Pygmy killer whale facts for kids

The pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata) is a type of oceanic dolphin that lives in the ocean, but it's not seen very often. It is the only species in its group, called Feresa. It's called a "killer whale" because it looks a bit like the bigger orca, also known as the killer whale. Even though it has "whale" in its name, it's actually the smallest animal in the dolphin and whale family to have that word. They can be aggressive when kept in tanks, but they don't act that way in the wild ocean.

The pygmy killer whale was first described by John Edward Gray in 1874. He based his description on two skulls found in 1827 and 1874. The next time one was seen was in 1952. This led to a Japanese scientist, Munesato Yamada, officially naming the species in 1954.

Quick facts for kids Pygmy killer whale |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Pod of pygmy killer whales off of Guam | |

|

|

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Unrecognized taxon (fix): | Feresa |

| Species: |

Template:Taxonomy/FeresaF. attenuata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Template:Taxonomy/FeresaFeresa attenuata (J. E. Gray, 1874)

|

|

|

|

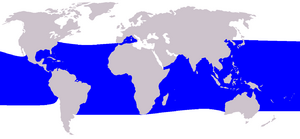

| Range of the pygmy killer whale | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Contents

What Pygmy Killer Whales Look Like

How to Identify Them

Pygmy killer whales are dark gray or black on top. Their sides change sharply to a lighter gray color. The skin around their mouths and on the tip of their noses is white.

They are usually a little over 2 meters (6.5 feet) long. Male pygmy killer whales are considered grown up when they reach 2 meters in length. They have about 48 teeth in total. There are 22 teeth on their top jaw and 26 on their bottom jaw.

These whales usually swim slowly, about 3 kilometers per hour (2 miles per hour). They mostly live in deep ocean waters, from 500 to 2000 meters (1600–6500 feet) deep.

Pygmy killer whales are often confused with melon-headed whales and false killer whales. It can be tricky to tell them apart.

Telling Them Apart

You can tell pygmy killer whales apart from other similar dolphins by a few things:

- Pygmy killer whales have white skin around their mouths that goes back onto their faces.

- Their dorsal fins (the fin on their back) have rounded tips, not pointed ones.

- They have a larger dorsal fin compared to false killer whales.

- The line where their dark top color changes to their lighter side color is very clear.

Their behavior can also help tell them apart. Pygmy killer whales usually move slowly when they are near the surface. False killer whales, however, are much more active. Pygmy killer whales rarely ride the waves made by boats, but false killer whales often do.

It can also be hard to tell them apart if you can't see their head shape clearly. Pygmy killer whales usually don't lift their whole face out of the water when they breathe. This makes it hard to see if they have a rounded "melon" head like some other dolphins.

First Sightings

Before the 1950s, the only proof of pygmy killer whales was from two skulls. One was found in 1827 and another in 1874. In 1952, one was caught in Taiji, Wakayama, Japan. This area is known for its annual dolphin hunts.

Later, in 1958, another one was killed near Senegal. In 1963, 14 pygmy killer whales were caught in Japan and put into tanks. Sadly, all of them died within 22 days. In the same year, one was caught near Hawaii and successfully kept in a tank.

In 1967, a pygmy killer whale near Costa Rica died after getting caught in a fishing net. In 1969, one was killed near St. Vincent, and a group was seen in the Indian Ocean.

What Pygmy Killer Whales Eat

Pygmy killer whales eat many different kinds of food. They have been seen hunting and eating various sea animals. Their diet includes fish, octopus, and squid.

Where Pygmy Killer Whales Live

Pygmy killer whales like to live in warm waters, usually near the equator. They live in the open ocean and are not usually seen in shallow water close to the shore.

You can find pygmy killer whales in warm, tropical, and subtropical waters all over the world. They are often seen near Hawaii and Japan. They are also found in the Indian Ocean near Sri Lanka and the Lesser Antilles. In the Atlantic Ocean, they have been seen as far north as South Carolina and as far east as Senegal.

How They Use Sound

Like other ocean dolphins, pygmy killer whales use echolocation. This means they send out sounds and listen for the echoes to find things. The main sounds they make for echolocation are between 70–85 kilohertz (kHz). This is similar to other dolphins.

When they use echolocation, they make 8 to 20 clicks per second. These clicks are very loud, about 197-223 decibels. The sounds they make are good at traveling in a straight line. This helps them hear things clearly, even with background noise. Scientists believe they make these sounds in a similar way to other dolphins.

Their ears are also built like other dolphins. They have a hollow jawbone and a special fat body that helps them hear. This fat body connects to their inner ear. Hearing tests on pygmy killer whales showed they can hear a similar range of sounds as other dolphins that use echolocation.

How Many Pygmy Killer Whales There Are

Pygmy killer whales have been seen in groups of 4 to 30 or more animals. Scientists have only estimated their population once. They believe there are about 38,900 individuals in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. However, this number could be much higher or much lower.

Protecting Pygmy Killer Whales

Pygmy killer whales sometimes get caught by accident in fishing nets. For example, they make up about 4% of the dolphins caught in large fishing nets used in Sri Lanka.

Like other dolphins and whales, they can have parasitic worms. They can also be attacked by cookie cutter sharks.

Sometimes, groups of pygmy killer whales get stuck on beaches. This is called a mass stranding. Often, one of the whales in the group is sick or hurt. Even if healthy whales are pushed back into the sea, they might come back to the beach. They often stay until the sick whale dies.

The IUCN says that the pygmy killer whale is of "least concern". This means they are not currently in danger of disappearing. They are also protected by several international agreements. These agreements help to conserve small whales and dolphins in different parts of the world.

See also

- List of cetaceans

- Marine biology

In Spanish: Orca pigmea para niños

In Spanish: Orca pigmea para niños