Frédéric Passy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Frédéric Passy

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Deputy of the 8th arrondissement of Paris | |

| In office 1881–1889 |

|

| Succeeded by | Marius Martin |

| Council member for Seine-et-Oise | |

| In office 1874–1898 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Frédéric Passy

20 May 1822 Paris, France |

| Died | 12 June 1912 (aged 90) Neuilly-sur-Seine, France |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse |

Blanche Sageret

(m. 1847; died 1900) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Profession | Economist |

| Known for | Founding Inter-Parliamentary Union |

| Awards |

|

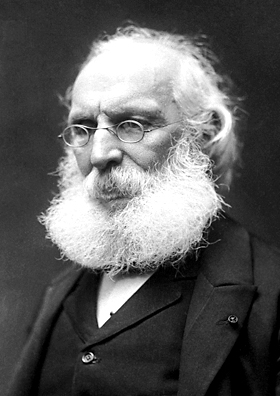

Frédéric Passy (born May 20, 1822 – died June 12, 1912) was a French economist and pacifist. He helped start several important groups that worked for peace, including the Inter-Parliamentary Union. He was also a writer and a politician. He served in the Chamber of Deputies, which is like a parliament, from 1881 to 1889. In 1901, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in the European peace movement. He shared the prize with Henry Dunant, who founded the Red Cross.

Frédéric Passy was born in Paris, France. His family was well-known and had many military and political connections. He studied law and worked as an accountant for a short time. He also served in the National Guard. Soon, he left these jobs to travel around France and give talks about economics. After many years of wars in Europe, Passy joined the peace movement in the 1850s. He worked with other activists and writers to create magazines, articles, and even school lessons about peace.

While he was a member of the Chamber of Deputies, Passy helped create the Inter-parliamentary Conference. This group later became the Inter-Parliamentary Union. He also started several peace societies in France. Passy continued his peace work even when he was older. He died in 1912 after being sick for a long time. Even though his economic ideas didn't become very popular, his work for peace made him known as a leader among European peace activists.

Contents

- Frédéric Passy's Early Life

- The League of Peace

- The Society of Friends of Peace

- Frédéric Passy's Political Career

- Frédéric Passy's Writing Career

- The Nobel Peace Prize

- Frédéric Passy's Final Years

- Illness and Death

- Frédéric Passy's Views

- Frédéric Passy's Family Life

- Legacy

- Selected Works

- Awards and Honours

- See also

Frédéric Passy's Early Life

Frédéric Passy was born in Paris in 1822. His family was from a wealthy background and had strong ties to politics. His father, Justin Félix Passy, was a soldier who fought in the Battle of Waterloo. His grandfather held an important financial position in the old French government. Passy's mother, Marie Louise Pauline Salleron, also came from a well-known Parisian family. Her father ran a successful leather business.

Passy's mother died when he was young, in 1827. His father later remarried.

Starting a Career

From 1846, Passy worked as an accountant for a government council. In 1848, he joined the National Guard. He left his accounting job in 1849 to focus on a career as an economist.

He wanted to teach economics full-time, but he refused to promise loyalty to the French ruler, Napoleon III. Because of this, he couldn't get a permanent teaching job. However, Passy still published many books on economics. Most of these books were based on talks he gave at universities in cities like Pau and Nice.

How His Ideas Developed

Passy studied law, but he became very interested in how societies work and how people should behave. He was inspired by thinkers who believed in economic freedom and reform. He learned from people like Frédéric Bastiat, who thought that military spending and high taxes hurt poor people. Passy built on these ideas, believing that war created problems for everyone, especially the less fortunate.

Even though he grew up in a family of soldiers, Passy said in his autobiography that he could have easily become a supporter of war. But stories about the terrible French conquest of Algeria made him think about how war affects people. Many violent conflicts in Europe in the 1850s led some thinkers to suggest a "United States of Europe." Passy was one of them. In 1859, he said that military action was not the answer to political problems. Instead, he suggested that Europe should have a "permanent congress" to look after everyone's interests and an international police force.

Passy understood how important journalism was for peace. He planned to create a magazine just for "peace messages." This led him to work on The International Mail, a magazine in English and French about the European peace movement.

The League of Peace

Starting the League

In April 1867, a Paris newspaper published letters criticizing France's actions regarding Luxembourg. One of these letters was written by Passy. In his letter, he asked readers to join a "peace league." Many important people supported his idea.

Later that year, the secretary of the Peace Society, Henry Richard, visited Paris. He asked the government to allow an international peace meeting during the 1867 Paris World's Fair. The government said no at first. But they eventually allowed talks about general peace ideas, as long as no questions were asked afterward.

In May 1867, Passy and another economist, Michel Chevalier, got permission to start the International and Permanent League of Peace. In this League, Passy declared "war on war." He believed that if countries had more economic freedom, it would lead to social change and less military spending.

On May 21, Passy gave a speech in Paris about his views on peace. He explained that his ideas came from economic, moral, and philosophical reasons, not religious or political ones. He said that wars fought for defense or independence could be noble. But he strongly condemned wars of conquest because they hurt a country's wealth and moral character.

Another group with a similar name, the League of Peace and Freedom, was started in Geneva that same year. This group was more political and focused on republican ideas. Passy made sure to show that his League was different. He emphasized their "anti-revolutionary aims" and avoided political questions about human rights.

During the Franco-Prussian War

The first major war during the League's existence was the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. After a big battle and the capture of Napoleon III, Passy asked the Prussian king to remember that he had only fought to defend himself, not to attack. He urged the king to stop attacking the French people after their government fell. Passy returned to Paris and tried to get the British and American embassies to help stop the conflict. He even thought about traveling by hot air balloon to see the Prussian king himself. The war deeply saddened Passy, and he was disappointed that the League couldn't stop it.

Who Opposed the League?

Because Passy had clearly separated his group from others, some people opposed his League. One main opponent believed that only quick societal change would bring peace, while Passy's group preferred a slower, legal approach. Some religious groups also protested the League. Efforts to get more Catholic members largely failed.

How the League Was Funded

The League received money from important liberal thinkers, including John Stuart Mill. Its 600 members paid fees, which allowed the League to have a good amount of money in 1868. Founding members paid more, while other members paid a smaller fee.

The Society of Friends of Peace

After the League of Peace ended because of the Franco-Prussian War, peace efforts in Europe got a new boost. This happened after Britain and the United States successfully settled a dispute through arbitration (a way of solving disagreements without fighting).

Passy saw this renewed interest in peace. In 1872, he started working to bring back his League. He explained that society could go down two paths:

- A path of war and revenge, with constant weapons and armies, where young men would spend their lives in military camps.

- A path of peace and law, where arbitration was a key part of European government. This path would use diplomacy to solve problems.

Passy knew that his preferred path of peace wouldn't happen right away. But he began creating a new French peace society to promote arbitration. This group was called the French Society of Friends of Peace.

Other groups also appeared around this time, focusing on arbitration and international law. Passy was involved in some of these groups, which held discussions on how to reduce problems between different communities. He believed these talks were important for building international cooperation.

The 1878 Paris Exhibition

Seeing that the peace movement was growing, members of the Society organized a meeting at the 1878 Paris World's Fair. They told attendees not to bring up "unpleasant" or controversial topics. Delegates from 13 different countries attended, though most were from France. The meeting lasted several days and included many talks:

- A French philosopher named Adolphe Franck opened the meeting. He said that working for peace was good for society. He argued that while war might have helped societies in the past, it was now only a cause of destruction.

- Charles Lemonnier reviewed what previous peace societies had done. He advised against creating a new international organization, saying the movement was still too young. The delegates didn't follow his advice, but he seemed to be right, as it took 13 more years to create such a group.

- As the leader of the Society, Passy disagreed with a statement that said war "makes dictators strong and... makes life worse for the poorest people." He argued that war harms everyone in society, not just the poor. The meeting agreed with Passy's view.

- Several speakers wanted the meeting to create a permanent legal body. They argued that international representatives in a parliament could work together to stop militarists in their countries.

The ten years after the 1878 meeting were slow for the Society. One member noted that meetings often only had Passy and two other people attending.

Joining Forces

In 1889, Passy's Society joined with another group to form the French Society for Arbitration between Nations. This new Society later lost some of its support to other groups, like the Peace Through Law Association, which was started by young Protestants.

Frédéric Passy's Political Career

On April 28, 1873, Passy ran for a seat in the Chamber of Deputies in Marseilles. He ran as an independent candidate but lost the election. However, he was elected to the local council of Seine-et-Oise in 1874 and held that position for 24 years.

In 1881, Passy was elected as a Deputy for Paris. While in the Chamber, Passy continued to promote his ideas about peace. In October 1883, he spoke about the Tonkin campaign, which was a military action by France. He criticized the government's imperialist policy and suggested that the conflict should be settled through arbitration. His ideas were not taken seriously at first. He returned to the issue in December 1885, criticizing France's actions in its colonies. He pointed out that France gave rights to some areas but not to others like Tonkin.

He often spoke against France's taxes on corn and supported free trade. He worked with the Finance Minister to promote these ideas. None of Passy's proposals in the Chamber became law. However, his idea that the government should "take advantage of all good opportunities to talk with other governments to promote arbitration" was supported by 112 members from different political parties.

Passy was re-elected to the Chamber in 1885. He ran again in 1889 but lost the election.

The Inter-parliamentary Conference

In 1887, Passy and a British politician named William Randal Cremer asked their parliaments to support peace agreements between their countries and the United States. Passy gathered 112 signatures from French politicians for this effort. A year later, in November 1888, Cremer led a group of British politicians to meet with French Deputies to discuss working together. This meeting led to the first Inter-parliamentary Conference in 1889. Passy served as its president. This conference later became the Inter-Parliamentary Union, an important international organization.

Frédéric Passy's Writing Career

Passy wrote for several political magazines, including a feminist magazine and a literary-political one. In 1909, he published his autobiography called For Peace: Notes and Documents.

In 1877, Passy became a member of the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences for his work on economics. He was also elected president of the French Association for the Advancement of Sciences in 1881.

Peace Through Education

Passy knew that education was important for achieving peace. He encouraged the creation of a textbook for children aged nine to twelve. His group even offered a prize for an essay for this purpose in 1896. Passy also worked with another activist on a 1906 educational book called Peace and Peace Education. In 1909, they released a whole school program called Pacifist Teaching Course.

The Nobel Peace Prize

As Passy grew older, his health declined. But he was still well-known and respected in the peace movement. Many people thought he would win the first Nobel Peace Prize. The public interest in the prize grew so much that one man even challenged Passy to a duel, saying the prize didn't belong to him!

In December 1901, Passy was awarded half of the first Nobel Peace Prize. He shared it with Henry Dunant, who founded the Red Cross. Each received a large sum of money.

Passy was too old and sick to attend the ceremony in Oslo, Norway. Neither he nor Dunant gave an acceptance speech. Instead, Passy wrote an article to be published after his death. In it, he criticized Alfred Nobel's executors for using his money in ways he didn't intend. He also suggested that the award might weaken the peace movement by attracting people who were only interested in money, not peace. This article was published in a peace magazine in 1926. However, a history professor noted that the prize money was likely used to support Passy's peace work.

Frédéric Passy's Final Years

Passy continued to work for peace in his later years. In 1905, he attended the 14th Universal Peace Congress in Lucerne, Switzerland. This was during a time of rising tensions between France and Germany. He helped calm things down at the meeting by crossing the room and shaking hands with a German pacifist. This was his last public event before he died. A year later, he attended the 15th Universal Peace Congress in Milan, Italy. Delegates from all over Europe and the United States were there. Passy noticed how popular peace activism had become. In 1909, he said that the influence of these international peace meetings was growing each year.

Even with Passy's fame, his economic ideas didn't become very popular in France.

Illness and Death

In May 1912, celebrations were planned for Passy's 90th birthday. But he was too sick to attend. He had planned to give a speech at the celebrations, which was later published.

Passy spent his last months sick in bed. He died in Paris on June 12, 1912. His funeral was simple, without many flowers or grand displays. His friend, a Protestant pastor, led the service.

Frédéric Passy's Views

Religion

Passy was born into a Catholic family and regularly attended church. In the 1850s, he became friends with a priest.

In 1870, the Pope made a declaration that said his word was divine. Passy could not accept this idea of authority. So, his family switched to a more liberal form of Protestantism. Even with his Catholic background, he was supported by people from different religions, like a Protestant pastor and a Jewish Rabbi.

Socialism

While Passy recognized that socialists attended peace meetings, he disagreed with the violence that sometimes came with the labour movement. He thought it hurt efforts to find peace. However, he did agree that socialists had "some points, some very fair hopes, that we would be wrong not to consider."

In 1894, a peace meeting discussed how to involve members of the labour movement more in peace efforts. But Passy argued against this cooperation. He said there was no difference between social classes in a free and democratic society. He suggested that labor movement members should join existing peace societies instead of creating new ones.

Military Service

Even though he served in the National Guard, Passy didn't like the idea of soldiers living in military camps. He believed it led to laziness and gambling. He thought that soldiers should be allowed to develop their "military virtues" within society, not separated from it.

While in the Chamber of Deputies, Passy supported a three-year required military service for all French citizens. But he suggested that those who added to "the intellectual greatness of France" might have a shorter term.

Disarmament

Passy argued that it was impossible to get countries to give up their weapons without first creating groups and systems that promoted international cooperation and arbitration.

Apolitical Views

Like his non-religious views, Passy seemed to be apolitical, meaning he didn't strongly favor one political party. He served as an independent conservative republican. Yet, he often spoke in favor of policies that promoted freedom, like free trade economics.

In August 1898, the Russian Emperor Nicholas II of Russia called for an international meeting to discuss peace. Passy saw this as proof that his neutral and apolitical way of working for peace had succeeded. He believed that leaders would see the negative effects of an "endless arms race" and work together across countries.

Frédéric Passy's Family Life

In 1847, Passy married Marie Blanche Sageret, who came from a wealthy family. Their first son, Paul, was born in 1859. Paul became a famous linguist and founded the International Phonetic Association. Passy's modern ideas about European culture influenced how he raised his children. His son Paul learned four languages as a child but never went to school. Another son, Jean, was born in 1866. He also became a linguist.

Passy and Marie also had a daughter named Marie Louise. Her husband worked for the Chamber of Deputies. In 1912, Marie Louise's 20-year-old daughter died after falling from the Eiffel Tower. She was reportedly upset about her grandfather (Passy) and sister being sick.

Another daughter, Alix, married a man who was an officer in the Legion of Honour.

|

Legacy

Passy's approach to peace, which focused on solving problems through arbitration and international cooperation, continued long after his death. Peace activists kept working for formal agreements on issues like the rights of foreign visitors and settling land disputes.

In 1927, his son Paul published a book about his father's life called An Apostle of Peace: The Life of Frédéric Passy.

Several roads have been named after Passy in cities like Nice and Neuilly-sur-Seine. In March 2004, the Inter-Parliamentary Union recognized Passy's efforts in creating the organization. They opened the Frédéric Passy Archive Centre in Paris in his honor.

Selected Works

Books

| Title | English translation | Time of first publication | First edition publisher/publication | Unique identifier | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mélanges économiques | Economic Mixtures | 1857 | Paris, Guillaumin | ||

| Leçons d'économie politique faites à Montpellier | Political Economy Lessons Made in Montpelier | 1862 | Paris, Guillaumin | ||

| La démocratie et l'instruction: discours d'ouverture des cours publics de Nice, 1863-1864 | Democracy and Education: Opening Speech of Public Courses in Nice, 1863-1864 | 1864 | Paris, Guillaumin | ||

| Pour la paix; notes et documents | For Peace: Notes and Documents | 1909 | Paris, Fasquelle |

Articles

| Title | English translation | Time of publication | Journal | Volume (Issue) | Page range | Unique identifier | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "The Armaments of the Future - where will they stop?" | 1895 | The Advocate of Peace | 57 (5) | 101–103 | JSTOR 20665295 | ||

| "Peace Movement in Europe" | Jul 1896 | American Journal of Sociology | 2 (1) | 1–12 |

Awards and Honours

- Legion of Honour (1895)

- Nobel Peace Prize (1901)

- Legion of Honour – Commander (1903)

See also

In Spanish: Frédéric Passy para niños

In Spanish: Frédéric Passy para niños

- List of peace activists

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |