John of the Cross facts for kids

Quick facts for kids SaintJohn of the Cross OCD |

|

|---|---|

Saint John of the Cross,

17th century anonymous |

|

| Priest, Mystic, Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | Juan de Yepes y Álvarez 24 June 1542 Fontiveros, Ávila, Crown of Castile, Spanish monarchy |

| Died | 14 December 1591 (age 49) Úbeda, Kingdom of Jaén, Crown of Castile, Spanish monarchy |

| Venerated in | |

| Beatified | 25 January 1675, Rome by Pope Clement X |

| Canonized | 27 December 1726, Rome by Pope Benedict XIII |

| Major shrine | Tomb of Saint John of the Cross, Segovia, Spain |

| Feast | 14 December |

| Attributes | Carmelite habit, cross, crucifix, book, quill |

| Patronage | Spanish poets |

| Influences | Likely Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, Guillaume Durand, Teresa of Ávila Possibly Pseudo-Dionysius, Meister Eckhart, John of Ruysbroeck, Henry Suso, Johannes Tauler |

| Influenced | |

| Major works |

|

Saint John of the Cross (born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez; June 24, 1542 – December 14, 1591) was a Spanish Catholic priest and a Carmelite friar. He is known for his important writings on mystical experiences.

John of the Cross worked closely with Teresa of Ávila to reform the Carmelite Order. His poems and writings about the journey of the soul are considered some of the best works in Spanish literature. He was made a saint by Pope Benedict XIII in 1726. Later, in 1926, Pope Pius XI declared him a "Doctor of the Church," which means his teachings are very important to the Catholic faith.

Contents

Life Story

Early Years and School

John was born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez in Fontiveros, Spain. His family had a Jewish background but had converted to Catholicism. His father, Gonzalo, worked for richer relatives who were silk merchants. However, when Gonzalo married John's mother, Catalina, who was from a poorer family, his own family rejected him. This meant John's parents had to work as weavers.

John's father died when John was only three years old. A few years later, his older brother, Luis, also died, likely because the family was very poor and didn't have enough food. Because of this, John's mother moved with John and his other brother, Francisco, to find work. They first went to Arévalo and then to Medina del Campo.

In Medina, John went to a school for poor children, many of whom were orphans. He learned basic Christian teachings and was given food, clothes, and a place to stay. He also served as an altar boy at a nearby monastery. As he grew up, John worked at a hospital and studied at a Jesuit school from 1559 to 1563. The Jesuits were a new religious group founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola. In 1563, John joined the Carmelite Order and took the name John of St. Matthias.

The next year, in 1564, he officially became a Carmelite. He then went to Salamanca University to study theology and philosophy. There, he met Luis Ponce de León, a professor who taught about the Bible.

Joining Teresa of Ávila's Reform

John became a priest in 1567. He thought about joining a very strict order called the Carthusians, who lived in silence and solitude. However, in September 1567, he met the famous Carmelite nun, Teresa of Ávila, in Medina. Teresa was working to reform the Carmelite Order. She wanted to go back to the original, stricter rules from 1209.

These old rules meant spending much of the day in prayer, study, and silence. Friars also had to preach to people. They were not allowed to eat meat and had to fast for a long time each year. They also wore simpler, shorter clothes and did not wear covered shoes. This practice of not wearing shoes led to them being called "discalced" (meaning "barefoot"). This group later became known as the separate Order of Discalced Carmelites in 1580.

Teresa asked John to join her reform instead of the Carthusians. After another year of study, John joined Teresa in August 1568. He learned about her new way of Carmelite life. In October 1568, John and another friar, Antonio de Jesús de Heredia, started the first monastery for Carmelite friars following Teresa's rules. It was in a small, old house in Duruelo. On November 28, 1568, the monastery was officially opened, and John changed his name to "John of the Cross."

Soon, the house in Duruelo became too small. The friars moved to Mancera de Abajo in June 1570. John then helped start new communities in Pastrana and Alcalá de Henares. The Alcalá community was a training house for new friars. In 1572, Teresa invited John to Ávila, where she was in charge of a convent. John became the spiritual guide for Teresa and the 130 nuns there, as well as for many other people in the city. He stayed in Ávila from 1572 to 1577, except for one trip with Teresa to Segovia in 1574.

Between 1574 and 1577, while praying in Ávila, John had a vision of Jesus Christ on the cross. This vision inspired him to draw a picture of Christ "from above." This drawing was later kept in Ávila and even inspired the famous artist Salvador Dalí's painting Christ of Saint John of the Cross in 1951.

Challenges and Imprisonment

From 1575 to 1577, there was a lot of tension among Carmelite friars in Spain. Some friars did not like the reforms that Teresa and John were trying to make. Church leaders from the Dominican Order were overseeing these reforms. In Castile, the leader, Pedro Fernández, tried to keep peace between the different groups.

However, in Andalusia, another leader, Francisco Vargas, strongly favored the Discalced friars. He encouraged them to start new monasteries, even though the head of the Carmelite Order had told them to slow down. Because of this, a big meeting of the Carmelite Order was held in Italy in May 1576. They decided to stop all the Discalced houses.

This order was not immediately put into action. King Philip II of Spain supported Teresa's reforms, so he didn't allow the order to be enforced right away. The Discalced friars also got help from the Pope's representative in Spain, Nicolò Ormaneto. Ormaneto had the power to reform religious orders. He replaced Vargas with Jerónimo Gracián, who was a Discalced Carmelite himself. This protection helped John for a while. In January 1576, John was briefly held by traditional Carmelite friars but was released thanks to Ormaneto.

However, when Ormaneto died in June 1577, John lost his protection. The friars who opposed the reforms gained power. On December 2, 1577, John was captured by these friars in Ávila. He was taken to a monastery in Toledo and imprisoned in a small, dark cell. He was kept there for nine months and was treated very harshly. During this difficult time, John wrote some of his most famous poems, including the first 31 stanzas of his Spiritual Canticle and parts of Dark Night of the Soul.

On August 15, 1578, John managed to escape from his prison. He broke a window, climbed down a rope, and found shelter with Discalced nuns.

Becoming a Saint

After John's death in Úbeda, many townspeople came to see his body. They were so eager that some even took pieces of his habit as souvenirs. He was first buried in Úbeda. However, the monastery in Segovia wanted his body, so it was secretly moved there in 1593. The people of Úbeda were upset and asked the Pope to return the body.

As a compromise, the Carmelite leaders decided that Úbeda would receive one leg and one arm of the body from Segovia. (Úbeda had already kept one leg in 1593, and another arm was taken in Madrid in 1593 to become a relic there). Today, a hand and a leg can still be seen in a special display at the Oratory of San Juan de la Cruz in Úbeda.

The head and torso remained in Segovia. They were honored until 1647, when church rules changed to prevent honoring remains without official approval. The remains were then buried. In the 1930s, they were dug up again and are now in a special marble case in a chapel in Segovia.

The process to declare John a saint began between 1614 and 1616. He was officially declared "blessed" (beatified) in 1675 by Pope Clement X. He was then made a saint (canonized) by Pope Benedict XIII in 1726. His feast day, which is a special day to remember him, is celebrated on December 14. This is the day he died. The Church of England and the Episcopal Church also honor him on this date. In 1926, Pope Pius XI declared him a "Doctor of the Church."

His Writings

John of the Cross is considered one of the greatest poets in Spanish history. Even though his complete poems are less than 2,500 lines long, two of them, the Spiritual Canticle and the Dark Night of the Soul, are seen as masterpieces. They are admired for their beautiful style and deep meaning. His other writings are often explanations of these poems. All his works were written between 1578 and his death in 1591.

The Spiritual Canticle is a poem about the soul's search for Jesus Christ. The soul is like a bride looking for her groom. They are both very happy when they finally reunite. This poem is like a Spanish version of the Song of Songs from the Bible. John wrote the first 31 stanzas while he was in prison in Toledo in 1578. After he escaped, he added more lines. Today, there are two versions of the poem, one with 39 stanzas and one with 40. He also wrote a detailed explanation of the poem in 1584 and 1585–86.

The Dark Night poem describes the soul's journey to unite with God. The "dark" part means the difficulties and challenges the soul faces when it tries to let go of worldly things to reach God's light. The poem explains different stages of this "darkness." The main idea is that it takes a painful experience to grow spiritually and become one with God. This poem was likely written in 1578 or 1579. John wrote an explanation for the first part of the poem in 1584–85.

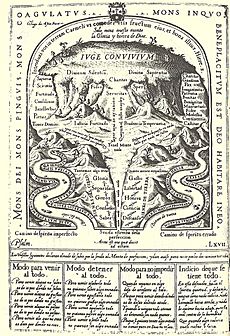

The Ascent of Mount Carmel is a more detailed study of how a soul tries to achieve perfect union with God. It also talks about the mystical experiences that happen along the way. This work started as a commentary on The Dark Night but quickly became its own complete book. He wrote it between 1581 and 1585.

Another work, Living Flame of Love, has four stanzas. It describes a deeper connection between the soul and God, where the soul responds to God's love. He wrote the first version in Granada between 1585 and 1586 and a second version in 1591.

These works, along with his "Sayings of Light and Love," are among the most important mystical writings in Spanish. They have greatly influenced many spiritual writers around the world, including T. S. Eliot, Thérèse de Lisieux, Edith Stein, and Thomas Merton. John also influenced philosophers, theologians, pacifists, and artists like Salvador Dalí. Pope John Paul II even wrote his advanced degree paper on John of the Cross's mystical ideas.

How His Works Were Published

John's writings were first published in 1618 by Diego de Salablanca. The numbers used to divide the sections in modern books of his works were added by Salablanca to make them easier to read. This first edition did not include the Spiritual Canticle and left out or changed some parts, possibly to avoid problems with the Inquisition (a church court).

The Spiritual Canticle was first included in the 1630 edition, published in Madrid. Later editions in the 17th and 18th centuries gradually added more of his poems and letters.

The first French edition was published in Paris in 1622, and the first Spanish edition outside of Spain was published in Brussels in 1627. A very important English edition of his works was published by Edgar Allison Peers in 1935.

Influences on His Writing

Many different ideas and writings influenced John of the Cross. At Salamanca University, where John studied, there were many different ways of thinking. These included the ideas of Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, and Guillaume Durand. It is often thought that John learned from Aquinas, which explains the organized way his writings are structured.

However, some experts question whether John actually studied theology at Salamanca University. They suggest he might have left his studies early in 1568 to join Teresa. The first book about John's life, published in 1628, says that he specifically studied mystical writers in 1567, especially Pseudo-Dionysius and Pope Gregory I.

The Bible

The Bible had a huge influence on John's writing. Images and stories from the Bible appear often in his poems and other works. He used over 1,500 direct quotes and many more indirect references from the Bible in his writings. The Song of Songs from the Bible especially influenced his Spiritual Canticle. Both works use a dialogue between two lovers, describe their difficulties in meeting, and have a "chorus" that comments on the story. They also use similar images like pomegranates, wine cellars, and lilies.

John also used phrases and language from the Liturgy of the Hours, which are daily prayers in the Church. This shows how deeply he was connected to the Church's language and rituals.

Other Mystics

It is believed that John was influenced by other medieval mystics, though it's not always clear exactly which ones or how he learned about their ideas. Many authors suggest he might have been influenced by the "Rhineland mystics" like Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Henry Suso, and John of Ruysbroeck.

Spanish Poetry

John was also strongly influenced by Spanish poetry of his time. Some experts believe he took non-religious themes from popular Spanish songs (romanceros) and changed them into religious poetry.

Islamic Influence

One interesting idea is that John's mystical images might have been influenced by Islamic sources. This idea was first suggested by Miguel Asín Palacios and more recently by Luce López-Baralt. She argues that John was influenced by Islamic ideas from Spain, pointing to similarities in images like the "dark night," the "solitary bird," and "lamps of fire." However, other experts believe that many of the images John used already existed in Christian traditions, so it's more likely he drew from Christian sources rather than directly from Muslim ones. It's also possible that both Christian and Islamic mysticism shared common ideas from older philosophical traditions.

See also

In Spanish: Juan de la Cruz para niños

In Spanish: Juan de la Cruz para niños