HMS Aboukir (1900) facts for kids

Aboukir, port side, at Malta

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Aboukir |

| Namesake | Battle of Aboukir Bay |

| Builder | Fairfield Shipbuilding, Govan, Scotland |

| Laid down | 9 November 1898 |

| Launched | 16 May 1900 |

| Completed | 3 April 1902 |

| Fate | Sunk by U-9, 22 September 1914 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Cressy-class armoured cruiser |

| Displacement | 12,000 long tons (12,000 t) (normal) |

| Length | 472 ft (143.9 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 69 ft 6 in (21.2 m) |

| Draught | 26 ft 9 in (8.2 m) (maximum) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Complement | 725–760 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

HMS Aboukir was a large warship called an armoured cruiser. She was built for the Royal Navy around 1900. After she was finished, Aboukir joined the Mediterranean Fleet. She spent most of her time there.

In 1912, Aboukir returned home and was put into reserve. This meant she was kept ready but not actively used. When World War I started in August 1914, she was called back into service. She took part in a small way in the Battle of Heligoland Bight. This battle happened just a few weeks after the war began.

Sadly, Aboukir was sunk by a German submarine called U-9. This happened on 22 September 1914. Two of her sister ships were also sunk that day. A total of 527 men from Aboukir's crew died.

Contents

Building and Features of the Ship

Aboukir was designed to weigh about 12,000 long tons (12,000 t). The ship was 472 feet (143.9 m) long from end to end. She was also 69 feet 9 inches (21.3 m) wide. Her deepest part, called the draught, was 26 feet 9 inches (8.2 m).

The ship had two powerful engines. These were 4-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. They produced a total of 21,000 indicated horsepower (16,000 kW) power. This allowed the ship to reach a top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). Thirty large Belleville boilers provided the steam for the engines. Aboukir could carry up to 1,600 long tons (1,600 t) of coal. Her crew had between 725 and 760 officers and sailors.

Ship's Weapons

Aboukir's main weapons were two large 9.2-inch guns. These were placed in single gun turrets. One was at the front and one at the back of the ship. These guns could fire 380-pound (170 kg) shells. They could hit targets up to 15,500 yards (14,200 m) away.

She also had twelve 6-inch guns. These were placed in special rooms called casemates along the sides of the ship. Eight of these guns were on the main deck. They could only be used when the sea was calm. These guns fired 100-pound (45 kg) shells. Their maximum range was about 12,200 yards (11,200 m).

For defense against smaller ships, Aboukir had twelve quick-firing 12-pounder guns. Eight were on the upper deck and four in the ship's main structure. She also carried three 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns. Finally, she had two 18-inch torpedo tubes hidden underwater.

Ship's Protection

The ship had strong armor along its sides at the waterline. This armor was between 2 to 6 inches (51 to 152 mm) thick. It was closed off by 5-inch (127 mm) thick walls called bulkheads. The armor on the gun turrets was 6 inches thick. The casemate armor was 5 inches thick. The protective deck armor was 1–3 inches (25–76 mm) thick. The Conning tower was protected by 12 inches (305 mm) of armor.

Life and Service of HMS Aboukir

Aboukir was started by Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering in Govan, Scotland. This was on 9 November 1898. She was launched into the water on 16 May 1900. In March 1901, she arrived at Portsmouth Dockyard to be finished. She was ready early the next year.

The ship officially joined the navy on 3 April 1902. Her first captain was Charles John Graves-Sawle. Aboukir was sent to the Mediterranean Fleet. She left Portsmouth in early May and arrived in Malta later that month.

She spent two long periods in the Mediterranean. The first was from 1902 to 1905. The second was from 1907 to 1912. In September 1902, she visited Greece. There, she took part in training exercises with other ships. She also helped escort the damaged battleship HMS Hood from Malta to Gibraltar.

When she came home in 1912, she was put into reserve. But when World War I began in August 1914, she was quickly brought back into action. She joined the 7th Cruiser Squadron. This squadron was ordered to patrol an area of the North Sea called the Broad Fourteens. Their job was to support smaller ships protecting the English Channel. This channel was a vital supply route between England and France.

During the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28 August, Aboukir was part of a reserve group. She was off the Dutch coast and did not take part in the fighting.

The Sinking of Aboukir

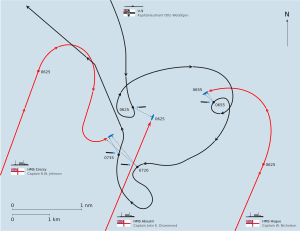

On the morning of 22 September 1914, Aboukir was on patrol. She was with her two sister ships, Cressy and Hogue. They did not have any smaller ships, like destroyers, with them. These smaller ships had gone to find shelter from bad weather.

The three large cruisers were sailing in a line, about 2,000 yards (1,800 m) apart. They were moving at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). The ships were not expecting a submarine attack. However, they had lookouts watching and one gun ready on each side. The weather had improved earlier that morning.

The German submarine U-9, led by Otto Weddigen, was in the area. It had been ordered to attack British transport ships. But the storm had forced it to dive and wait. When it surfaced, it saw the British ships and prepared to attack.

At 6:20 AM, U-9 fired a torpedo at Aboukir. It hit the ship on its left side. Captain John Drummond of Aboukir thought they had hit a mine. He ordered the other two ships to come closer. He wanted to move his wounded men to them.

Aboukir quickly began to tilt to one side. Even though the crew tried to balance the ship, it capsized (turned over) around 6:55 AM. By the time Captain Drummond ordered "abandon ship," only one lifeboat was ready. The others were either broken or could not be lowered.

As Hogue came closer to her sinking sister ship, her captain, Wilmot Nicholson, realized it was a submarine attack. He signaled Cressy to look for a periscope. But Hogue kept getting closer to Aboukir. Her crew threw anything that would float into the water to help the survivors.

Hogue stopped and lowered all her boats. Then, around 6:55 AM, she was hit by two torpedoes. The sudden loss of weight from the torpedoes made U-9 briefly pop to the surface. Hogue's gunners fired at the submarine, but it quickly submerged again. Hogue capsized about ten minutes after being hit. All her watertight doors had been open, so she sank at 7:15 AM.

Cressy tried to ram the submarine, but missed. She then went back to rescuing survivors. But at 7:20 AM, she was also hit by a torpedo. Cressy tilted heavily and then capsized. She sank at 7:55 AM.

Several Dutch ships began rescuing survivors at 8:30 AM. British fishing boats also joined in. More British ships arrived later to help. From all three ships, 837 men were saved. However, 62 officers and 1,397 sailors were lost. Of these, Aboukir alone lost 527 men.

In 1954, the British government sold the rights to salvage (recover) the three ships. A German company bought them. Later, a Dutch company bought them again. This company started recovering metal from the shipwrecks in 2011.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: HMS Aboukir (1900) para niños

In Spanish: HMS Aboukir (1900) para niños