Fakhr al-Din II facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Fakhr al-Din II

|

|

|---|---|

| فَخْرُ ٱلدِّينِ ٱلثَّانِي | |

Engraving of a portrait of Fakhr al-Din by Giovanni Mariti, 1787

|

|

| Sanjak-bey of Sidon-Beirut | |

| In office December 1592 – 1606 |

|

| Monarch |

|

| Preceded by | Unknown |

| Succeeded by | Ali Ma'n |

| Sanjak-bey of Safed | |

| In office July 1602 – September 1613 |

|

| Monarch |

|

| Preceded by | Unknown |

| Succeeded by | Muhammad Agha |

| Zabit (Nahiya governor) of Baalbek | |

| In office 1625–unknown |

|

| Monarch | Murad IV (r. 1623 – 1640) |

| Preceded by | Yunus al-Harfush |

| Zabit of Tripoli Eyalet nahiyas | |

| In office 1632–1633 |

|

| Monarch | Murad IV |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1572 |

| Died | March or April 1635 (aged c. 63) Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Spouses |

Daughter of Jamal al-Din Arslan

(m. 1590)

Alwa bint Ali Sayfa

(m. 1603)

|

| Relations |

|

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Occupation | Multazim of the following nahiyas:

List

|

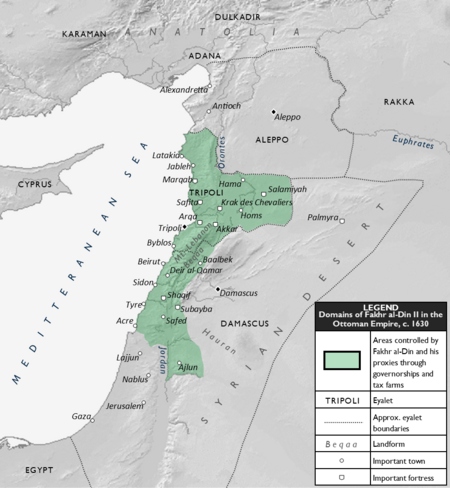

Fakhr al-Din Ma'n (Arabic: فَخْر ٱلدِّين مَعْن, romanized: Fakhr al-Dīn Maʿn; c. 1572 – March or April 1635), also known as Fakhr al-Din II or Fakhreddine II (Arabic: فخر الدين الثاني, romanized: Fakhr al-Dīn al-Thānī), was an important Druze leader in Mount Lebanon. He was a governor for the Ottoman Empire in areas like Sidon-Beirut and Safed. From the 1620s to 1633, he became very powerful across much of the Levant region.

Many people see him as the founder of modern Lebanon. This is because he brought together different parts and communities, especially the Druze and Maronites, under one rule for the first time. Even though he ruled for the Ottomans, he had a lot of independence. He also made strong connections with European countries, which the Ottoman government did not like.

Fakhr al-Din became the leader of the Chouf mountains in 1591, taking over from his father. He was then made governor of Sidon-Beirut in 1593 and Safed in 1602. He joined a rebellion in 1606 but still kept his position. The Ottomans even let him take control of the Keserwan mountains from his rival.

Later, in 1613, the Ottoman Empire sent an army against him. This was because he had allied with Tuscany and had strong forts. He escaped and lived in Tuscany and Sicily for a few years. When he returned in 1618, he quickly regained his old lands. Within three years, he also took over northern Mount Lebanon, which was mostly Maronite.

After a big victory in 1623, he expanded his control to the Beqaa Valley. He also took over forts in central Syria and gained control of Tripoli. He managed to get tax collection rights as far north as Latakia. He often kept the government happy by sending tax money on time and making payments to officials. However, his growing power was seen as a rebellion by the Ottoman government. He surrendered to the Ottomans in 1633 and was executed in Constantinople two years later.

Historian Kamal Salibi said that Fakhr al-Din was a skilled military leader. He also had good business sense and was very observant. While the Ottoman Empire faced economic problems, Fakhr al-Din's lands did very well. Sidon became an important city during his rule. He helped develop farming and started the profitable silk trade in Mount Lebanon.

By opening his port cities to European trade, he brought more European influence to the Levantine coast. Fakhr al-Din became wealthy from collecting taxes and other ways of earning money. He used his wealth to build strong defenses and improve the region's infrastructure. He built palaces in Sidon, Beirut, and his Chouf base, Deir al-Qamar. He also built inns for travelers, bathhouses, mills, and bridges. Some of these buildings are still standing today.

His wealth also paid for his army of professional soldiers. Under his rule, Christians did well and played key roles. His most lasting achievement was creating a strong relationship between the Maronites and Druze. This relationship was very important for the creation of Lebanon.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Fakhr al-Din was born around 1572. He was the oldest of at least two sons of Qurqumaz ibn Yunus. His family, the Ma'n dynasty, were Druze people of Arab origin. They had lived in the Chouf area of southern Mount Lebanon since before the Ottoman Empire took over the Levant in 1516.

The Chouf area was divided into smaller regions called nahiyas. These were part of the Sidon Sanjak, which was a district of Damascus Eyalet. The Chouf and nearby mountain areas were often called "the Druze Mountain." This was because most of the people living there were Druze.

Like his family members before him, Qurqumaz was a local leader called a muqaddam. He also held a tax farm, which meant he collected taxes for the Ottoman government in the Chouf. Local writers called him 'emir', but this was a traditional title, not an official government rank. Fakhr al-Din's mother, Sitt Nasab, came from the Tanukh family, another important Druze family.

The Ottomans considered the Druze to be Muslims for tax purposes. However, they did not always see them as true Muslims. Druze people sometimes had to pretend to be Sunni Muslims to get official jobs. They were also sometimes forced to pay a special tax meant for Christians and Jews. The Ottomans tried to control the Druze and take their weapons. This led to several fights between 1523 and 1585. During a big fight in 1585, Fakhr al-Din's father, Qurqumaz, died while hiding.

The time after Qurqumaz's death and before Fakhr al-Din became known is not very clear. Some historians say that Fakhr al-Din and his brother Yunus were raised by their uncle, Sayf al-Din, for about six years.

Fakhr al-Din's Appearance and Character

Most people who described Fakhr al-Din said he was short. He had olive skin, a reddish face, and bright black eyes. A French consul described him as having a "very majestic air" and a "harmonious voice."

An English traveler named George Sandys said Fakhr al-Din was "great in courage and achievements." He also called him "subtle as a fox." Sandys noted that Fakhr al-Din was "never known to pray, nor ever seen in a mosque." He also said Fakhr al-Din made big decisions only after talking to his mother.

Rise to Power

Becoming Governor of Sidon-Beirut and Safed

Around 1590, Fakhr al-Din took over from his father as the leader of the Chouf. He started collecting taxes for the Ottomans in Sidon and Beirut in 1589. Unlike his family members before him, he worked with the Ottomans. The Ottomans found it hard to control Mount Lebanon without local help.

When a general named Murad Pasha became governor of Damascus, Fakhr al-Din welcomed him with expensive gifts. In December 1593, Murad Pasha made Fakhr al-Din the governor of Sidon-Beirut. This meant Fakhr al-Din gained an official rank as an emir.

The Ottoman Empire was busy with wars against Iran and Austria. This gave Fakhr al-Din a chance to grow his power. Between 1591 and 1594, his tax farms grew to include many areas. These included the Chouf, Matn, Jurd, and parts of the Beqaa Valley. He also gained profits from the ports of Acre, Sidon, and Beirut.

Fakhr al-Din often worked with the Ottomans to get rid of his local rivals. In 1594 or 1595, Murad Pasha ordered Fakhr al-Din to kill a rival leader's son. This helped both Fakhr al-Din and the government.

In 1598, Fakhr al-Din was asked to remove Yusuf Sayfa Pasha, the governor of Tripoli, from Beirut and Keserwan. Fakhr al-Din defeated Yusuf's forces and took control of these areas for a year. This battle started a long rivalry between Fakhr al-Din and the Sayfa family.

In July 1602, Fakhr al-Din became the governor of Safed. He also gained the right to collect taxes in Acre, Tiberias, and Safed. With the Druze of Sidon-Beirut and Safed under his control, he became their main leader. Fakhr al-Din was careful to present himself as a Sunni Muslim to the Ottoman government.

The Janbulad Rebellion and Its Effects

In 1606, Fakhr al-Din joined a Kurdish rebel named Ali Janbulad against Yusuf Sayfa. Fakhr al-Din had ignored government orders to join Yusuf's army. When Janbulad defeated Yusuf, Fakhr al-Din joined forces with the Kurdish rebel.

The rebel allies marched towards Damascus, where Yusuf was. Fakhr al-Din and Janbulad gathered their allies and surrounded Damascus. They defeated Yusuf's troops and looted the city's outskirts. Yusuf escaped, and Fakhr al-Din and Janbulad left after being paid. During this fighting, Fakhr al-Din took over the Keserwan region.

Murad Pasha, who was now a very high-ranking official, moved against Janbulad in 1607. Fakhr al-Din waited to see who would win. When Janbulad was defeated, Fakhr al-Din quickly sent gifts and money to Murad Pasha. This showed how wealthy the Ma'n family was. Murad Pasha decided not to punish Fakhr al-Din.

Fakhr al-Din remained governor of Safed. His son Ali was appointed governor of Sidon-Beirut. Their control of the Keserwan was also officially recognized by the Ottoman government.

First Conflict with the Ottoman Government

Alliance with Tuscany

By the late 1500s, the Medici family, who ruled Tuscany, became more active in the eastern Mediterranean. They wanted to start a new religious war in the Holy Land and supported the Maronite Christians of Mount Lebanon. Fakhr al-Din initially refused to meet with the Tuscans.

After Janbulad's defeat, the Tuscans focused on Fakhr al-Din. They sent him weapons. In 1608, they promised him safety in Tuscany if he supported a future religious war. Fakhr al-Din and Tuscany made a treaty that year. It said Tuscany would give him military help against his rivals. In return, Fakhr al-Din would help Tuscany conquer Jerusalem and Damascus.

Fakhr al-Din became Tuscany's main ally in the region. He gave refuge to the Maronite patriarch in 1609. In 1610, the Pope asked Fakhr al-Din to protect the Maronite community. Fakhr al-Din also reopened the port of Tyre for secret trade with the Tuscans.

Ottoman Expedition of 1613 and Fakhr al-Din's Escape

Fakhr al-Din lost favor with the Ottoman government after a new high-ranking official took power in 1611. The Ottomans were now free from wars and focused on the Levant. They were worried about Fakhr al-Din's growing territory and his alliance with Tuscany. They also disliked that he was strengthening forts and hiring outlawed soldiers.

In 1612, Fakhr al-Din sent money to the new official, but it was not enough. The official demanded that Fakhr al-Din get rid of his soldiers, give up his strong forts, and execute an ally. Fakhr al-Din ignored these orders. He also fought off an attack by the governor of Damascus.

To stop Fakhr al-Din, the Ottomans appointed new governors in nearby areas. Fakhr al-Din tried to avoid direct conflict by sending gifts to the Ottoman authorities. However, he eventually sent his son Ali with 3,000 men to help his allies. Ali defeated the Ottoman forces in May 1613. In response, the Ottomans sent a huge army of 2,000 soldiers and troops from sixty governors against Fakhr al-Din.

Fakhr al-Din put his soldiers in his strong forts, Shaqif Arnun and Subayba. He sent his son Ali to safety in the desert. He also sent a peace offer to Damascus with a large payment, but it was rejected. On September 16, the Ottomans blocked all roads and the port of Sidon to stop Fakhr al-Din from escaping. He bribed an admiral and escaped on a European ship to Tuscany.

During the Ottoman campaign, many of Fakhr al-Din's soldiers and allies left him. This showed how easily alliances could break. The Sayfa family, his rivals, used this chance to get back in favor with the Ottomans. They helped attack Fakhr al-Din's forts and burned his headquarters village, Deir al-Qamar. Fakhr al-Din's brother, Yunus, asked for peace. He sent Fakhr al-Din's mother and other leaders with a large payment to the Ottomans. The Ottomans accepted and stopped the burning of Deir al-Qamar.

Exile in Tuscany and Sicily

Fakhr al-Din arrived in Livorno, Tuscany, on November 3. His arrival surprised the Medici family. The Pope did not want to send military aid to Fakhr al-Din because it might cause a war with the Ottomans. The Medici also wanted to avoid conflict. The Ottomans offered to pardon Fakhr al-Din if he limited trade in Sidon. Negotiations about Fakhr al-Din continued for years.

Fakhr al-Din's own historian did not write much about his time in Tuscany. However, other writings say he lived in Livorno and Florence. He stayed in the apartment of a former Pope in Florence. He asked to stay in Tuscany until it was safe to return home.

Later, Fakhr al-Din moved to Messina in Sicily. The Spanish rulers there probably kept him against his will for two years. They might have used him to threaten the Ottomans. He was allowed to visit Mount Lebanon in 1615 but could not get off the ship. His family and supporters told him that everyone in Chouf was waiting for him.

Fakhr al-Din's Peak of Power

Rebuilding the Ma'nid Lands

In June 1614, the Ottomans changed how Fakhr al-Din's old lands were governed. They created a new province called Sidon to reduce the Ma'n family's power. However, political events in the Ottoman Empire soon helped the Ma'ns. A new official took power, the Sidon province was dissolved, and the governor of Damascus was dismissed. Wars with Iran also started again, drawing Ottoman troops away from the Levant.

The Ottomans reappointed Fakhr al-Din's son Ali as governor of Sidon-Beirut and Safed in December 1615. This was in return for large payments. The Ottomans also destroyed the Ma'nid forts of Shaqif Arnun and Subayba in May 1616.

Despite their official roles, the Ma'ns still faced opposition from their Druze rivals. These rivals were supported by the Sayfa family. The Ma'ns defeated them in several battles. They recaptured Beirut and Keserwan from the Sayfas. Fakhr al-Din's son Ali gave tax collection rights mainly to his uncle Yunus and other allies.

In 1617–1618, there was growing opposition from the Shia Muslims in Safed. They supported efforts to replace Ali as governor. However, Ali was restored to his post in June 1618.

The Ottomans pardoned Fakhr al-Din, and he returned to Mount Lebanon on September 29, 1618. From then on, there was no more active Druze opposition to him. He held a big reception in Acre for leaders from across the Levant. He then moved to collect taxes in the Shia-dominated area of Bilad Bishara. When some Shia families refused to pay, he destroyed their homes. After he captured some Shia refugees, the Shia leaders agreed to accept his rule. Shia soldiers then joined his army in later campaigns.

War with the Sayfas and Control of Maronite Areas

Fakhr al-Din criticized the Sayfa family for their hostility. In 1618 or 1619, he moved against them. He captured their stronghold and besieged Yusuf Sayfa.

During the siege, Fakhr al-Din learned that the Ottoman government had reappointed Yusuf as governor of Tripoli. Fakhr al-Din continued the siege and demanded a large payment from the Sayfas. He also sent soldiers to burn the Sayfas' home village. He gained the loyalty of the Sayfas' men in the forts of Byblos and Smar Jbeil. The governors of Damascus and Aleppo sent troops to help Yusuf. Fakhr al-Din then agreed to accept a payment and lift the siege. Fakhr al-Din's control of the Byblos and Batroun areas was recognized.

In 1621, Fakhr al-Din was ordered to collect unpaid taxes from Yusuf. This gave him a reason to attack the Sayfas again. He captured a fort near Tripoli and besieged the Citadel of Tripoli. Yusuf agreed to sell Fakhr al-Din his properties in exchange for canceling his debts. Fakhr al-Din withdrew from Tripoli in October 1621.

Yusuf was dismissed again in 1622 but refused to give up power. Fakhr al-Din helped the new governor in return for tax collection rights in Tripoli's areas. Yusuf then abandoned Tripoli.

Fakhr al-Din's Maronite ally occupied Maronite-populated Bsharri. This ended the rule of local Maronite leaders. The Maronites of Bsharri likely welcomed this change.

Fakhr al-Din entered Tripoli in March 1623. An imperial order arrived, reappointing Yusuf as governor. Fakhr al-Din insisted that the government's orders be followed. He then escorted the outgoing governor to Beirut. In May or June, Fakhr al-Din supported Yusuf's rebellious nephew. This confirmed the Ma'ns as the practical rulers of Safita.

The Battle of Anjar and Its Aftermath

In 1623, a rival leader stopped the Druze of Chouf from farming their lands. This angered Fakhr al-Din. He placed soldiers in a village and removed the rival family. Meanwhile, the Ottoman authorities had replaced Fakhr al-Din's sons and allies as governors in other areas.

Fakhr al-Din launched a campaign in northern Palestine but was defeated. On his way back, he learned that the Ottoman government had reappointed his sons and allies to their positions. This change was due to a new Sultan and a new high-ranking official who had been paid by Fakhr al-Din's agent. However, the governor of Damascus still launched an attack against the Ma'ns.

Fakhr al-Din arrived in Qabb Ilyas in October. He then raided nearby villages to get back money and supplies lost in the Palestine campaign. The Damascenes, Harfushes, and Sayfas set out from Damascus. Fakhr al-Din gathered his Druze fighters, professional soldiers, and Shia troops.

In early November 1623, Fakhr al-Din defeated the Damascene soldiers at Anjar. He captured the governor of Damascus. Fakhr al-Din made the governor confirm his family's governorships. He also gained control of the southern Beqaa area.

Fakhr al-Din looted Baalbek soon after Anjar. He captured and destroyed its citadel in March. A historian noted that Baalbek was in ruins because of Fakhr al-Din's war. The rival leader of Baalbek was imprisoned and executed in 1625. That same year, Fakhr al-Din became the governor of the Baalbek area.

Taking Over Tripoli and Reaching His Peak

Information about Fakhr al-Din's career after 1624 is limited. Some historians claim that the Sultan recognized him as "ruler of the Land" in 1624, but this is not true.

In 1624, Fakhr al-Din supported a new governor of Tripoli who was denied entry by Yusuf Sayfa. Fakhr al-Din negotiated with Yusuf and gained another four-year tax collection right over Byblos, Batroun, and Bsharri. Yusuf was restored as governor in August, but his control was limited to Tripoli city. Most other areas were held by Fakhr al-Din or his allies.

After Yusuf's death in July 1625, Fakhr al-Din attacked Tripoli. He worked with the new governor against the Sayfas. He forced out an old ally from a fortress and later gained control of other forts from Yusuf's sons. In return, Fakhr al-Din influenced the governor to leave the Sayfas alone. In September 1626, he captured more forts and cities, appointing his own deputies to govern them.

Some sources say Fakhr al-Din was appointed governor of Tripoli in 1627. Ottoman records show that he held tax collection rights for many areas from 1625 to 1630. His tax farms expanded to Jableh and Latakia in 1628–1629. By the early 1630s, it was said that Fakhr al-Din had captured many places around Damascus. He controlled thirty forts and commanded a large army. People said "the only thing left for him to do was to claim the Sultanate."

Fall and Execution

In 1630 or 1631, Fakhr al-Din refused to let Ottoman troops stay in his territory. The Ottoman Sultan, Murad IV, was worried about Fakhr al-Din's growing power. Many complaints about Fakhr al-Din were sent to the Sultan. The Ottomans' victories against their enemies in 1629 likely freed up their forces to deal with Fakhr al-Din.

In 1632, a general named Kuchuk Ahmed Pasha was appointed governor of Damascus. His goal was to defeat Fakhr al-Din. Kuchuk led a large army towards Mount Lebanon. He defeated Fakhr al-Din's forces, and Fakhr al-Din's son Ali was killed. Fakhr al-Din and his men hid in a cave. Kuchuk started fires around the cave to smoke them out. Fakhr al-Din and his men surrendered. His sons Mansur and Husayn had already been captured. His other sons and brother were executed by Kuchuk.

Kuchuk took all of Fakhr al-Din's money and goods. A document from 1634 called Fakhr al-Din "a man well known for having rebelled against the sublime Sultanate." Kuchuk paraded Fakhr al-Din, chained on a horse, through Damascus. Fakhr al-Din was then sent to Constantinople and imprisoned.

In March or April 1635, Fakhr al-Din and his son Mansur were killed on the orders of Sultan Murad IV. Fakhr al-Din's body was displayed in a public square. His wives, who were imprisoned, were also hanged. His relatives were killed by a rival leader. However, his son Husayn, who was still young, was spared. He later became a high-ranking official.

Historians say that Fakhr al-Din's fall was due to more than just military events. His relationship with the Ottoman government was unstable. His victories over local rivals removed any local checks on his power. This eventually led to a strong reaction from the Ottoman Empire. He also relied more on expensive soldiers, which meant he had to collect more money from the people. This risked their support. In 1631, he sold a lot of grain to foreign merchants during a time when food was scarce. This raised food prices and made life harder for people in his lands.

Politics and Economy

Economic Policies

Fakhr al-Din's main goal was to collect enough money to satisfy the Ottoman government. He also wanted to gain favor with the governors of Damascus by making payments. To raise money, he improved farming methods and encouraged trade. An English traveler noted that Fakhr al-Din had gained wealth from locals and foreign merchants. He also rebuilt ruined structures and repopulated abandoned settlements. His main source of income came from the tax farms he controlled. He kept a large part of the tax money because the price he paid the Ottomans remained fixed.

Fakhr al-Din protected farming in his lands. He encouraged growing crops that could be sold for cash, like silk. There was a high demand for silk in Europe. Mount Lebanon became a major silk producer by the mid-1500s. When Fakhr al-Din took control of Tripoli in 1627, he planted thousands of mulberry trees, which are used for silk production. He also sent silk as a gift to Tuscany to encourage trade. Other profitable crops included cotton, grain, olive oil, and wine. In Safed, Fakhr al-Din was praised for "guarding the country" and "promoting agriculture."

After a major naval defeat in 1571, European countries gained more economic influence in the eastern Mediterranean. The Ottoman Empire faced economic problems with high prices and political instability. Fakhr al-Din used these changes to his advantage. He opened the ports of Sidon, Beirut, and Acre to European trade ships. He built inns for merchants and made friends with European powers. Unlike other local leaders who took money from foreign merchants, Fakhr al-Din had good relations with French, English, Dutch, and Tuscan merchants.

Fakhr al-Din used a local merchant to represent him in talks with foreign traders. In 1622, he helped French traders who were captured by pirates. In 1625, many French and Flemish traders moved to Fakhr al-Din's Sidon. Under his rule, Sidon continued to grow. In 1630, the Medici family sent an unofficial consul to Sidon. Historian Salibi noted that Fakhr al-Din's lands attracted European silver.

Fortifications and Troops

Fakhr al-Din used his extra money to build forts and other structures. These helped keep order and stability, which was good for farming and trade. He strengthened forts throughout his career. These included Niha in 1590, and forts in Beirut and Sidon in 1594. After becoming governor of Safed, he gained Shaqif Arnun and Subayba. These forts were well-supplied and guarded. An English traveler noted that Fakhr al-Din's "invincible forts" were ready for a long war. He also built watchtowers to protect his mulberry groves.

Fakhr al-Din kept his army costs low early on. He mainly used local peasant soldiers. These soldiers were always available, even if they were not as skilled as professional ones. European estimates of his forces ranged from 10,000 to 40,000. Peasant soldiers made up most of his army until 1623. However, their main job was farming, which limited how long and how far they could be deployed. As his lands grew, he used fewer peasant armies.

From the 1620s, Fakhr al-Din relied more on professional soldiers. These soldiers were more expensive. He paid for them by taking a larger share of the tax money. These professional soldiers were used for small battles, sieges, patrols, and fighting pirates.

Legacy and Impact

After Fakhr al-Din's fall, the Ottomans tried to undo the unity he created between the Druze and Maronite areas. However, they were not successful. In 1660, the Ottomans reestablished the Sidon province. In 1697, Fakhr al-Din's grandnephew was given the right to collect taxes in the mountain areas. This rule by Fakhr al-Din's family and their relatives, the Shihabs, led to what later became known as the "Lebanese emirate." This system was a step towards the modern Lebanese Republic.

Even though he did not create a Lebanese state, Fakhr al-Din is seen by the Lebanese people as the founder of their modern country. This is because he united the Druze and Maronite areas of Mount Lebanon, the coastal cities, and the Beqaa Valley under one rule for the first time. His most lasting legacy was the strong relationship he started between the Maronites and the Druze. This was very important for Mount Lebanon's history. Since 1920, Lebanese schoolchildren have been taught that Fakhr al-Din was the country's historical founder.

Under Fakhr al-Din's leadership, many Christians moved to the Druze Mountain. The Ottoman campaigns had reduced the number of Druze farmers. Christian migrants helped fill this gap. Druze leaders settled Christians in Druze villages to boost farming, especially silk production. They also gave land to the Maronite Church to encourage Christian settlement. Fakhr al-Din made the first such donation in 1609. While Druze leaders owned much of the land, Christians controlled most other parts of the silk economy.

Fakhr al-Din was known for his religious tolerance. This made Christians living under his rule like him. A historian noted that under Fakhr al-Din, "Christians could raise their heads high." They built churches, rode horses, and carried fancy weapons. Missionaries from Europe also came to Mount Lebanon. This was because his troops and assistants were often Christians.

Building Works

Towards the end of his rule, Fakhr al-Din asked the Medici family for help building modern forts. Tuscan experts, including an architect, arrived in Sidon in 1631. Fakhr al-Din was interested in arts, poetry, and music. However, his main goal for building was practical: to defend his land, help his soldiers move around, and improve life for the people.

Fakhr al-Din's palace in Beirut combined Arabic and Tuscan styles. It had a marble fountain and large gardens. His palace in Deir al-Qamar was built in the Mamluk style. It had little decoration, except for its arched doorway with alternating yellow and white stone. This style is called ablaq.

Experts believe that Fakhr al-Din oversaw the building of water systems and bridges. His building projects in Sidon, Acre, and Deir al-Qamar show the power and wealth he achieved. They also show his role in the revival of the Levantine coast.

Sidon Buildings

Fakhr al-Din built his government house, called a saray, in Sidon as early as 1598. It had a large courtyard, rooms, a fountain, and gardens. It was the tallest building in Sidon. The expansion of trade in Sidon under Fakhr al-Din is also shown by the inns and mosques he built.

Fakhr al-Din is often wrongly credited with building the Khan al-Franj complex. This complex housed the French consul. Fakhr al-Din did build another property, the Dar al-Musilmani, which he may have used as his home. After Fakhr al-Din was captured, his properties in Sidon and other places were taken by the Ottomans. These included dozens of houses, shops, two inns, mills, a soap factory, a coffeehouse, and a bathhouse.

Fakhr al-Din's two inns in Sidon were the Khan al-Ruzz and the Khan al-Qaysariyya. Both were built right on the Mediterranean shore. The Khan al-Ruzz had large storage areas for goods and rooms for visitors. Today, it is in poor condition. The smaller Khan al-Qaysariyya was considered the most beautiful of Sidon's inns. It had a small courtyard and rooms for visitors. Fakhr al-Din also built many shops in the markets around these inns. Some of them are still used today.

Marriages and Children

Fakhr al-Din married at least four women. His first wife was the sister of a leader from the Arslan family. This marriage was arranged around 1590 to ease tensions between different Druze groups. She was known as 'Sultana' and gave birth to his oldest son, Ali. His second marriage was to a woman from his own Druze group, but little else is known about her.

Fakhr al-Din also made peace with the Sayfa family through marriages. In 1613, he married Alwa, the daughter of Yusuf Sayfa's brother. She gave birth to his sons Husayn and Hasan, and a daughter, Sitt al-Nasr. Sitt al-Nasr married Yusuf's son Hasan, and after Hasan died, she married his brother Umar. Another of Fakhr al-Din's daughters married Yusuf's son Beylik. Fakhr al-Din's son Ali also married Yusuf's daughter. In 1617, one of Fakhr al-Din's daughters married Ahmad, a son of Yunus al-Harfush.

Fakhr al-Din's fourth wife was Khasikiyya bint Zafir. She was known for her intelligence and beauty and became his favorite wife. She lived in Sidon, where Fakhr al-Din renovated a palace for her. She was the mother of his sons Haydar and Bulak, and his daughter Fakhira. Khasikiyya went with him during his exile. Fakhr al-Din also had a concubine, who was the mother of his son Mansur.

Family tree

| Genealogical tree of the Ma'n dynasty and their relations with the Tanukh and Shihab dynasties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Paramount Emir of the Druze Dynasties: Ma'n—Outlined in Black; Tanukh—Outlined in Red; Shihab—Outlined in Purple Italic text denotes females Dashed lines denote marriages

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||