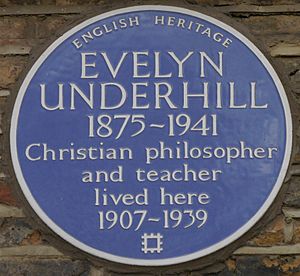

Evelyn Underhill (born December 6, 1875 – died June 15, 1941) was an English writer. She was known for her many books about religion and spiritual life, especially Christian mysticism. Her most famous book is Mysticism, which came out in 1911. She was also a pacifist, meaning she believed in peace and was against war.

Contents

Evelyn Underhill's Life

Evelyn Underhill was born in Wolverhampton, England. She was a poet and wrote novels, as well as being a pacifist and a mystic. A mystic is someone who tries to find a deeper connection with God or a spiritual reality.

Evelyn was an only child. She once described her early spiritual experiences as "peaceful" moments where everything felt connected and simple. Understanding these moments became a big part of her life and led her to research and write.

Her father, Arthur Underhill, and her husband, Hubert Stuart Moore, were both lawyers and writers. They also enjoyed sailing. Evelyn and Hubert grew up together and got married on July 3, 1907. They did not have any children.

Evelyn often traveled around Europe, visiting places like Switzerland, France, and Italy. She loved art and learning about Catholicism, visiting many churches and monasteries. Her husband and parents did not share her strong interest in spiritual topics.

Many of her friends called her "Mrs. Moore." She wrote a lot, publishing over 30 books. Some were under her maiden name, Underhill, and some under a pen name, "John Cordelier."

At first, Evelyn was an agnostic, meaning she wasn't sure if God existed. But she slowly became interested in Neoplatonism, a type of philosophy. From there, she became more and more drawn to the Catholic Church. Her husband didn't agree with this, but she eventually became a prominent Anglo-Catholic. This is a group within the Anglican Church that has many Catholic traditions.

From 1921 to 1924, her spiritual guide was Baron Friedrich von Hügel. He liked her writing but encouraged her to focus more on Jesus, rather than just on general spiritual ideas. She said he was "wonderful" and "saintly." After he died in 1925, her writings focused more on the Holy Spirit. She became an important leader in the Anglican Church. She led spiritual retreats, guided many people, gave talks on the radio, and promoted quiet prayer.

Evelyn grew up during the Edwardian era, around the early 1900s. This was a time when many people were excited about new ideas in science, art, and spirituality. Evelyn felt that the traditional church didn't quite fit with this new way of thinking. She looked for the center of life in personal experience and the heart, rather than just in formal religion.

She was very close to her parents and, later, to her husband. She lived a busy life as a lawyer's daughter and wife, which included entertaining guests and doing charity work. Every day, she made time for writing, research, worship, prayer, and meditation. She believed that all parts of life were sacred.

Evelyn was also a cousin of Francis Underhill, who became a Bishop.

Evelyn Underhill's Education

Evelyn Underhill was mostly taught at home. She spent three years at a private school in Folkestone. Later, she studied history and botany at King's College London.

She received an honorary degree called a Doctorate of Divinity from Aberdeen University. She was also made a fellow of King's College. Evelyn was the first woman to give lectures to church leaders in the Church of England. She was also the first woman to officially lead spiritual retreats for the Church. She helped create connections between different churches and was one of the first women theologians to lecture in English colleges and universities.

Evelyn was also an award-winning bookbinder. She learned from the best masters of her time. She knew a lot about classic literature, Western spirituality, philosophy, psychology, and physics. She also wrote and reviewed books for The Spectator magazine.

Evelyn Underhill's Early Work

Before writing her famous books on mysticism, Evelyn published a small book of funny poems about legal problems called The Bar-Lamb's Ballad Book. People liked it.

Then, she wrote three unique novels that explored deep spiritual ideas. Like other writers, she used her stories to show how the physical world and the spiritual world connect. Her novels were The Grey World (1904), The Lost Word (1907), and The Column of Dust (1909).

In her first novel, The Grey World, the main character's spiritual journey begins with death and moves through different experiences. It ends with a choice to live a simple life focused on beauty. This reflected Evelyn's own serious thoughts as a young woman.

The Lost Word and The Column of Dust also deal with the challenge of living in two worlds. They show the spiritual struggles the writer herself faced. Evelyn's novels suggest that for a mystic, having two worlds might be better than one. For her, mystical experiences seemed to make people more aware and see things in a new light. Things that seemed small and unimportant could appear grand and shining when seen with a spiritual view.

However, these early stages can also bring fear and insecurity. Later stages of spiritual growth, according to Evelyn, require suffering. This is because mysticism is more than just seeing visions. It involves letting go of one's self-centered life to find one's true self. Her later novels explore this idea of giving up everything, even the vision itself, to fully connect with life. This was her way of showing the deeper meaning of Jesus' life story.

Her characters are interesting because they represent theological ideas. Her clever way of handling these symbolic ideas makes her work psychologically interesting. Her first novel was praised, but her last one was not as well received. Still, her novels give us a great look into her decision to embrace this world with love, rather than escaping into solitude. After these novels, she began working on her most important book.

Evelyn Underhill's Writings on Religion

- Mysticism (1911)

- Ruysbroeck (1914)

- The Mysticism of Plotinus (1919)

- Worship (1936)

Evelyn Underhill's Influences

Evelyn Underhill's life was greatly affected by her husband's wishes. He did not want her to join the Catholic Church, even though she felt strongly drawn to it. This meant she never officially joined, though she wanted to. Her husband was a writer too and supported her writing, even if he didn't share her spiritual interests.

Her novels were written between 1903 and 1909. They show her main interests during that time: philosophy (like Neoplatonism), spiritual beliefs, Catholic traditions, and human love. In her earlier writings, she often used the words "mysticism" and "mystics." Later, she started using "spirituality" and "saints" because she felt they sounded less scary. She was often criticized for believing that anyone could have a mystical life, not just special people.

Two important philosophers, Rudolf Eucken and Henri Bergson, influenced Evelyn's thinking when she wrote "Mysticism." While they weren't focused on mysticism, their ideas seemed to offer a spiritual explanation for the universe. She felt they confirmed what mystics had always known.

Among the mystics, Ruysbroeck was the most important to her. She felt a strong connection to him.

One of her most important collaborations was with Rabindranath Tagore. He was an Indian mystic, writer, and Nobel Prize winner. In 1915, they worked together to publish a major translation of the work of Kabir, called 100 Poems of Kabir (also known as Songs of Kabir). Evelyn wrote the introduction.

They didn't stay in touch in later years. Both suffered from serious illnesses in their last year of life and died in the summer of 1941. They were very upset by the start of World War II.

By 1921, Evelyn seemed to be in a very good place. Oxford University had asked her to give the first in a new series of lectures on religion. She was the first woman to receive such an honor. She was an expert on mysticism and respected for her research. Her writing was popular, and she had many interesting friends, devoted readers, a happy marriage, and loving parents. Yet, she still felt a bit unsure about her spiritual path.

By 1939, she had joined the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship. She wrote several important papers expressing her feelings against war.

After becoming an Anglican, and perhaps feeling overwhelmed by the great achievements of mystics, her friendship with Catholic philosopher Baron Friedrich von Hügel turned into a spiritual guidance relationship. She wanted to be "sure" about her faith.

Even though Evelyn continued to struggle with doubts, she played a powerful role in helping her country during World War II. She was a pacifist and deeply distressed by the war. She survived the London Blitz bombings in 1940, but her health got worse. She died the following year. She is buried with her husband in the churchyard at St John-at-Hampstead in London.

More than anyone else, Evelyn Underhill helped introduce forgotten medieval and Catholic spiritual writers to a mostly Protestant audience. She also introduced the lives of Eastern mystics to the English-speaking world. She was often a guest on the radio. Her 1936 book The Spiritual Life was very influential. It was based on a series of radio talks she gave about prayer.

When she died, The Times newspaper said that when it came to theology, she was "unmatched by any of the professional teachers of her day."

Veneration

Evelyn Underhill is honored on June 15th in the calendars of several Anglican churches. These include churches in Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, England, the United States, and North America.

See also