Richard Bentley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Bentley

DD, FRS

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 27 January 1662 Oulton, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England

|

| Died | 14 July 1742 (aged 80) Cambridge, England

|

| Alma mater | St John's College, Cambridge |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Dissertation on the Letters of Phalaris (1699) |

| Title | Regius Professor of Divinity |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Notable students | |

| Influenced | Richard Porson, A. E. Housman |

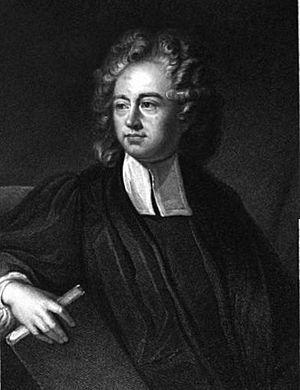

Richard Bentley was a very smart English scholar, critic, and religious thinker. He lived from 1662 to 1742. Many people think he was the "founder of historical philology", which means he was a pioneer in studying languages and texts from the past in a scientific way. He's also known for starting the English way of studying ancient Greek culture. A famous scholar named A. E. Housman even called him "the greatest scholar that England or perhaps that Europe ever bred".

One of Bentley's most famous works was his Dissertation upon the Epistles of Phalaris, published in 1699. In this book, he proved that a collection of letters, supposedly written by a Sicilian ruler named Phalaris in the 6th century BCE, were actually fake. They were written much later by a Greek writer in the 2nd century CE. Bentley's careful investigation of these letters is still seen as a major achievement in checking old texts for accuracy. He also discovered that a certain sound, represented by the letter digamma in some old Greek writings, was also present in the poems of Homer, even though it wasn't written down.

In 1700, Bentley became the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. He was a strong leader, and sometimes his strict ways caused arguments with other college members. But he stayed in that important job for over forty years until he died. In 1717, he was also made the Regius Professor of Divinity at the University of Cambridge. While at Cambridge, Bentley started the first competitive written exams in a Western university.

Bentley was also a member of the Royal Society, a group for important scientists. He was interested in how science could explain the world and believed it showed a Creator. He even talked about these ideas with the famous scientist Isaac Newton. Bentley was in charge of the second edition of Newton's famous book, Principia Mathematica. However, he let his student Roger Cotes do most of the scientific work.

Contents

Early Life and School

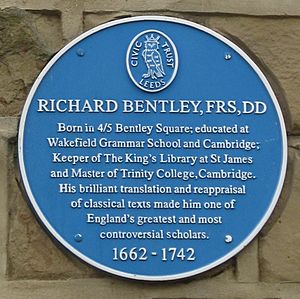

Richard Bentley was born on January 27, 1662. He was born at his grandparents' home in Oulton, near Leeds, England. There's a blue plaque there today to remember him. His father, Thomas Bentley, was a farmer. His grandfather, Captain James Bentley, faced difficulties after the English Civil War, which left the family with less money. Richard's mother, who had some education, taught him his first lessons in Latin.

After going to a grammar school in Wakefield, Bentley started at St John's College, Cambridge in 1676. He later earned a scholarship and received his first university degrees in 1680 and 1683.

Academic Career

Bentley didn't become a college professor right away. Instead, he became the headmaster of Spalding Grammar School before he was 21. Later, Edward Stillingfleet, a church leader in London, hired Bentley to teach his son. This job helped Bentley meet important scholars and use one of the best private libraries in England. During his six years as a tutor, Bentley studied ancient Greek and Latin writers very deeply. This knowledge helped him a lot in his later work.

In 1689, Stillingfleet became a bishop, and Bentley's student went to Wadham College, Oxford. Bentley went with him. At Oxford, Bentley met other scholars and studied old handwritten books in famous libraries like the Bodleian Library. He collected information for his studies, including notes on Greek poets and dictionaries.

The Oxford University Press was preparing to publish an old Greek history book called Chronographia by John Malalas. The editor, John Mill, asked Bentley to review it. Bentley wrote a long paper called Epistola ad Johannem Millium, which was added to the end of the Oxford Malalas in 1691. This paper showed how brilliant Bentley was. He could easily fix mistakes in old texts and understood the material very well. Other scholars quickly saw that he was an amazing expert.

In 1690, Bentley became a deacon in the church. In 1692, he was chosen to give the first Boyle Lectures, which were talks about science and religion. He gave these lectures again in 1694. In his first series of lectures, he explained Newtonian physics in a simple way. He used these scientific ideas to argue that an intelligent Creator must exist. He even exchanged letters with Newton about it.

After becoming a priest, Bentley received a special church position at Worcester Cathedral. In 1695, he became a royal Chaplain. That same year, he was elected a member of the Royal Society, and in 1696, he earned his Doctor of Divinity degree.

His Famous Book on Phalaris

Bentley had official rooms in St James's Palace and was in charge of the royal library. He worked hard to fix up the collection, which was in bad shape. He also made sure that publishers sent nearly a thousand books that had been bought but not delivered.

The University of Cambridge asked Bentley to get special Greek and Latin fonts for their classical books, which he had made in Holland. He also helped John Evelyn with his book on ancient coins. Bentley didn't always finish the big projects he started. For example, he planned an edition of Philostratus but gave up on it.

His most important academic work, the Dissertation on the Epistles of Phalaris (1699), came about almost by chance. In 1697, another scholar named William Wotton asked Bentley to write a paper proving that the Epistles of Phalaris were fake. This had been a debated topic for a long time. The editor of Phalaris, Charles Boyle, was upset by Bentley's paper. Boyle wrote a response that many people liked, even though it wasn't very deep. When Bentley replied, he wrote his famous dissertation. At first, not everyone accepted his findings, but today it's seen as a brilliant piece of work.

Master of Trinity College

In 1700, Bentley was chosen to be the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. He was an outsider, but he quickly started to improve how the college was run. He began a project to renovate the buildings and used his position to encourage learning. He is also known for starting the first written exams in the Western world in 1702. Before this, all exams were spoken. However, his changes and the cost of renovations made the other college members angry because it reduced their income.

After ten years of arguments, the college members complained to the Bishop of Ely, who was the college's official visitor. They listed many complaints about Bentley. Bentley wrote a strong reply defending himself. The college members then added more specific charges against him. Bentley appealed directly to the King.

The lawyers decided against Bentley, and a decision was made to remove him from his position. But before this could happen, the Bishop of Ely died, and the process stopped. The arguments continued in different ways. In 1718, Cambridge University even took away Bentley's degrees as punishment for not appearing in court. It wasn't until 1724 that he got them back.

In 1733, the college members tried again to remove Bentley. He was sentenced to be removed, but the person who was supposed to carry out the sentence, Richard Walker, was Bentley's friend and refused to do it. Even though the arguments went on for about 30 years, Bentley remained in his job until his death.

Later Studies

Even with all the arguments, Bentley continued his studies, though he didn't publish as much. In 1709, he added an important section to John Davies's edition of Cicero's Tusculan Disputations. The next year, he published corrections to plays by Aristophanes and fragments of other Greek writers. He published this work using the pen name "Phileleutherus Lipsiensis." He used this name again two years later in his Remarks on a late Discourse of Freethinking, which was a reply to a philosopher named Anthony Collins. The university thanked him for this work, as it supported the Church of England.

Bentley had studied the Roman poet Horace for a long time. He quickly wrote his edition of Horace and published it in 1711. He did this to gain public support during a difficult time in his arguments at Trinity College. He focused on correcting the text. Some of his hundreds of corrections have been accepted, but many were later seen as unnecessary, even though they showed his vast knowledge.

In 1716, Bentley announced his plan to create a corrected edition of the New Testament. For the next four years, he collected materials for this huge project. In 1720, he published his plans, showing how he would compare the Latin Bible (the Vulgate) with the oldest Greek manuscripts. He wanted to restore the Greek text to how it was when the early church leaders met at the First Council of Nicaea. He used important manuscripts like Codex Alexandrinus, which he called "the oldest and best in the world." Many people offered money to support the publication, but he never finished the work.

His edition of the Roman playwright Terence (1726) is considered more important than his Horace. Along with his Phalaris work, it greatly shaped his reputation. In 1726, he also published the Fables of Phaedrus.

His work on John Milton's Paradise Lost (1732), suggested by Queen Caroline, is often seen as his weakest. He suggested that Milton, who was blind, had used a helper to write and that an editor had added mistakes. It's not clear if Bentley truly believed his own ideas on this. Even A. E. Housman, who called him the greatest scholar, criticized his understanding of poetry.

Bentley never published his planned edition of Homer, but some of his notes are kept at Trinity College. These notes are important because he tried to fix the poem's rhythm by adding the lost digamma sound.

Family Life

In 1701, Bentley married Joanna, the daughter of Sir John Bernard, 2nd Baronet. They had three children: a son named Richard (1708–1782), who became a writer and artist, and two daughters. One daughter, Johanna, married Denison Cumberland in 1728. Their son, Richard Cumberland, became a well-known playwright.

Later Years

In his old age, Bentley continued to read and enjoyed spending time with friends and younger scholars. He died from a lung illness called pleurisy on July 14, 1742, at the age of 80.

Legacy

Bentley left about £5,000 when he died, which would be worth a lot more today. He gave some old Greek manuscripts to the Trinity College library. His other books and papers went to his nephew, also named Richard Bentley. When his nephew died, those papers also went to the Trinity College library. The British Museum later bought many of his books, which had valuable notes written in them.

Bentley is still honored today at Spalding Grammar School, where he was once a headmaster. One of the school's houses is named Bentley, and the students in that house wear blue. The school also publishes an annual magazine called the Bentlian, named after him.

Many experts believe Bentley was the first Englishman to be considered among the greatest classical scholars. The modern German way of studying languages and texts recognized his genius. One scholar, Bunsen, said Bentley "was the founder of historical philology."

Bentley inspired a whole generation of scholars in England who studied ancient Greek. He taught himself and created his own way of studying. He won his academic arguments, like the one about the Phalaris letters. Some writers, like Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift, criticized him, showing they didn't always understand how important his work was.

Bentley was unique at a university where most people focused on teaching or religious debates. He developed his deep knowledge and original ideas before 1700. After that, he didn't learn much new and only published occasionally. However, A. E. Housman believed that Bentley's edition of Manilius (1739) was his greatest work.

Images for kids

Works

Major Works

- Works of Richard Bentley, collected by Alexander Dyce, 1836. This collection includes his famous Dissertations upon the Epistles of Phalaris.

- Epistola ad Joannem Millium (Letter to John Mill).

Other Works

- Astronomica of Manilius (1739)

- Notes on the Theriaca of Nicander and on Lucan, published after his death.

- Corrections to plays by Plautus.

- Bentleii Critica Sacra (1862), which includes his work on the epistle to the Galatians.

- A Confutation of Atheism from the Origin and Frame of the World (1692), a sermon.

- Remarks upon a late Discourse of free-thinking (1725).

Letters

- Bentlei et doctorum-virorum ad eum Epistolae (1807)

- The Correspondence of Richard Bentley, edited by C. Wordsworth (1842)

See also

In Spanish: Richard Bentley para niños

In Spanish: Richard Bentley para niños

- Bentley's paradox

- Trinity College Clock

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |