Gay Head Light facts for kids

Quick facts for kids  |

|

| Gay Head Light | |

|

|

|

| Location | Aquinnah, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°20′54.4″N 70°50′5.8″W / 41.348444°N 70.834944°W |

| Year first constructed | 1799 |

| Year first lit | 1856 (current structure) |

| Automated | 1960 |

| Foundation | Granite stone on cement |

| Construction | Brick and sandstone |

| Tower shape | Conical |

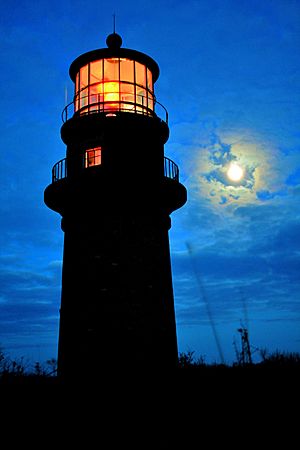

| Markings / pattern | Red brick with black lantern |

| Focal height | 170 feet (52 m) |

| Original lens | First order Fresnel lens |

| Current lens | DCB-224 |

| Range | White 24 nautical miles (44 km; 28 mi) Red 20 nautical miles (37 km; 23 mi) |

| Characteristic | |

| Fog signal | none |

| Admiralty number | J0476 |

| USCG number | 1-620 |

The Gay Head Light is a famous historic lighthouse located on the westernmost tip of Martha's Vineyard in Aquinnah, Massachusetts. It stands proudly on the cliffs, guiding ships safely past dangerous underwater rocks known as "Devil's Bridge." This lighthouse has been a vital aid to navigation for over 200 years, helping countless vessels travel through the busy waters of Vineyard Sound.

Contents

History of Gay Head Light

Building the First Lighthouse (1799)

After the United States became a country, one of the first things its government did was take charge of lighthouses. These lights were super important for guiding ships. In 1796, a senator from Massachusetts, Peleg Coffin, asked for a lighthouse to be built on Martha's Vineyard. He knew the waters near the Gay Head cliffs were very dangerous.

President John Adams approved the lighthouse in 1798. The goal was to make it safer for ships passing through the busy Vineyard Sound. In 1799, Massachusetts gave the land to the U.S. government. A builder named Martin Lincoln constructed the first lighthouse. It was a 47-foot tall wooden tower with eight sides, sitting on a stone base. There was also a house for the lighthouse keeper and a place to store whale oil.

The first white person to live in Gay Head was Ebenezer Skiff, who became the lighthouse keeper in 1799. He lit the lamp for the first time on November 18, 1799. The light came from "spider lamps" that burned sperm whale oil. These lamps produced a lot of smoke, which made the keeper's eyes burn and smudged the glass. Keepers often had to wear a veil! The light flashed white, thanks to a rotating system powered by a wooden clockwork. Sometimes, when it was cold, the wood would swell, and Keeper Skiff had to turn the light by hand. He even hired local Wampanoag people to help him.

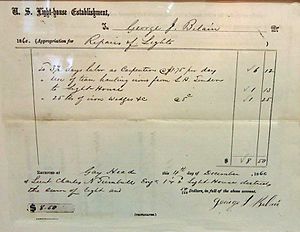

Keeper Skiff's job was tough. The nearby clay cliffs would send clay dust onto the glass, making it even harder to keep clean. He also had to carry water from far away because the local spring wasn't enough. In 1805, he wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, asking for a raise. President Thomas Jefferson approved a $50 raise, bringing his salary to $250 a year. Skiff served as keeper for 29 years!

Changes and Upgrades (1838-1854)

Around 1838, the lighthouse got a new lens system with 10 parabolic reflectors. The lantern was also lowered to help the light cut through fog. An inspection in 1838 noted that the light rotated every four minutes and could be seen for over 20 miles. A Benjamin Franklin lightning rod was also added to the top of the lighthouse. This was important because tall lighthouses often got hit by lightning. You can still see a cracked lightning rod ball from the Gay Head Light at the Martha's Vineyard Museum!

By 1842, the original wooden lighthouse was falling apart. A civil engineer named I.W.P. Lewis reported that it was "decayed in several places" and needed to be replaced. Even the keeper's house was "shaken like a reed" during storms. Despite these warnings, the lighthouse wasn't replaced right away. In 1844, the wooden tower was simply moved back 75 feet from the eroding cliffs.

In the early 1850s, a new group called the Light House Board took over managing lighthouses. They decided to replace the old wooden tower with a strong brick one.

The New Brick Lighthouse (1854-1874)

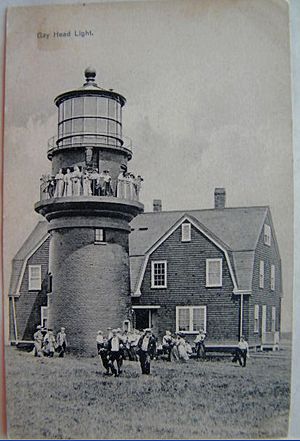

In 1854, Congress approved $30,000 to build a new brick tower and keeper's house. The new lighthouse, which is the one you see today, was started in 1854 and first lit in 1856. It was built with red bricks made nearby.

The most exciting part was the new lens: a first-order Fresnel lens. This amazing lens was about 12 feet tall and weighed several tons. It had 1,008 handmade crystal prisms! The U.S. Lighthouse Board ordered this special lens from Lepaute Manufacturing in France. It was so impressive that it won a gold medal at the World's Fair in Paris in 1855 before being shipped to America.

Moving the huge Fresnel lens from the docks in Edgartown to the Gay Head cliffs was a massive task. It took 40 pairs of oxen to pull the heavy lens and its machinery over 20 miles of dirt and sandy roads! The new Gay Head Lighthouse was activated on December 1, 1856. It became very popular, and many tourists visited by steamship to see its powerful new light.

In 1874, the light's signal was changed from just flashing white to "three whites and one red." This helped sailors tell it apart from other lighthouses nearby. To do this, red screens were added to every fourth row of prisms on the rotating Fresnel lens. The lamp inside used five wicks and burned about two quarts of oil an hour. Over the years, the lighthouse changed fuels from sperm whale oil to lard oil (in 1867) and then to kerosene (in 1885).

Keepers and Automation (1874-1988)

Lighthouse keepers and their families lived at the Gay Head Light for many years. One keeper, Crosby L. Crocker, served from 1892 to 1920. Sadly, several of his children died mysteriously while living in the brick keeper's house. It was later believed that toxic mold and mildew on the damp brick walls caused their illnesses. Because of this, a new, larger wooden keeper's house was built in 1902.

In 1920, Charles W. Vanderhoop, Sr., became the tenth Principal Lighthouse Keeper. He was special because he was the only Wampanoag person to officially be a keeper of the light. He was known for his great storytelling. He even gave a tour to former President Calvin Coolidge, who famously said the view was "Beautiful."

In 1954, the Gay Head Light got electricity! The old Fresnel lens was replaced by a powerful electric beacon called a Carlisle & Finch DCB-224 aero beacon. This beacon was designed to keep the "three whites and one red" signal. By 1956, the lighthouse was fully automated, meaning a keeper no longer needed to live there. The wooden keeper's house was torn down around 1960.

The original Fresnel lens was moved to the Martha's Vineyard Museum in Edgartown, Massachusetts, where you can still see it today. In 1988, the light's signal was changed again, to "one white and one red."

Saving the Gay Head Light

After 1956, the U.S. Coast Guard maintained the automated Gay Head Light. However, in the 1970s and 1980s, due to money shortages, many lighthouses were set to be destroyed. This was because new technologies like GPS made them less vital for navigation. The Gay Head Light, along with two other Martha's Vineyard lighthouses, was on this "Doomsday List."

Luckily, a nonprofit group called Vineyard Environmental Research Institute (VERI) stepped in. They worked with Senator Edward Kennedy and Congressman Gerry Studds to save the lighthouses. In 1985, the Coast Guard gave VERI a 35-year license to manage and maintain the Gay Head Light. This was the first time active lighthouses in the U.S. were given to a civilian organization!

VERI raised money through events with local supporters and celebrities like historian David McCullough and singer Carly Simon. The money helped restore the lighthouse, fixing brick walls, removing mold, replacing windows, and cleaning the spiral staircase.

In 1987, the Gay Head Light was added to the National Register of Historic Places, recognizing its importance.

Visiting the Lighthouse

The Gay Head Light has always welcomed visitors. Old photos show people on the lighthouse balcony and around the grounds. After the famous Fresnel lens was installed in 1856, even more tourists came. Special steamship trips brought people to the cliffs, where oxcarts waited to take them to the lighthouse.

A writer in 1857 described the amazing view from the lighthouse: "The whole dome of heaven... was flecked with bars of misty light, revolving majestically on the axis of the tower." He said it was like a "magic lantern." Keepers like Charles W. Vanderhoop and his assistant Max Attaquin, reportedly took hundreds of thousands of visitors to the top between 1910 and 1933!

After the lighthouse was automated in the 1950s, it was closed to the public. But in 1986, VERI reopened it on Mother's Day. It became available for tours, special events, and even weddings. Charles Vanderhoop, Jr., who was born in the lighthouse, became an Assistant Keeper, following in his father's footsteps. School children from the island also started visiting as part of VERI's educational programs.

In 1994, VERI transferred the lighthouse license to the Martha's Vineyard Historical Society (now the Martha's Vineyard Museum). Today, the Gay Head Light is managed by the Martha's Vineyard Museum and is open to the public during the summer and for special events. In 2009, Principal Keeper Joan LeLacheur even gave President Barack Obama and his family a private tour! You can also briefly see the lighthouse in the background of the movie Jaws.

The Gay Head Light stands today as an important symbol of Martha's Vineyard's history, thanks to the hard work and dedication of the community.

New Ownership and Relocation (2011-2015)

In 2011, the Gay Head Light was considered for new ownership. The U.S. Coast Guard and General Services Administration (GSA) made it available to local governments, nonprofits, or even private buyers. The Martha's Vineyard Museum and the Town of Aquinnah (where the lighthouse is located) discussed taking over its care.

The National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act allows historic lighthouses to be transferred at no cost to groups that will preserve them. The Town of Aquinnah, with help from the Martha's Vineyard Museum, worked to gain ownership. They also raised money to help repair and maintain the light.

Due to ongoing erosion of the cliffs, the lighthouse was in danger of falling into the ocean. So, in May and June 2015, a huge project took place: the Gay Head Lighthouse was moved!

The lighthouse committee and the town of Aquinnah raised about $3.5 million to move the lighthouse about 129 feet (39 m) back from the cliff edge. Expert House Movers and International Chimney handled the move. They reinforced the inside of the lighthouse with cement blocks and steel beams. A special roadway was built, and the lighthouse was pushed along steel tracks using powerful pneumatic equipment.

The lighthouse needed to stay at the same height for its light signal to be correct. So, a new cement block foundation was built to raise it to the right level. This new foundation and the old granite one are now buried under soil. The light was turned off on April 16, 2015, for the move. It was relit on August 11, 2015, at 6:08 PM. The new location is about 180 feet from the cliff, and experts believe it will be safe for another 150 years!

List of Keepers

- Ebenezer Skiff (Principal Keeper 1799–1828)

- Ellis Skiff (Principal Keeper 1828–1845)

- Samuel H. Flanders (Principal Keeper 1845–1849 and 1853–1861)

- Henry Robinson (Principal Keeper 1849–1853)

- Ichabod Norton Luce (Principal Keeper 1861–1864)

- Calvin C. Adams (Principal Keeper July, 1864–1868)

- James O. Lumbert (Principal Keeper 1868–1869)

- Horatio N. T. Pease (Assistant Keeper 1863–1869, Principal Keeper 1869–1890)

- Frederick H. Lambert (Assistant Keeper c1870-1872)

- Calvin M. Adams (Assistant Keeper c1872-c1880)

- Frederick Poole (Assistant Keeper c1880-1884)

- Crosby L. Crocker (Assistant Keeper c1885-1892)

- William Atchison (Principal Keeper 1890–91)

- Edward P. Lowe (Principal Keeper 1891–1892)

- Crosby L. Crocker (Principal Keeper 1892–1920)

- Leonard Vanderhoop (Assistant Keeper, 1892-c1894)

- Alonzo D. Fisher – Crosby Crocker's son-in-law (Assistant Keeper 1894–?)

- William A. Howland, (Assistant Keeper, 1897–?)

- Charles Wood Vanderhoop (Principal Keeper 1920–1933)

- Max Attaquin (Assistant Keeper 1920 -1933)

- James E. Dolby (Principal Keeper 1933–1937)

- Frank A. Grieder (Principal Keeper 1937–1948)

- Sam Fuller (Assistant Keeper c.? 1940s)

- Arthur Bettencourt (Principal Keeper 1948–1950)

- Joseph Hindley (Principal Keeper 1950–1956)

- William Waterway Marks (Principal Keeper 1985–1998)

- Charles Vanderhoop, Jr. (Assistant Keeper 1985–1990)

- Helen Manning (Assistant Keeper 1985–1990)

- Robert McMahon (Assistant Keeper 1985–1990)

- Todd Follansbee (Assistant Keeper: 2010–2012)

- Richard Skidmore and Joan LeLacheur (Assistant Keepers 1990–98, Principal Keepers 1998–present)