Ford Palace facts for kids

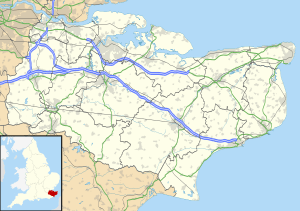

Ford Palace was once a grand home for the Archbishops of Canterbury. It was located in a place called Ford, in Kent, England. This spot is about 11 kilometres (6.6 miles) north-east of Canterbury. It's also about 4.2 kilometres (2.6 miles) south-east of Herne Bay.

The first parts of the palace were built around the year 1300. But people might have used this site for important buildings even earlier. This could have been during the Anglo-Saxon times. It might have been the very first home for the Archbishops outside Canterbury.

Archbishop John Morton (who was Archbishop from 1486 to 1500) rebuilt much of the palace. He added a tall, five-storey brick tower. Later, King Henry VIII visited Archbishop Thomas Cranmer at Ford Palace in 1544. In 1573, Archbishop Matthew Parker thought about tearing it down. But the palace survived for a while longer.

In 1647, during the English Civil War, the English Parliament took over the palace. They found it in good shape. However, most of Ford Palace was pulled down in 1658. Its building materials were sold off. This happened when there was no Archbishop in Canterbury. After the King returned to power in 1660, the land went back to the Church. By 1661, what was left of the palace was so ruined that its chapel was being used as a barn!

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "Ford" is very common in England. It means a shallow place where you can cross a river or stream. At Ford Palace, this name comes from a spot about 146 metres (160 yards) south-west of the palace site. Here, a stream was crossed by an old Roman road. This road connected Canterbury and Reculver.

History of Ford Palace

Early Days

People have lived near Ford for a very long time. Stone tools from the Stone Age have been found nearby. Also, Roman burials and coins have been discovered at the palace site. About 300 metres (330 yards) south of the palace, there might have been a Roman villa. Anglo-Saxon items, like a special glass cup, have also been found.

Some historians in the past thought that King Æthelberht of Kent might have lived at Ford. This was around the year 597. Ford was on the Roman road between Canterbury and Reculver. It was also part of a large estate that was given to the Church in 669. Later, in 949, King Eadred gave this estate to Archbishop Oda of Canterbury.

One historian, Edward Hasted, wrote in 1800 that Ford Palace seemed to be the oldest Archbishop's home after Canterbury. He thought it was built on land given to the Archbishops before the Norman conquest. However, there is no clear proof from old documents or digs that the palace existed during Anglo-Saxon times.

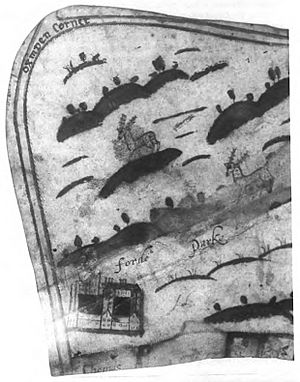

The first real signs of an Archbishop's home at Ford appear in documents from the 1300s and 1400s. Also, part of the main building that stood until 1964 had decorations from around 1300. There might have been an even older site next to the palace, surrounded by a moat.

Archbishop Morton's Work

Archbishop John Morton (1479–1500) did a lot of building work at Ford Palace. He is believed to have "almost rebuilt the whole" palace. He used bricks for his new buildings. Morton was known for building many things during his time as a church leader. He even had a special permission from the King to gather stonemasons and bricklayers for his projects.

Today, parts of Ford Manor farmhouse include brick and stone from the old palace. This includes parts of the palace's gatehouse. A section of the palace's garden wall also remains. Morton is also thought to have built a five-storey brick tower. Nothing of this tower is left above ground. He also built stables. The site of these stables is now a barn, which has parts from the early Tudor period.

Archbishop Cranmer's Time

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1533–1555) really liked Ford Palace. He used it often during the English Reformation. In 1535, he wrote to King Henry VIII from Ford. He wrote about a church leader who disagreed with his ideas against the Pope. In 1536, he wrote from Ford to Thomas Cromwell about family rules.

In 1537, Cranmer left Lambeth Palace for Ford to escape the plague. He had just finished a meeting about a new religious book. In August of that year, he received copies of the Matthew Bible at Ford. He then wrote from there to recommend it to Thomas Cromwell. In 1538, he appointed Nicholas Ridley to a nearby church. Ridley later became a famous martyr with Cranmer.

Cranmer saw Ford Palace as a peaceful place away from London. It was close to Canterbury but not in the busy city. In June 1544, King Henry VIII visited Cranmer at Ford Palace. The King stayed overnight before traveling to Dover. Sadly, during the time when Queen Mary I tried to bring back Catholicism, Cranmer received orders at Ford Palace to appear before the Privy Council. This led to his execution in 1556.

Decline and Demolition

Archbishop Matthew Parker (1559–1575) became Archbishop after Queen Elizabeth I. He did not like Ford Palace. He wanted to tear down parts of it. He wanted to use the materials to improve other homes at Bekesbourne and Canterbury. Parker planned to keep only enough buildings for the park keeper. He wanted to use the manor only for occasional visits.

The estate was rented out as a farm. But Parker wanted Queen Elizabeth I's permission for big changes. In March 1573, he wrote to William Cecil, calling Ford Palace "an old, decayed, wasteful, unwholesome, and desolate house." The decision was not made before Parker died in 1575.

Archbishop George Abbot (1611–1633) was forced to leave his duties in 1627. He temporarily retired to Ford. He spent money on repairs there between 1631 and 1632. But he thought it was a "moorish," or marshy, place.

In 1647, during the English Civil War, Parliament took over Ford Palace. They found it in good condition. But in 1658, Parliament ordered the palace to be mostly torn down. The materials were sold for £840. After the King returned in 1660, the land went back to the Church. A report in 1661 said that "Ford palace is so much ruined... the manor house [is] totally cast down [and] the Chapel made a barn."

In 1667, the old barn and gatehouse were also falling apart. In 1668, it was reported that the person renting the estate had continued tearing down buildings. They had sold "six or seven loads of the best stone." Tiles from Ford were also sold to a nearby church. Even though parts of the palace were used for materials, some parts of the hall and chapel stood until 1964. They were then demolished for a new farm building.

Archaeology and What's Left

Not much archaeological digging has happened at Ford Palace. But some interesting things have been found by chance. These include parts of a Roman inscription and Roman coins. In 2011, some holes were drilled for a building project nearby. They found two strong brick and mortar walls.

Several buildings that were part of the palace still exist today. Parts of Ford Manor farmhouse date back to the 1400s and 1600s. This farmhouse stands where the palace gatehouse once was. A barn north-east of the farmhouse includes much of a Tudor stable block. This stable was originally about 55 metres (182 feet) long. Its roof has special wooden supports called crown posts and tie beams.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |