George Nuttall facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

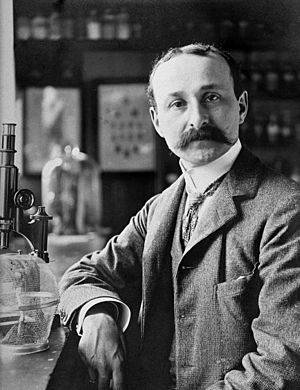

George Nuttall

|

|

|---|---|

George Nuttall in 1901

|

|

| Born |

George Henry Falkiner Nuttall

5 July 1862 |

| Died | 16 December 1937 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | British American |

| Alma mater | University of California (M.D.) University of Göttingen (Ph.D) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | bacteriology |

| Institutions | University of Cambridge |

George Henry Falkiner Nuttall (born July 5, 1862 – died December 16, 1937) was an American-British scientist. He studied bacteriology, which is the study of tiny living things called bacteria. He learned a lot about parasites and how insects can spread diseases.

Nuttall made important discoveries in how our bodies fight off sickness (called immunology). He also studied how life works in very clean, germ-free conditions. He learned about blood chemistry and diseases that are spread by arthropods, especially ticks. He even looked into where Anopheline mosquitoes lived in England. This helped explain why malaria used to be common there. With another scientist, William H. Welch, he found the germ that causes a serious infection called gas gangrene.

Contents

Life and Discoveries

George Nuttall was born in San Francisco, California, in 1862. His father was a British doctor. When George was three, his family moved to Europe. He went to school in England, France, Germany, and Switzerland. Because of this, he learned to speak German, French, Italian, and Spanish very well. This was a big help in his work later on.

In 1878, Nuttall came back to the United States. He earned his M.D. degree (which means he became a doctor) from the University of California, Berkeley in 1884. After that, he spent a year in Mexico with some of his family. His sister, Zelia Nuttall, became a famous expert on old Mexican cultures.

After working briefly at Johns Hopkins University, he went to Göttingen, Germany, in 1886. There, he studied how the body fights off sickness. He earned his PhD in zoology in 1890. He then returned to Baltimore and worked with William H. Welch. He helped identify the germ that causes gas gangrene, which is now known as Clostridium perfringens.

From 1892 to 1899, Nuttall was back in Germany. He worked at the Hygienic Institute in Berlin. In 1893, he wrote a book called Hygienic Measures in Relation to Infectious Diseases. This book was about keeping things clean, disinfecting, and fumigating in medicine.

In 1895, he married Paula von Oertzen-Kittendorf. He also worked on raising guinea pigs in a completely germ-free environment. This research helped start a new field of study called Gnotobiosis. This field looks at how animals live with known groups of tiny organisms. In 1895, he also designed a special device called a microscopic thermostat. It kept tiny living things at a steady temperature for study.

In 1899, Nuttall moved to Cambridge, England. He was invited to give talks about bacteriology at the University of Cambridge. In 1900, he became a university lecturer there. He stayed in Cambridge for the rest of his life. He started and edited the Journal of Hygiene, a science magazine, in 1901.

At this time, he studied blood and how it reacts to sickness. He also looked at how arthropods (like insects) spread diseases, especially malaria through mosquitoes. In 1904, Nuttall and his colleague Arthur Shipley became Fellows of the Royal Society. This is a very important honor for scientists. That same year, he helped start the first special course in tropical medicine in Cambridge.

In 1906, he became the first Quick Professor of Biology at Cambridge. This job focused on studying protozoology, which is about tiny, single-celled organisms. He built a large team that studied many types of parasites. A big part of their work was on piroplasmosis. This is a disease like malaria that is spread by ticks. It affects animals like dogs and sometimes humans.

In 1908, Nuttall started another science magazine called Parasitology. This helped make the study of parasites a field of science on its own. During World War I, he started studying lice. This was important because lice caused problems for soldiers. His research looked at how lice lived and how they spread diseases.

In 1919, Nuttall asked for money to create a special institute for parasite research. A couple named Percy and his wife donated a large sum of money. The Molteno Institute for Research in Parasitology opened in 1921, and Nuttall was its first director.

Nuttall wrote about 150 articles for science magazines. As he got older, he spent more time managing the institute and raising money. He published fewer papers. His wife, Paula, died in 1922. He retired from his professorship in 1931 and became an Emeritus Professor. He died suddenly in December 1937.

How Our Bodies Fight Sickness

In the 1880s, a scientist named Élie Metchnikoff saw that certain cells in animals, including white blood cells in humans, could "eat" bacteria and other foreign things. He thought this was how animals protected themselves from infections. This idea was new and debated at the time.

Another scientist, Josef von Fodor, showed that blood seemed to kill anthrax bacteria. But some people thought the blood was just trapping the bacteria, not destroying them.

Nuttall did many experiments with blood that couldn't clot. He clearly showed that blood could kill germs even without clotting. He also found that if blood was heated to 55°C (131°F), it lost its ability to kill germs.

These findings were very important. They helped create the idea of humoral immunity. This is the idea that there are things in our blood (like antibodies) that fight off sickness. This was different from Metchnikoff's idea, which focused on cells. At first, these two ideas seemed to be in competition. But soon, scientists realized that both cells and substances in the blood work together to protect us.

Understanding Animal Family Trees

Charles Darwin's theory of Evolution says that living things change over time. It also says that species that are related share a common ancestor. For a long time, scientists classified animals only by their physical appearance. This method had problems, especially when different animals looked similar but were not closely related. It also couldn't show how closely related animals were in a measurable way.

In 1897, a scientist named Rudolf Kraus discovered something called the precipitin reaction. This is when an antibody (a protein that fights germs) mixes with an antigen (a substance that causes the body to make antibodies). They form a solid clump. At first, scientists thought this reaction was very specific. But they soon found that while the original protein caused the strongest reaction, similar proteins from related animals could also cause a reaction, just a weaker one.

Nuttall used this discovery to create a way to measure how related animals were. He measured the amount of clump that formed. He used blood serum from many different animals. He showed that the strength of the immune reaction between species told him how closely they were related.

In a big book called Blood immunity and blood relationship, Nuttall and his team shared results from over 16,000 tests. They used blood from many types of animals, including those with backbones and those without. This work was the beginning of a field called molecular evolution. This field uses molecular information (like DNA and proteins) to understand how living things are related.

Insects and Other Arthropods Spreading Diseases

In 1900, Nuttall and Ernest Edward Austen wrote a book. It looked at all the evidence that Insects, Arachnids (like spiders and ticks), and Myriapods (like centipedes) could spread diseases. It also talked about the idea that mosquitoes spread malaria. Malaria used to be common in England, but by 1900, there were very few cases.

Nuttall and his team surveyed where Anopheles mosquitoes lived in England. They found that these mosquitoes were common in the same areas where malaria had been common before. This study was one of the first of its kind to use maps to show disease patterns. Nuttall and Arthur Shipley then published many papers on the structure and life of Anopheles mosquitoes. This was the most detailed study on the topic at that time.

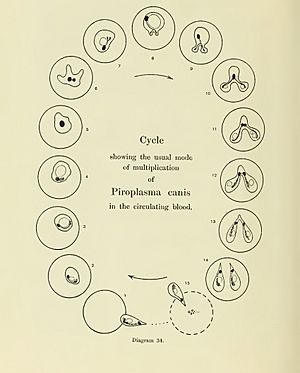

Nuttall started working on ticks and the diseases they spread in 1904. His first studies were on canine piroplasmosis. This disease, also called babesiosis, is like malaria. It's caused by a tiny protozoan parasite. At one point in its life, the parasite looks like a pear, which is why it's called piroplasmosis. It affects many wild and farm animals. Human cases are rare.

Scientists named Theobald Smith and Kilborne found the parasite in Texas cattle fever. They proved that ticks spread it. This was the first time it was proven that an arthropod could spread a disease. Nuttall and George Stuart Graham-Smith published many papers about canine piroplasmosis. They described the disease and how the parasite multiplied in the blood of dogs. Later, Nuttall and Seymour Hadwen found that a blue dye called trypan blue was a good treatment for the disease in dogs and cattle. This was a very important discovery for farmers, and trypan blue was used as a standard treatment for many years.

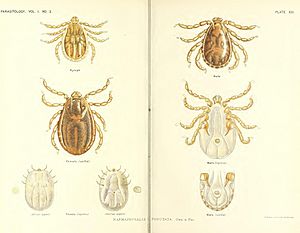

Nuttall also did many studies on ticks with other scientists. This led to many papers and a very detailed book about ticks. These publications covered the body parts of ticks, how they live, and how they are classified. They also included observations on the diseases ticks spread, like "tick paralysis." During this work, Nuttall collected a huge number of ticks from all over the world. This collection is now in the Natural History Museum, London.

Another arthropod that became very important during World War I was the louse. Nuttall studied lice in detail. Like many of his other studies, this work combined scientific understanding with practical solutions for problems caused by lice.

Parasites Named for Him

- Nuttallia — This name was given to a group of piroplasms. However, the name was already used for a type of clam. So, the group of piroplasms is now called Babesia.

- Nuttalliellidae — This is a family of ticks found in southern Africa. This family has only one species, Nuttalliella namaqua.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |