Generation of '80 facts for kids

The Generation of '80 (in Spanish: Generación del '80) was a group of powerful leaders in Argentina. They were in charge from 1880 to 1916. These leaders came from rich families in the provinces and the capital city, Buenos Aires. They joined together to form a big political party called the National Autonomist Party. In 1880, General Julio Argentino Roca became president. He was a key leader of this group.

These leaders held important jobs in politics, business, the military, and even religion. They often stayed in power by using unfair elections. Despite growing opposition from groups like the Radical Civic Union and workers' movements, they remained in control. This changed with the Sáenz Peña Law. This law made voting secret, universal for men, and required. It marked a big step into modern Argentine history.

Contents

What the Generation of '80 Believed

The Generation of '80 continued the work of earlier presidents like Bartolomé Mitre, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, and Nicolás Avellaneda. They took advantage of a time when Argentina was more peaceful and economically stable. This led to a feeling of hope and belief in a bright future.

Their Main Ideas: "Order and Progress"

The politicians of this group believed in liberal economic ideas. This meant they wanted less government control over business. They also held socially conservative views, meaning they preferred traditional ways of life. A big part of their thinking was positivism. This idea focused on using science and reason to improve society. Their main motto was "Order and Progress."

They strongly believed in "progress," which for them meant economic growth and making the country more modern. They thought "order" was needed for this progress. They believed that a peaceful country would naturally lead to growth. President Julio Argentino Roca's actions were based on "Peace and Administration." This idea combined both liberal and conservative thinking.

For most of their time in power, these leaders believed Argentina was destined for endless progress. They wanted their country to grow in every way: economically, socially, culturally, and materially. They thought that if they created a stable environment, progress would happen naturally. Only during the Economic Crisis of 1890 was this belief questioned, but optimism soon returned.

Influences on Their Thinking

The Generation of '80 saw themselves as following the ideas of the Generation of '37. They adopted principles from important thinkers of that time. For example, they took ideas about culture and race from Juan Bautista Alberdi. They also adopted the idea of rejecting old traditions from Esteban Echeverría. The idea of "civilization versus barbarism" from Domingo Faustino Sarmiento was also very important to them.

Their positivist ideas were greatly shaped by Herbert Spencer. He applied Charles Darwin's ideas of evolution to how societies work. This became known as Social Darwinism, meaning "survival of the fittest." Following Sarmiento's ideas, they saw Gauchos and indigenous peoples as "barbarians." They believed these groups were not ready for a modern, "civilized" life.

They thought it was necessary to remove this "barbarism" through "order." This would strengthen "civilization." They believed that bringing in European people would help Argentina progress. They did not see a problem with their culture replacing native cultures. They thought European cultures were more "fit" for the modern world.

Church and State

The Generation of '80 also had disagreements with the Catholic Church. They wanted to create a clearer separation between the Church and the government. They passed laws for Civil Marriage, Civil Registry, and Public Education. The education law made primary school mandatory, free, and non-religious.

These changes showed they wanted to reduce the Church's influence in public life. However, they did not try to completely separate Church and State. These measures caused constant conflict with the Church. Some Catholic leaders within the Generation of '80, like José Manuel Estrada, questioned these anti-Church positions.

How the Economy Grew

The Generation of '80 brought a time of great economic growth to Argentina. They used a liberal economic policy focused on exporting farm products. This fit well with the new global trade system led by British merchants. Argentina focused its economic activity in the Pampas region. Its main port was Buenos Aires.

The country produced meat (from sheep and cattle), leather, wool, and grains like wheat and corn. Most of these products went to the British market. In return, Argentina imported industrial goods. For example, 95% of its exports were farm products. But it imported 77% of its textiles and 67% of its metal goods. At the same time, British money funded many of Argentina's services. These included banks, railways, and refrigeration.

In 1887, after his first presidency, Julio A. Roca visited London. He met with members of the British government. Roca described the relationship between Argentina and Great Britain this way:

I am perhaps the first former president from South America to have been the object in London of such a reception of gentlemen. I have always held a great sympathy towards England. The Argentine Republic, which will one day be a great nation, will never forget that the state of progress and prosperity that is found at this time is due in great part to English funding.

Experts estimate that by the early 1900s, half of Argentina's GDP came from imports and exports. In 1888, Argentina was the sixth-largest exporter of grains. By 1907, it was third, behind only the United States and Russia. Some people have criticized this economic model. They say it did not invest enough in other industries, like textiles or metal production.

The policy of exporting farm products was mainly supported by ranchers in the Province of Buenos Aires. These ranchers, called estancieros, formed the Rural Society of Argentina. This was the country's first workers' union, started in 1868. They stopped President Sarmiento's plan to give land to immigrants. Sarmiento wanted to create farms worked by their owners. President Avellaneda canceled this plan, keeping large ranches as the main system.

Even though they used free-trade economic policies, the government also supported State involvement. They believed the government should be involved in important areas. These included education, justice, and public works. They also expanded government services across the country.

How the Population Grew

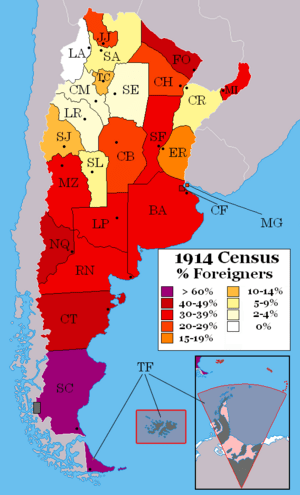

The Generation of '80 also oversaw a huge wave of European immigration to Argentina. Treaties with neighboring countries, like the one ending the Paraguyan War, helped secure Argentina's borders. This brought peace to the country. Europe, at the time, was often at war.

Argentina had a generous policy that encouraged immigration. This followed the rules in the Argentine Constitution. Millions of new people came into the country. However, this policy was partly limited by some strict laws. The 1902 Law of Residency and the 1910 Law of Social Defense were passed. These laws aimed to control the spread of socialism and anarchism among workers.

The huge growth in population led to workers' movements. These groups started demanding better living and working conditions. They often used strikes to pressure the government. About 25 years later, thanks to the policies of the Generation of '80, this wave of immigration led to a big social change. This change helped the Radical Party come to power.

The End of the Generation of '80's Power

During Julio A. Roca's second presidency, the Law of Residency was passed. This law allowed the government to quickly expel foreign activists who opposed the government. Roca's brother-in-law, Miguel Ángel Juárez Celman, had been overthrown in the Revolution of the Park in 1890. In 1905, the Radical Party started a coordinated uprising in several provinces. In 1910, during the 100-year celebration of the May Revolution, the Law of Social Defense was passed. This law allowed for the arrest of people suspected of being anarchists.

The government also made small efforts to calm workers' demands. For example, they created the National Department of Labor in 1907. So, the conservative government passed the first labor laws of that time. However, these laws were not enough. There was a huge growth in the number of workers due to immigration and economic expansion.

Facing growing demands from the middle class, constant strikes, and criticism from the press and Congress, the Generation of '80 had to respond. They were led by the modern part of the National Autonomist Party. They decided to allow more people to participate in politics. They passed the Sáenz Peña Law in 1912. This law made voting secret, universal, and mandatory for men over 18.

In 1916, the first elections under this new law took place. The conservative government lost the presidential elections for the first time. Power went to the radical Hipólito Yrigoyen. He became president with the support of most of Argentina's middle class.

What "Generation of '80" Means

The term "Generation of '80" first appeared in the 1920s. It originally referred to a group of writers. Over time, this term began to include politicians and thinkers of that era. Historians and writers like Manuel Mujica Láinez and Carlos Ibarguren helped spread its use.

Later, historians like David Viñas used the term to describe the rich, powerful leaders. These leaders were connected to cattle farming and followed the ideas of the earlier Generation of '37. By the 1970s, the term was widely used with this meaning. However, it can be tricky to decide exactly who belonged to this "generation." Some younger leaders and thinkers from the early 1900s had different ideas than their older predecessors.

See also

In Spanish: Generación del 80 para niños

In Spanish: Generación del 80 para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |