Francis Atterbury facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Right Reverend Francis Atterbury |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rochester | |

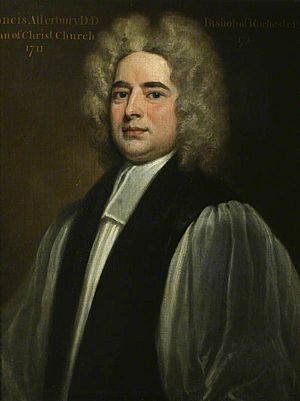

Francis Atterbury by Godfrey Kneller

|

|

| Diocese | Diocese of Rochester |

| In Office | 1713–1723 |

| Predecessor | Thomas Sprat |

| Successor | Samuel Bradford |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1687 |

| Consecration | 1713 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 March 1663 Middleton, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Died | 22 February 1732 (aged 68) Paris, France |

| Buried | Westminster Abbey |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Education | Westminster School |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

Francis Atterbury (born March 6, 1663 – died February 22, 1732) was an important English writer, politician, and church leader. He was a bishop in the Church of England. Atterbury was a strong supporter of the High Church Tories. This group believed in the importance of the Church and the King. He also supported the Jacobites, who wanted to bring back the old royal family.

Queen Anne liked Atterbury and gave him important jobs. But later, new leaders from the Hanoverian Whig party did not trust him. These Whigs were rivals of the Tories. Atterbury was eventually sent away from England. This happened because he was caught talking with the "Old Pretender." The Pretender was a person who claimed to be the rightful king. This event was known as the Atterbury Plot. Atterbury was also known for being very clever and a great speaker.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Francis Atterbury was born in Middleton, Buckinghamshire, England. His father was a rector, which is a type of church leader. Francis went to Westminster School and then Christ Church, Oxford. At Oxford, he became a tutor, helping other students learn.

In 1687, he wrote a book called An Answer to some Considerations. This book was a reply to someone who had attacked the Protestant Reformation. Atterbury's writing was very strong and powerful. Some people even accused him of treason because of his words.

Becoming a Church Leader

After a big change in government called the "Glorious Revolution," Atterbury supported the new rulers. He became a priest in 1687. He was known for his great speeches in London. Soon, he was chosen as one of the royal chaplains, serving the King or Queen.

He spent most of his time at Oxford. There, he helped Henry Aldrich, who led Christ Church. This college was a strong center for the Tory party. Atterbury also helped a student, Charles Boyle, write a book. This book attacked a famous scholar named Richard Bentley. Bentley later proved that Atterbury's arguments were not based on good facts.

Leading the High Church Party

In the early 1700s, there was a big split in the Church. Some people were "High Church" and others were "Low Church." Most church leaders were High Church. Atterbury strongly supported the High Church side. He wrote many books and articles. Many people saw him as a brave defender of the clergy's rights.

In 1701, he became an Archdeacon and got a special position at Exeter Cathedral. The University of Oxford gave him a Doctor of Divinity degree. In 1704, Queen Anne made him the Dean of Carlisle Cathedral.

In 1710, a church leader named Henry Sacheverell was put on trial. This caused a huge wave of support for the High Church. Atterbury was very important during this time. He helped write Sacheverell's speech for the trial. He also wrote many pamphlets, which are small books, to turn people against the Whig government.

When the government changed, Atterbury received many rewards. He became the leader of the lower house of the Convocation, which is like a church parliament. In 1711, Queen Anne made him the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford.

However, Atterbury was not a good dean at Christ Church. Some people said he was made a bishop because he was so bad at being a dean! In 1713, he became the Bishop of Rochester. This job also included being the Dean of Westminster Abbey. Many thought he would become the Archbishop of Canterbury, the highest church leader in England.

Supporting the Jacobites

Atterbury was worried about the new royal family, the House of Hanover. They favored the Whigs, not the Tories. He likely hoped to help put James Francis Edward Stuart, the "Old Pretender," on the throne after Queen Anne died.

But Queen Anne died suddenly. Atterbury had to accept the new king. He tried to get along with the new royal family. However, they did not trust him. He became a strong opponent of the government. In the House of Lords, his speeches were clear and lively. He wrote many of the protests found in the records of the Lords. He also wrote pamphlets that criticized the new rulers.

When the rebellion of 1715 started, Atterbury refused to sign a paper supporting the new Protestant king. In 1717, he began to talk directly with James Francis Edward Stuart, the Pretender. Records show that Atterbury was a secret leader in a Jacobite group called the Order of Toboso.

Arrest and Exile

| Attainder of Bishop of Rochester Act 1722 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to inflict Pains and Penalties on Francis, Lord Bishop of Rochester. |

| Citation | 9 Geo. 1. c. 17 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 27 May 1723 |

In 1721, a plot was discovered to capture the royal family and make "King James III" the ruler. Atterbury was arrested with others involved in this Atterbury Plot. He was held in the Tower of London for several months. He had been very careful in his letters with the exiled royal family. There was enough proof to be sure he was guilty, but not enough for a normal court trial.

So, in 1723, a special law was passed against him. This law took away his church titles. It also banished him from England for life. No British person was allowed to talk to him without the king's permission. The law passed in the House of Lords by a vote of 83 to 43.

Atterbury said goodbye to his loved ones with dignity. He continued to say he was innocent, even though it wasn't true. He went to Paris, France, and became a leader among the Jacobite refugees there. The Pretender invited him to Rome, but Atterbury felt a Church of England bishop shouldn't be in Rome.

For a while, he was very close to James, the Pretender. They wrote to each other often. Atterbury was like a prime minister to a king without a kingdom. But soon, he felt his advice was not being listened to. In 1728, he left Paris and moved to Montpellier. He stopped being involved in politics and focused on writing.

Later Life and Death

Six years after being exiled, Atterbury became very ill. His daughter, Mrs. Morice, who was also very ill, traveled to see him one last time. He met her in Toulouse, and she died that night after he gave her the last rites.

Atterbury recovered from the shock of his daughter's death. He returned to Paris and continued to serve the Pretender. In his ninth year of exile, he wrote a book defending himself against someone who said he had changed a famous history book. Atterbury said he was not involved in editing that book.

Francis Atterbury died on February 22, 1732, at the age of 68. His body was brought back to England. He was buried in Westminster Abbey. In his papers, he had asked to be buried "as far from kings and politicians as may be." He is buried near a tourist information booth. His simple black grave slab shows his name and dates.

Atterbury was close friends with many famous writers of his time. These included Joseph Addison, Jonathan Swift, John Arbuthnot, John Gay, Matthew Prior, and Alexander Pope. Pope even asked Atterbury for advice on his writing.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |