Gotse Delchev facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Voivode

Gotse Delchev

|

|

|---|---|

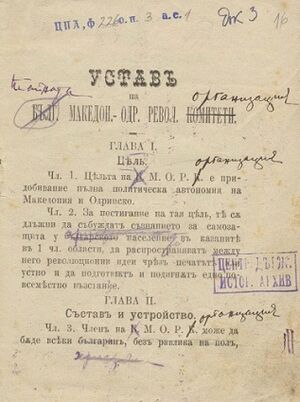

Portrait of Gotse Delchev in Sofia c. 1900

|

|

| Native name |

Гоце Делчев

|

| Birth name | Georgi Nikolov Delchev (Георги Николов Делчев) |

| Born | 4 February 1872 Kukush, Salonica Vilayet, Ottoman Empire (now Kilkis, Greece) |

| Died | 4 May 1903 (aged 31) Banitsa, Salonika Vilayet, Ottoman Empire (now Greece) |

| Buried | |

| Service/ |

Bulgarian army Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (later SMARO, IMARO, IMRO) Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee |

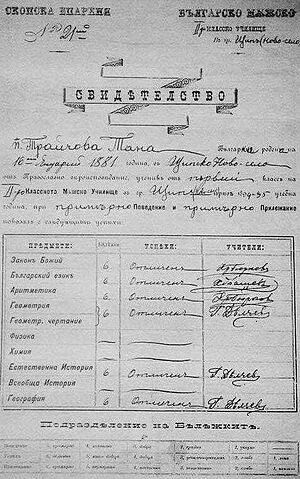

| Alma mater | Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki Military School of His Princely Highness |

| Other work | Teacher |

Gotse Delchev (born Georgi Nikolov Delchev; 4 February 1872 – 4 May 1903) was a very important revolutionary from the Macedonia and Adrianople regions. These areas were part of the Ottoman Empire at the time.

Gotse Delchev was a main leader of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). This was a secret group that worked to free these lands from Ottoman rule. He was a representative of the organization in Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria. He also joined the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC). Gotse Delchev was killed in a fight with Ottoman soldiers just before a big uprising began.

He was born into a Bulgarian family in Kilkis, which is now in Greece. As a young man, he was inspired by earlier Bulgarian heroes like Vasil Levski. These heroes dreamed of a Bulgarian republic where everyone was equal. Delchev studied at the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki. Later, he went to a military school in Sofia. However, he was dismissed because of his political views. After that, he returned to Ottoman Macedonia as a teacher. He quickly joined the new revolutionary movement in 1894.

Gotse Delchev believed in the idea of "Macedonia for the Macedonians." This meant that all different groups living in the area should work together. His goal was to create an independent state for Macedonia and Adrianople within the Ottoman Empire. He hoped this would lead to a larger Balkan Federation. He changed the rules of the organization so that people from all ethnic groups could join. This showed how much he believed in cooperation.

Today, Gotse Delchev is seen as a national hero in both Bulgaria and North Macedonia. In North Macedonia, some say he helped start the Macedonian national movement. However, Delchev himself clearly identified as Bulgarian. He believed his people were Bulgarians. His ideas for an independent Macedonia helped lead to the later development of Macedonian nationalism.

Contents

Gotse Delchev's Life

Early Years and Education

Gotse Delchev was born on February 4, 1872, in Kilkis, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire. Kilkis was a center for the Bulgarian national revival movement. Gotse first went to a Bulgarian primary school. He also read many revolutionary books in the town's library. These books made him dream of freeing Bulgaria.

In 1888, his family sent him to the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki. There, he started a secret revolutionary group. He also shared revolutionary books that he got from friends who studied in Bulgaria. After high school, he decided to join the military school in Sofia in 1891. He was full of hope for the newly independent Bulgaria. However, he soon became disappointed with the politics there.

Gotse spent his free time with people who had moved from Macedonia. Many of them were part of the Young Macedonian Literary Society. Through these friends, he learned about new ways to fight for social change. In 1892, Delchev met Ivan Hadzhinikolov, who wanted to create a revolutionary group in Ottoman Macedonia. They agreed on how to start this organization. Delchev promised to join after he finished military school.

In September 1894, just a month before he was supposed to graduate, he was expelled. This happened because he was part of an illegal socialist group. He refused to rejoin the army. Instead, he went back to the Ottoman Empire to work as a Bulgarian teacher. He wanted to join the new movement for freedom. At that time, the IMRO was just starting. It was forming groups around the Bulgarian schools.

Becoming a Revolutionary Leader

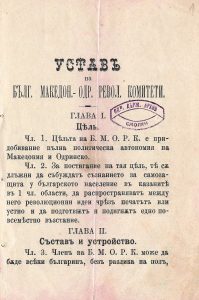

In 1893, a revolutionary group was founded in Thessaloniki. It was started by a few Bulgarian revolutionaries who wanted to fight the Ottomans. This group was first called the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (BMARC). In 1902, its name changed to the Secret Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (SMARO).

In the autumn of 1894, Delchev became a teacher in Štip. There, he met another teacher, Dame Gruev, who was a leader of the new local BMARC group. Delchev joined the organization right away. He quickly became one of its most important leaders. Both Gruev and Delchev worked together in Štip. The organization grew quickly. It set up groups across Macedonia and the Adrianople Vilayet, often based in Bulgarian schools.

Delchev traveled during his holidays. He set up new groups in villages and cities. He also met with leaders of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC). This group wanted freedom for Macedonia and Thrace. However, many SMAC leaders were officers who wanted to start a war. They hoped this would lead to Bulgaria taking over these areas. Delchev did not agree with their methods.

In May 1896, Ottoman authorities arrested Delchev. They suspected him of revolutionary activity. He spent about a month in jail. Later, he attended a meeting of the BMARC in Thessaloniki. After this, he quit his teaching job. In the autumn of 1896, he moved back to Bulgaria. There, he and Gyorche Petrov became representatives of the organization in Sofia. They helped the group get support from the Bulgarian government and army.

Leading the Organization

Delchev's involvement was a key moment for the Macedonian-Adrianople freedom movement. From late 1896 until his death in 1903, he was very active. Between 1897 and 1902, he was a representative of the BMARC in Sofia. He often felt frustrated by the politicians and arms dealers he met there.

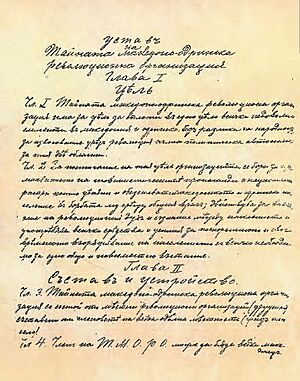

In 1897, he and Gyorche Petrov wrote new rules for the organization. These rules divided Macedonia and Adrianople into seven regions. Each region had its own structure and secret police. In 1898, Delchev decided to create permanent armed groups called chetas in each area. From 1902 until his death, he led these chetas. He was very skilled in military matters. Delchev also made sure that weapons and supplies could be secretly moved across the border between Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire.

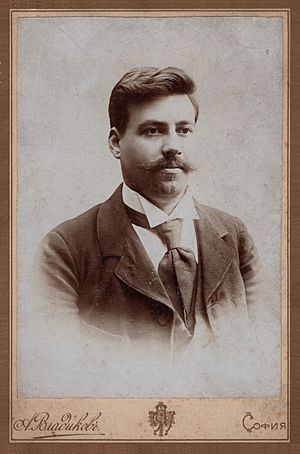

Delchev wanted the organization to make its own weapons. In 1897, he traveled to Odessa to learn about making bombs from Armenian revolutionaries. This led to a bomb factory being set up in Bulgaria. The bombs were then smuggled into Macedonia. Gotse Delchev also organized groups to rob or kidnap wealthy Turks. This helped the organization get money. He was also involved in the Miss Stone Affair, where an American missionary was kidnapped for ransom.

In 1900, he visited Burgas and set up another bomb factory. The dynamite from this factory was later used in the Thessaloniki bombings of 1903. He also checked on the BMARC groups in Eastern Thrace. He wanted to make sure the Macedonian and Thracian groups worked well together. From late 1901 to early 1902, he traveled throughout Macedonia. He inspected all the revolutionary areas. He also led a meeting of the Adrianople revolutionary district in Plovdiv in April 1902. Delchev was the military advisor and chief of all the internal revolutionary groups.

After 1897, many secret officer groups grew quickly. Many of their members joined the BMARC. Gotse Delchev supported their activities. He also wanted better cooperation between BMARC and the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee. For a short time, Delchev and Gyorche Petrov were part of the Supreme Committee's leadership. However, the Supreme Committee later split into two groups. Delchev did not like how some officers tried to control the BMARC. Sometimes, the SMAC even fought against local SMARO groups. In 1902, the SMAC organized an uprising that failed. This led to Ottoman attacks and hurt the SMARO's work.

There were disagreements about when to start the uprising in Macedonia and Thrace. At a meeting in Thessaloniki in January 1903, it was decided to start an uprising in the spring. Delchev did not attend this meeting. This led to big arguments at the SMARO conference in Sofia in March 1903. Some believed that a general uprising would make Bulgaria declare war on the Ottomans. They thought this would lead to other powerful countries getting involved and the Ottoman Empire falling apart.

Delchev wanted to create a secret network to prepare people for an armed uprising. He was against a large-scale uprising in the summer of 1903. He preferred smaller, more focused attacks. He was influenced by Bulgarian anarchists. He eventually agreed to the uprising but managed to delay it from May to August. Delchev also convinced the SMARO leaders to change the plan. Instead of a mass uprising involving everyone, it would be a fight based on guerrilla warfare.

In late March 1903, Gotse and his group destroyed a railway bridge. This was to test the new guerrilla tactics. After that, he went to Thessaloniki to meet Dame Gruev, who had just been released from prison. They talked about the decision to start the uprising. Delchev also met with Ivan Garvanov, who was then the leader of the SMARO. After these meetings, Delchev headed towards Mount Ali Botush. He was supposed to meet with groups from the Serres Revolutionary District. But he never arrived.

Death and Its Aftermath

On April 28, 1903, a group called the Gemidzii started terrorist attacks in Thessaloniki. As a result, the city was put under military rule. Many Ottoman soldiers were sent to the area. This led to Delchev's group being found. He died on May 4, 1903, in a fight with Turkish police near the village of Banitsa. It is thought that local villagers might have betrayed him. This happened while he was preparing for the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising. The movement lost its most important organizer just before the uprising began.

After being identified, Delchev and his friend, Dimitar Gushtanov, were buried in a shared grave in Banitsa. Soon after, the SMARO, with help from SMAC, started the uprising against the Ottomans. It had some early successes but was eventually crushed. Two of Delchev's brothers, Mitso and Milan, also died fighting the Ottomans. In 1914, the Bulgarian Tsar Ferdinand I gave a lifelong pension to their father, Nikola Delchev. This was to honor his sons' contributions to the freedom of Macedonia.

During the Second Balkan War in 1913, Kilkis was taken by Greece. Most of its Bulgarian people, including Delchev's family, were forced to move to Bulgaria. The same happened to the people of Banitsa, where Delchev was buried. During the Balkan Wars, when Bulgaria controlled the area, Delchev's remains were moved to Xanthi. After Western Thrace became part of Greece in 1919, his remains were brought to Plovdiv. In 1923, they were moved to Sofia, where they stayed until after World War II.

During World War II, Bulgaria again controlled the area. Delchev's grave near Banitsa was restored. In May 1943, a memorial plaque was placed in Banitsa. His sisters and other important people were there. Until the end of World War II, Delchev was seen as one of the greatest Bulgarians in the region of Macedonia.

The first book about Delchev's life was written in 1904 by his friend, the Bulgarian poet Peyo Yavorov. A detailed book about him in English is "Freedom or Death: The Life of Gotse Delchev" by Mercia MacDermott.

Gotse Delchev's Ideas

Gotse Delchev had a famous saying: "I understand the world solely as a field for cultural competition among the peoples." This shows his broad, international views. In the late 1800s, anarchists and socialists in Bulgaria connected their fight with revolutionary movements in Macedonia and Thrace. As a young student in Sofia, Delchev joined a left-wing group. He was greatly influenced by the ideas of Marxist and Bakunin.

His ideas were also shaped by earlier fighters against the Ottomans, like Vasil Levski and Hristo Botev. These men helped found important Bulgarian revolutionary groups. Delchev later joined the Internal organization. He was a well-educated leader and helped write the BMARC's rules in 1896.

In 1902, Delchev and other left-wing members changed the organization's rules. Before, only Bulgarians could be members. The new rules made it open to all people from Macedonia and Thrace, no matter their background. The organization was renamed the Secret Macedono-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Organization (SMARO). This group aimed for freedom for everyone in the region.

This idea was partly helped by the Treaty of Berlin (1878). This treaty gave Macedonia and Adrianople back to the Ottoman Empire. But it also promised future freedom for Christian people in those areas. An "independent status" meant the region would have its own special government and police.

However, the IMRO's idea of freedom was not always clear. Delchev and other left-wing activists had a general idea of how the future independent Macedonia and Adrianople would connect with Bulgaria. Some even thought that Bulgaria might join an independent Macedonia, rather than the other way around. Delchev, who believed in a republic, likely wanted to see the region join a future Balkan Federation.

At Delchev's time, the idea of a separate Macedonian nation and language was only supported by a few thinkers. It did not have wide support. The idea of freedom was mainly political. It did not mean separating from Bulgarian identity. For Delchev and others, freedom meant "radical political freedom by shaking off social chains." There is no sign that he doubted the Bulgarian identity of the Slavic people in Macedonia. Delchev also used the standard Bulgarian language. He was not interested in creating a separate Macedonian language.

Many international experts and even some Macedonian historians agree that Delchev identified as Bulgarian. However, despite his loyalty to Bulgaria, he was against any extreme nationalism. He believed that no outside power could help the organization. It had to rely only on itself. He thought that if Bulgaria got involved, other neighboring countries would too. This could lead to Macedonia and Thrace being torn apart. That is why the people of these two regions had to win their own freedom. This freedom would be within the borders of an independent Macedonian-Adrianople state.

Despite efforts by historians in North Macedonia after 1945 to show Delchev as a Macedonian separatist, Delchev himself said: "...We are Bulgarians and all suffer from one common disease [Ottoman rule]" and "Our task is not to shed the blood of Bulgarians, of those who belong to the same people that we serve."

Gotse Delchev's Legacy

Today, Gotse Delchev is seen as an important national hero in both Bulgaria and North Macedonia. Both nations see him as part of their own history. His memory is especially honored in the Bulgarian part of Macedonia. He is seen as the most important revolutionary from the second generation of freedom fighters. His name is also in the national anthem of North Macedonia: "Denes nad Makedonija".

Two towns are named after him: Gotse Delchev in Bulgaria and Delčevo in North Macedonia. There are also two mountain peaks named after him: Gotsev Vrah on Slavyanka Mountain, and Delchev Vrah or Delchev Peak in Antarctica. Delchev Ridge on Livingston Island also carries his name. The Goce Delčev University of Štip in North Macedonia is also named after him. Today, many items related to Delchev are kept in museums in Bulgaria and North Macedonia.

During the time of SFR Yugoslavia, a street in Belgrade was named after Delchev. In 2015, some Serbian nationalists covered the street signs. They put up new signs with the name of a different activist. They said Delchev was Bulgarian and his name should not be there. In 2016, the street's name was officially changed to Fyodor Tolbukhin. This was because they believed Delchev was not an ethnic Macedonian revolutionary. They saw him as part of an anti-Serbian group that supported Bulgaria.

In Greece, Bulgarian requests to put a memorial plaque where he died have not been answered. Memorial plaques put up by Bulgarians are often removed. Bulgarian tourists are sometimes stopped from visiting the place.

Memorials

-

Monument in Gotse Delchev, Bulgaria.

-

Monument in Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria.

-

Statues of Gotse Delchev and Dame Gruev in Skopje, North Macedonia.

-

The tomb of Gotse Delchev in the church Sv. Spas in Skopje, North Macedonia

Images for kids

-

Bulgarian postcard (1904) representing Delchev and an IMARO cheta. The inscription above reads: "The immortal Delchev."

-

The first biographical book about Delchev, issued in 1904 by his friend, the Bulgarian poet and revolutionary Peyo Yavorov.

See also

In Spanish: Gotse Delchev para niños

In Spanish: Gotse Delchev para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |