Giant cuttlefish facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Giant cuttlefish |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Giant cuttlefish from Whyalla, South Australia | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Sepiida |

| Family: | Sepiidae |

| Genus: | Sepia |

| Subgenus: | Sepia |

| Species: |

S. apama

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sepia apama Gray, 1849

|

|

|

|

| Distribution of Sepia apama | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

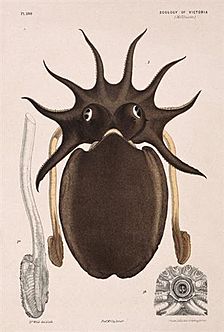

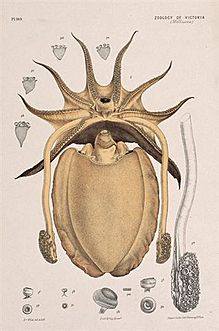

The Giant Cuttlefish (scientific name Sepia apama) is also known as the Australian Giant Cuttlefish. It is the biggest cuttlefish species in the world! These amazing creatures can grow up to 50 centimeters (20 inches) long in their main body (called the mantle). Their total length, including their long tentacles, can reach 100 centimeters (about 3.3 feet). They can weigh over 10.5 kilograms (23 pounds).

Giant Cuttlefish are masters of disguise. They use special cells called chromatophores to change their color and patterns instantly. This helps them blend in with their surroundings or put on dazzling displays. You can find them in the cool and warm waters around Australia. They live from Brisbane in Queensland all the way to Shark Bay in Western Australia, and south to Tasmania. They like rocky reefs, seagrass beds, and sandy or muddy seafloors, living up to 100 meters (330 feet) deep. In 2009, they were listed as "Near Threatened" because their numbers seemed to be going down.

Contents

Lifecycle and Reproduction

Giant Cuttlefish usually live for only one to two years. They breed when winter starts in the southern parts of Australia. During this time, males stop trying to hide and instead show off with bright, quickly changing colors and patterns. They do this to impress the females. Females often mate with more than one male.

Females lay their eggs under rocks in caves or hidden spots. The eggs hatch after about three to five months. Giant Cuttlefish only breed once in their lives. After they lay their eggs, they die soon after. This is because they don't eat much during the breeding season. They slowly lose energy and condition until they pass away.

Across Australia, these cuttlefish usually breed in pairs or small groups. They lay their eggs in caves or cracks in rocks. Sometimes, small groups of up to 10 cuttlefish gather to spawn. But there's one very special place: hundreds of thousands of them gather along rocky reefs between Whyalla and Point Lowly in the Upper Spencer Gulf. After the baby cuttlefish hatch, they leave these breeding areas. Scientists don't know much about where they go or what they do as juveniles. Adult cuttlefish return to these special breeding spots the next winter, or sometimes the year after.

Amazing Abilities and What They Eat

Giant Cuttlefish are amazing hunters. They are carnivores, meaning they eat meat. They are also opportunistic, which means they will eat whatever food they can find. They mostly eat crustaceans like crabs and shrimp, and also fish.

These cuttlefish have incredible control over their skin. They use special cells called chromatophores (which are red to yellow), iridophores (which create shiny, rainbow-like colors), and leucophores (which are white). These cells allow them to change their color and patterns in less than a second! The cells are in three layers under their skin. Leucophores are at the bottom, and chromatophores are on top. By blocking certain colors, these layers work together to create cool patterns, even polarized ones.

Unlike most animals, cuttlefish iridophores can actively change how much light they reflect. They can also control how much light is polarized. Cuttlefish are colorblind, but their eyes are set up in a way that lets them see the linear polarization of light. This means they can see light waves that vibrate in a specific direction. While mantis shrimp are known for true polarization vision, cuttlefish might also use it. Since their brain parts for vision are very large, and their skin makes polarized patterns, they might even use this vision to communicate with each other!

Giant Cuttlefish can also change the shape and texture of their skin. They can raise bumps called papillae to look like rocks, sand, or seaweed. This helps them hide from predators.

Studies show that Giant Cuttlefish are mostly active during the day. They don't move around much, usually staying within a small area. But they travel long distances to breed. They spend about 95% of their day resting. This means they save a lot of energy for growing. They spend very little time hunting for food. The only time they are much more active is during the mass breeding gathering.

Who Eats Giant Cuttlefish?

The Australian Giant Cuttlefish is a tasty meal for some other ocean animals. Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins have been seen eating them in South Australia's Spencer Gulf. These clever dolphins have even learned how to remove the ink and the hard cuttlebone before eating the cuttlefish! Long-nosed fur seals also enjoy eating them. Yellowtail kingfish are also known to eat cuttlefish. This has caused some worry that kingfish escaping from fish farms might eat the young cuttlefish or their eggs in Spencer Gulf.

The Special Upper Spencer Gulf Population

Scientists have found that there are several groups of Giant Cuttlefish in Australia that don't interbreed much. The group in the upper Spencer Gulf is the most studied. This is because it's the only known place in the world where so many cuttlefish gather to breed! It has also become a very popular spot for divers and snorkelers to visit.

Hundreds of thousands of Giant Cuttlefish gather on the reefs near Point Lowly, close to Whyalla, between May and August. Outside of breeding season, there are usually equal numbers of males and females. But during the breeding gathering in Spencer Gulf, there can be up to 11 males for every female! Scientists are not sure if this is because fewer females come, or if males breed for a longer time.

The sheer number of cuttlefish here is amazing. There can be one cuttlefish per square meter, covering an area of about 61 hectares (150 acres). While they are breeding, the cuttlefish don't seem to notice divers at all. This makes them a huge attraction for tourists from all over the world. Professor Roger Hanlon from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution has called this breeding gathering "the premier marine attraction on the planet."

The cuttlefish in the upper Spencer Gulf have two different life paths. Some grow quickly, becoming adults in seven to eight months, and return to breed in their first year. Others grow slowly, taking two years to mature, and return to breed in their second year as larger adults. Because so many cuttlefish gather here, they have developed unique breeding behaviors. Large males protect females and egg-laying spots. Smaller males, called "sneakers," pretend to be females to get close to the females being guarded by the big males.

Protecting the Cuttlefish

There have been efforts to protect this special group of Giant Cuttlefish. People were worried about their numbers going down and the risk of pollution from nearby industries. In 2011, an application was made to list them as a threatened species. However, it was decided that this group was not different enough from other Giant Cuttlefish for the law to protect them separately. Still, new scientific work suggests they are genetically different from other groups.

Fishing for Cuttlefish

Before the mid-1990s, the upper Spencer Gulf cuttlefish were caught for snapper bait. About 4 tonnes (4,000 cuttlefish) were caught each year. But in 1995 and 1996, commercial fishing on the breeding grounds caught around 200 tonnes each year. This was too much. In 1997, 245 tonnes were caught, which was recognized as overfishing. So, in 1998, half of the breeding grounds were closed to commercial fishing. Even with the closure, 109 tonnes were caught in 1998. The catch then dropped to 3.7 tonnes in 1999.

| Financial Year | Tonnes caught |

|---|---|

| 1992–93 |

3

|

| 1993–94 |

7

|

| 1994–95 |

35

|

| 1995–96 |

71

|

| 1996–97 |

263

|

| 1997–98 |

170

|

| 1998–99 |

15

|

| 1999–00 |

16

|

| 2000–01 |

19

|

| 2001–02 |

27

|

| 2002–03 |

11

|

| 2003–04 |

6

|

| 2004–05 |

9

|

| 2005–06 |

8

|

| 2006–07 |

11

|

| 2007–08 |

6

|

| 2008–09 |

4

|

| 2009–10 |

10

|

| 2010–11 |

5

|

| 2011–12 |

3

|

| 2012–13 |

4

|

| 2013–14 |

2

|

Why Did Numbers Decline?

From 1998 to 2001, the number of cuttlefish seemed stable because fishing was reduced. But in 2005, a survey showed a 34% drop since 2001. This was thought to be due to natural changes and illegal fishing. The closed fishing area was then made larger. While numbers seemed to increase in 2006 and 2007, a new survey in 2008 found another 17% decrease.

In 2011, only about 33% of the 2010 population returned to breed. This was fewer than 80,000 cuttlefish. Local fishermen said that a small area outside the closed zone was being targeted by commercial fishers. They believed this stopped the cuttlefish from reaching their breeding grounds. Since cuttlefish only breed once, scientists were very worried about their survival.

In 2012, the numbers dropped again. A special group was formed to investigate why. A tour guide named Tony Bramley, who had been taking divers to see the cuttlefish for years, said it was "heartbreaking" to see how few were left. He remembered a time when there were so many cuttlefish you couldn't land on the seafloor without pushing them aside.

The Conservation Council of South Australia warned that the Spencer Gulf cuttlefish could become extinct in a few years if nothing was done. They believed this group was a separate species. The government working group suggested an immediate ban on fishing for cuttlefish. However, this was rejected in September 2012. The Fisheries Minister, Gail Gago, said there was no strong proof that fishing was causing the decline.

On March 28, 2013, the government put a temporary ban on fishing for cuttlefish in the northern Spencer Gulf for that breeding season. Minister Gago said research had ruled out commercial fishing as the cause, but the real reason was still unknown. The population continued to drop, reaching the lowest numbers ever in 2013.

Good news came in 2014, when the cuttlefish population showed signs of recovery after 15 years of decline. Numbers increased again in 2015, confirming this positive trend. By 2021, the population had recovered to an estimated over 240,000 animals!

The fishing ban for the whole of northern Spencer Gulf was extended until 2020. This stopped fishing in all Spencer Gulf waters north of Wallaroo and Arno Bay. In 2020, the closed area became smaller, covering only False Bay, from Whyalla to Point Lowly, and north towards the Point Lowly North marina.

Population Estimates

| Year | Population estimate |

|---|---|

| 1999 |

168,497

|

| 2000 |

167,584

|

| 2001 |

172,544

|

| 2002 |

0

|

| 2003 |

0

|

| 2004 |

0

|

| 2005 |

124,867

|

| 2006 |

0

|

| 2007 |

0

|

| 2008 |

75,173

|

| 2009 |

123,105

|

| 2010 |

104,805

|

| 2011 |

38,373

|

| 2012 |

18,531

|

| 2013 |

13,492

|

| 2014 |

57,317

|

| 2015 |

130,771

|

| 2016 |

177,091

|

| 2017 |

127,992

|

- Figure '0' means no survey was done that year.

- Data from 1999–2017 comes from the SARDI.

Impact of Local Industries

The large cuttlefish breeding sites in the Upper Spencer Gulf are close to several industrial areas. These industries release pollution into the sea. Some of the main concerns for cuttlefish are changes in salinity (saltiness) from desalination plants and too many nutrients from other discharges.

Nutrient Pollution

The northern Spencer Gulf naturally has low levels of nutrients. But pollution from industries can add too many nutrients, which can harm the cuttlefish and the environment. The Whyalla steelworks, for example, releases ammonia into the gulf. Fish farming, which happened nearby until 2011, also added nutrients from uneaten food and fish waste. Some people noticed that when fish farming increased, cuttlefish numbers went down. When fish farming stopped, the cuttlefish numbers recovered.

Oil and Gas Pollution

In 1984, a hydrocarbon processing plant was built at Port Bonython, near the breeding grounds. There have been worries about how this plant might affect the cuttlefish. There were two major pollution events there. One was groundwater contamination, and the other was an oil spill in 1992, where 300 tonnes of crude oil spilled into the sea. The effects of these events on the cuttlefish are not fully known.

Desalination Plants

Scientists and the community have been concerned about the salty water (brine) released from seawater desalination plants. These plants remove salt from seawater to make fresh water. In the 2000s, a company planned to build a large desalination plant near the breeding grounds. It would have released a lot of very salty water each day. Cuttlefish embryos (baby cuttlefish) don't develop well and die if the water is too salty. So, there was a lot of public opposition. The plan was approved in 2011 but was never built. Since then, two smaller desalination plants have been built and release brine into the gulf.

In 2022, a new, large desalination plant project was proposed. Its possible locations are all in the upper Spencer Gulf, which brings back worries for the cuttlefish.

Port Proposals

Because of nearby ore deposits, some mining companies want to build a large port at Port Bonython, next to Point Lowly. A new wharf for loading iron ore has been proposed. Community groups have formed to oppose new desalination and port developments near the cuttlefish breeding habitat. In 2021, a new port was approved at the site of former power stations. More shipping traffic in the upper Spencer Gulf could also affect cuttlefish, as they are sensitive to loud, low-frequency sounds.

See also

In Spanish: Sepia apama para niños

In Spanish: Sepia apama para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |