Grand Crimean Central Railway facts for kids

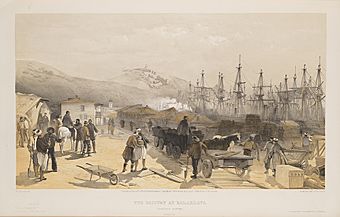

Main street of Balaclava showing the railway, painting by William Simpson

|

|

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Balaklava |

| Locale | Crimea, Russian Empire (Allied occupation zone) |

| Dates of operation | 1855–1856 |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) |

| Length | 14 miles (23 km) |

The Grand Crimean Central Railway was a special military railway built in 1855. It was created by Great Britain during the Crimean War.

Its main job was to carry supplies like ammunition and food. These were for the Allied soldiers fighting in the Siege of Sevastopol. The soldiers were on a high plateau between Balaklava and Sevastopol. This railway also carried what many believe was the world's first hospital train.

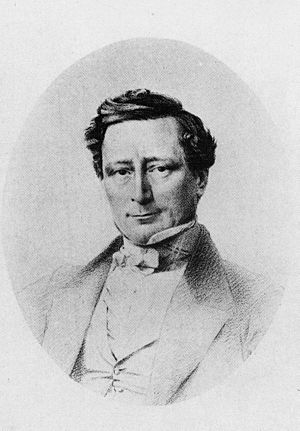

The railway was built quickly by a group of English railway builders called Peto, Brassey and Betts. They were led by Samuel Morton Peto. They built it without a contract and only charged for the costs. Just three weeks after their ships arrived with materials, the railway started running. In seven weeks, about 7 miles (11 km) of track was finished. This railway was very important for the Allies to win the siege. After the war ended, the tracks were sold and taken away.

Contents

Why Was the Railway Needed?

The Crimean War Begins

Britain and France declared war on Russia in March 1854. They did this to support the Ottoman Empire. By late 1854, the British, French, and Turkish allies decided to attack the Russian port of Sevastopol. They hoped this siege would end the war.

The British set up their main base in the small harbor of Balaklava. This was about 8 miles (13 km) south of Sevastopol. Most of the land between Balaclava and Sevastopol was a high plateau. The only road connecting them was very rough. It was hard to move supplies.

Winter Challenges and Supply Problems

In October, British troops struggled to move supplies and cannons up the road. They needed to prepare for the siege. The first big attack happened on October 17. Everyone thought the siege would be short, ending before winter.

But the Russians fought back well. They repaired damage quickly. The British soon ran low on ammunition and other supplies. Winter was coming, and bad weather made the road almost impossible to use. Supplies piled up at Balaclava. But they could not reach the soldiers. Many soldiers became sick from disease, frostbite, and lack of food.

A Solution: The Railway Idea

News of these terrible conditions reached Britain. A newspaper reporter named William Howard Russell shared the stories. Samuel Morton Peto, a famous railway builder, heard the news. He offered to build a railway to move supplies. His partners, Edward Betts and Thomas Brassey, joined him. They promised to build it quickly and only charge for the costs.

The British government accepted their offer. The builders quickly gathered supplies. They bought or rented ships and hired workers. These workers included skilled specialists and navvies (railway construction workers). Nine ships carried all the railway materials and about 500 workers. They brought rails, wooden sleepers, timber, and many tools. Each ship had a surgeon. The fleet left England in December and arrived in Crimea in early February.

Building the Railway

James Beatty was hired as the chief engineer. Donald Campbell surveyed the land for the track. Campbell's first job was to build a wharf at Balaclava. This was where railway materials could be unloaded.

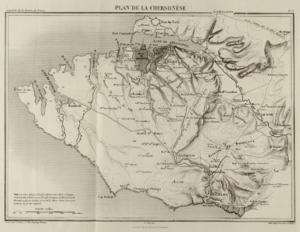

The plan was for the track to go through the main street of Balaclava. Then it would pass through a narrow gorge and over swampy ground to Kadikoi village. From Kadikoi, the railway had to climb about 500 feet (152 m) to the plateau. Campbell found a route that was not too steep. But it still needed a special engine at the top to pull carriages up. Once on the plateau, the ground was easier. A supply depot was built near Lord Raglan's headquarters.

By February 8, 1855, workers were laying the first rails in Balaclava. This was less than a week after they landed. By February 19, the railway reached Kadikoi. On February 23, the railway started moving supplies. Horses pulled the carriages from Balaclava to Kadikoi. This was only three weeks after the ships arrived.

The railway yard in Balaclava grew bigger. Buildings were put up for workers and to store materials. By March 26, the line reached the top of the plateau. The first load of supplies arrived at the headquarters. In less than seven weeks, about 7 miles (11 km) of track was laid. During this time, a famous photographer named Roger Fenton took pictures of the railway being built.

How the Railway Helped

Making a Difference

On April 2, the railway was used to carry sick and injured soldiers. They were moved from the plateau down to Balaclava. Many people believe this was the first hospital train ever.

The railway meant that enough supplies and weapons reached the soldiers. This allowed the Allies to attack again. The Second Bombardment started on April 9. The Russians still fought hard, but they lost many soldiers. The Allies also cut off a main Russian supply line in May.

More ammunition arrived by railway. This allowed the Allies to launch the Third Bombardment on June 6. This attack was much stronger. It was followed by an assault on June 7 and 8. The railway kept bringing supplies for more attacks.

The Siege Ends

The Russians suffered a big defeat in the Battle of the Tchernaya on August 16. The Fifth Bombardment began on August 17. Its goal was to destroy Russian defenses. The Sixth Bombardment led to a successful Allied attack on September 8. This finally ended the siege two days later.

During the summer, plans were made to supply not just the British, but also their French and Sardinian allies. Sardinia had joined the war in late 1854. Also, during this time, electric telegraphy was first used in war. An underwater cable connected Crimea to the Allies' base in Varna, Bulgaria.

Locomotives and New Lines

Locomotives (train engines) were brought in. The first one ran on November 8. But this was too late to change the outcome of the siege. The locomotives were not very good at climbing the steep hills. Five used locomotives arrived from England.

James Beatty, the chief engineer, left Crimea in November because he was sick. Donald Campbell took over. A special ship called Chasseur arrived to help with engineering work. Because the railway was built so fast, it was in danger of being damaged by winter weather. William Doyne helped build new, stronger lines very quickly. By November 10, about 6.5 miles (10 km) of track was laid between Balaclava and the British headquarters. Lines to the Sardinian and French headquarters were also built.

The War Ends

During the second winter, the railway carried different supplies. The siege was over, so less ammunition was needed. Instead, the railway brought huts to replace tents, clothing, food, books, and medical supplies for the soldiers.

The railway eventually reached its full length. It was about 14 miles (23 km) long, plus extra tracks for sidings.

Sevastopol was in ruins after the siege. The Russian leader, Tsar Nicholas I, died in March 1855. His son, Alexander II, started peace talks. The fighting stopped on February 29, 1856. The Treaty of Paris was signed on March 30, 1856. After the war, the Russians sold the railway tracks to the Turks. The rails were taken up, and the railway was gone.

The Argentina Myth

There is a popular story that says two steam engines from the Crimean railway went to Argentina. The story claims they were used on the new Buenos Ayres Western Railway. This myth also suggests that many railways in Argentina were built to a special wide gauge (1,676 mm (5 ft 6 in)) because of these engines.

However, research in the 1950s showed this story is not true. Records show the Crimean railway used a standard gauge (1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in)). The two Argentine engines, "La Porteña" and "La Argentina," were built in 1856. This was after the Crimean railway was already being taken apart. Also, these engines would not have worked well on the steep hills in Balaclava. They also could not have been easily changed from standard to broad gauge.

However, some old reports do mention engines from the Crimean War going to Argentina. For example, Sir Richard Burton wrote in 1870 that a train he rode in Paraguay was pulled by an "asthmatic little engine." He said it had served on the Balaclava line and was later sent to Paraguay after being considered useless in Buenos Aires.

|

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |