Francesco Bianchini facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

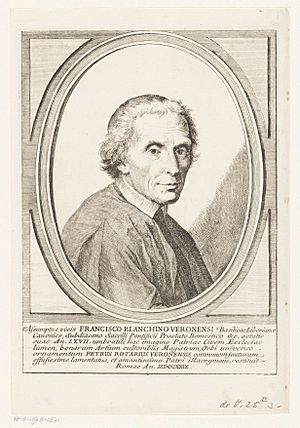

Francesco Bianchini

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 13 December 1662 Verona, Republic of Venice |

| Died | 2 March 1729 Rome, Papal States |

| Burial place | Verona Cathedral |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Alma mater | University of Padua |

| Occupation | Astronomer, historian, art historian |

| Movement | Scientific Revolution |

Francesco Bianchini (born December 13, 1662 – died March 2, 1729) was a brilliant Italian thinker and scientist. He worked for important religious leaders, including Pope Clement XI. He even helped figure out the best way to calculate the correct date for Easter each year.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Francesco Bianchini was born into a noble family in Verona, Italy. His parents were Giuseppe Bianchini and Cornelia Vailetti. He received his education from the Jesuits in Bologna. He also studied with Geminiano Montanari, a famous astronomer from Padua.

Bianchini spent most of his university years at the University of Padua. While studying theology, he also focused on astronomy, especially comets. This early interest in space and science shaped his future work. In 1684, he moved to Rome. There, he became a librarian for Cardinal Ottoboni. When Ottoboni became Pope Alexander VIII in 1689, he gave Bianchini important roles. These included being a papal chamberlain and a canon of Santa Maria Maggiore.

Contributions to Science

Bianchini was a well-respected scientist in his time. In 1713, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society in London. This was a very important scientific group. Sir Isaac Newton himself suggested Bianchini for this honor. A few years earlier, in 1706, Bianchini also became a member of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris.

Studying Venus and Earth

Bianchini was very interested in the planet Venus. He tried to figure out how fast Venus spins. He used a special telescope that was 100 feet long! Today, we know this is impossible to do from Earth. Venus is covered in thick clouds, so we cannot see its surface.

He also studied the distance to Venus. Bianchini measured how the Earth's spin axis slowly wobbles. This wobble is called precession.

Improving the Calendar

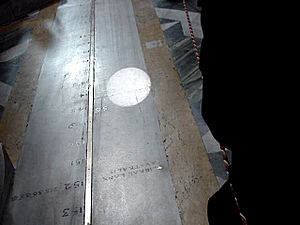

Pope Clement XI asked Bianchini to help improve the calendar. Bianchini built a special device called a gnomon in a church in Rome. This church is called the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri. This device helped to accurately track the sun's position. It also helped to calculate the correct dates for religious holidays like Easter.

Pope Benedict XVI later explained why astronomy was so important back then. Before accurate clocks, knowing the sun's position helped people tell time. It also helped them know when to say daily prayers.

Bianchini's ideas about the Copernican system are not fully clear. This system says that the Earth and planets orbit the Sun. In his book about Venus, the picture of the solar system had an empty center. This might suggest he was careful about fully supporting the idea.

Honors and Legacy

Bianchini's work was so important that several things are named after him:

Archaeology and Later Life

Besides science, Bianchini was also an expert in ancient Rome. He worked as a topographer (someone who maps land features) and an archaeologist. He also collected ancient artifacts.

In 1726, a special burial place was found near the Appian Way. It was called the columbarium of Livia. This structure had three rooms for the servants of Augustus and his wife Livia. Bianchini explored these rooms and wrote about them.

In 1727, he had a serious accident. He was exploring the ruins of the palace of the Caesars on the Palatine Hill. He fell through the ceiling of a vault and was badly hurt.

Francesco Bianchini died in Rome on March 2, 1729, at the age of 66. He was buried in Santa Maria Maggiore. A monument was built in his memory in the Verona Cathedral.

Key Books and Writings

Bianchini wrote many important books during his lifetime. Some of his most famous works include:

- Storia universale, provata co' monumenti, e figurata co' simboli degli antichi (1697): A universal history.

- De Calendario et Cyclo Caesaris (1703): About the calendar.

- Camera Ed Inscrizioni Sepulcrali De' Liberti, Servi, ed Ufficiali della Casa di Augusto Scoperte nella Via Appia, ed illustrate Con le Annotazioni (1727): About the burial chambers he explored.

- Hesperi et Phosphori nova phaenomena sive observationes circa planetam Veneris (1728): This book was about his observations of Venus. In it, he suggested Venus spins in 24 days and 8 hours.

See also

- List of largest optical telescopes in the 18th century