Halifax Explosion facts for kids

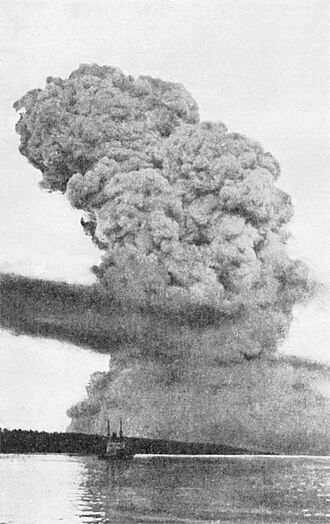

The pyrocumulus cloud produced by the explosion

|

|

| Date | 6 December 1917 |

|---|---|

| Time | 9:04:35 am |

| Location | Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Non-fatal injuries | 9,000 (approximate) |

On the morning of December 6, 1917, a terrible accident happened in the harbour of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. A French cargo ship named Mont-Blanc collided with a Norwegian vessel called Imo. The Mont-Blanc was carrying a huge amount of explosives. After the collision, it caught fire and then exploded.

This massive explosion destroyed a large part of Halifax, especially the Richmond area. Over 1,782 people died from the blast, falling debris, fires, or collapsing buildings. About 9,000 others were injured. At the time, this was the biggest human-made explosion ever. It released a huge amount of energy, like a small nuclear bomb.

The Mont-Blanc was on its way from New York City to France, carrying its dangerous cargo. Around 8:45 AM, it slowly bumped into the Imo. The Imo was empty and heading to New York to pick up supplies for Belgium. The collision caused barrels of a fuel called benzol on the Mont-Blanc's deck to break open. The leaking fuel vapours caught fire from sparks, and the fire quickly grew out of control. About 20 minutes later, at 9:04:35 AM, the Mont-Blanc exploded.

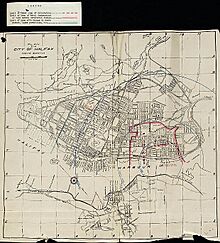

Almost all buildings within 800 metres (half a mile) of the explosion were completely destroyed. This included the entire community of Richmond. The powerful pressure wave from the blast snapped trees, bent metal rails, and flattened buildings. It even pushed the Imo onto the shore. Across the harbour in Dartmouth, there was also a lot of damage. A giant tsunami created by the explosion washed away a Mi'kmaq community that had lived in the Tufts Cove area for many years.

Help started arriving right away, but hospitals quickly became full. Rescue trains came from across Nova Scotia and New Brunswick on the same day. Other trains from central Canada and the Northeastern United States were slowed down by heavy snowstorms. Soon after the disaster, people began building temporary homes for those who had lost everything. An early investigation blamed the Mont-Blanc, but later, it was decided that both ships were partly at fault. Today, there are several memorials in the North End of Halifax to remember the victims.

Contents

Halifax During World War I

Halifax Harbour was a very important place during World War I. It was a main meeting point for groups of merchant ships, called convoys, that were sailing to Britain and France. These convoys carried soldiers, animals, and supplies needed for the war in Europe.

Halifax and Dartmouth grew a lot during wartime. The harbour was a key base for the British Royal Navy in North America. It was also a busy centre for trade. In 1915, the Royal Canadian Navy took over managing the harbour. By 1917, many naval ships, like patrol ships and minesweepers, were based there.

The population of Halifax and Dartmouth grew to about 60,000 to 65,000 people by 1917. German submarines, called U-boats, were attacking ships in the Atlantic Ocean. To protect the ships, the Allies started using a convoy system. Merchant ships would gather safely in Bedford Basin, a protected area of the harbour. From there, they would leave together, guarded by British cruisers and destroyers. This made Halifax a very busy and important port.

The Collision and Fire

The Norwegian ship Imo was leaving Halifax on December 6, 1917. It was heading to New York to pick up relief supplies for Belgium. Its departure had been delayed, so the ship was trying to make up for lost time.

The French cargo ship Mont-Blanc was arriving in Halifax. It was packed with dangerous explosives like TNT, picric acid, and highly flammable benzol fuel. It was supposed to join a convoy in Bedford Basin, but it arrived too late to enter the harbour before the protective nets were raised for the night. Before the war, ships with such dangerous cargo were not allowed in the harbour. However, the threat of German submarines had made the rules less strict.

Ships moving through the narrow part of the harbour, called the Narrows, were supposed to stay on their "right" side. They also had a speed limit of about 5 knots (9 km/h).

How the Ships Collided

The Imo left Bedford Basin around 7:30 AM. It was moving faster than the harbour's speed limit. It met another ship, the SS Clara, which was on the wrong side of the harbour. The pilots agreed to pass each other on their "right" sides. Soon after, the Imo had to move even closer to the Dartmouth shore to avoid a tugboat.

Francis Mackey, an experienced pilot, was guiding the Mont-Blanc. He had asked for special protection because of the ship's dangerous cargo, but none was provided. The Mont-Blanc entered the harbour around 7:30 AM. Mackey saw the Imo approaching and realized it seemed to be heading towards his ship's side. He blew his whistle to show he had the right of way, but the Imo responded with two blasts, meaning it would not change course.

Mackey ordered the Mont-Blanc's engines to stop and turned slightly towards the Dartmouth side. He blew his whistle again, but the Imo again responded with two blasts. Sailors on other ships realized a collision was about to happen. Both ships had cut their engines, but they were still moving slowly towards each other.

In a last effort to avoid a crash, Mackey ordered the Mont-Blanc to turn sharply. But the Imo suddenly reversed its engines. This caused the Imo's front end to swing into the Mont-Blanc. The Imos bow crashed into the Mont-Blancs side.

The Fire and Explosion

The collision happened at 8:45 AM. The damage to the Mont-Blanc was not severe at first. However, barrels of benzol fuel on the deck broke open, spilling fuel everywhere. As the Imo pulled away, sparks were created inside the Mont-Blanc's hull. These sparks ignited the benzol vapours, and a fire quickly started.

The fire spread rapidly up the side of the ship. Fearing an immediate explosion, the captain ordered the crew to abandon ship. They quickly got into two lifeboats and rowed towards the Dartmouth shore. They tried to warn other ships that their vessel was about to explode, but the noise and confusion made it impossible to hear them. The burning Mont-Blanc drifted and eventually ran aground near Pier 6.

A tugboat, Stella Maris, tried to put out the fire, but it was too intense. Other naval rescue boats also approached. Just as they were trying to secure a rope to pull the burning ship away from the pier, the explosion happened.

The Massive Blast

At 9:04:35 AM, the uncontrolled fire on the Mont-Blanc set off its cargo of high explosives. The ship was completely blown apart. A powerful blast wave shot out from the explosion at over 1,000 metres per second. The centre of the explosion reached temperatures of 5,000°C and incredibly high pressures. White-hot pieces of iron rained down on Halifax and Dartmouth.

A huge cloud of white smoke rose to at least 3,600 metres (12,000 feet) into the sky. People felt the blast as far away as Cape Breton Island (207 km away) and Prince Edward Island (180 km away). An area of over 1.6 square kilometres (400 acres) was completely destroyed. The force of the explosion even pushed water out of the harbour, briefly exposing the harbour floor.

A giant tsunami formed as water rushed back in. It rose as high as 18 metres (60 feet) on the Halifax side of the harbour. The tsunami carried the Imo onto the shore in Dartmouth. Many people on nearby rescue boats were killed. Almost all of the Mont-Blanc's crew members survived because they had abandoned ship just in time.

More than 1,600 people died instantly, and another 9,000 were injured. Over 12,000 buildings were destroyed or badly damaged. Hundreds of people watching the fire from their homes were blinded when windows shattered in front of them. Fires started all over Halifax, especially in the North End, where entire city blocks burned.

A brave railway dispatcher named Patrick Vincent (Vince) Coleman saved many lives. He was working near Pier 6 when he learned about the dangerous cargo on the burning Mont-Blanc. He knew a passenger train was coming. Instead of fleeing, he went back to his post and sent urgent telegraph messages to stop the train. His message, "Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys," stopped all incoming trains. Passenger Train No. 10, carrying about 300 people, stopped safely away from the blast. Sadly, Vince Coleman was killed at his post.

Helping Those Affected

Right after the explosion, neighbours and co-workers started digging people out of the rubble. Soon, surviving police officers, firefighters, and military personnel joined in. Anyone with a working vehicle helped transport the wounded to hospitals, which quickly became overwhelmed. The new military hospital, Camp Hill, treated about 1,400 victims on December 6.

Firefighters were among the first to respond. They rushed towards the Mont-Blanc to try and put out the fire before it exploded. After the blast, fire companies came from all over Halifax and even from towns like Amherst, Nova Scotia and Moncton, New Brunswick. Nine Halifax firefighters died trying to help that day.

Royal Navy ships in the harbour sent rescue teams and medical staff ashore. They also took wounded people aboard their ships. A US Coast Guard cutter also sent a rescue party. American navy ships, like the USS Tacoma, changed course to help after feeling the blast and seeing the smoke. They arrived to assist with rescue efforts. An American steamship, Old Colony, was quickly turned into a hospital ship.

At first, many survivors feared the explosion was an attack by German planes. Troops prepared for battle, but within an hour, they switched to rescue roles once they understood what had happened. All available soldiers were called to the North End to help survivors and take them to hospitals.

There was also a scare about a possible second explosion. A cloud of steam from a military ammunition building led to rumours that another blast was coming. Many families fled their homes, which slowed down rescue efforts for a few hours. However, many rescuers ignored the evacuation orders and kept working.

Railway workers also helped, pulling people from the harbour and from under debris. A train from Saint John, which was only slightly damaged by the blast, continued into the city. Passengers and soldiers on board used tools and sheets to help dig people out and bandage their wounds. This train then evacuated the wounded to Truro.

Leading citizens formed the Halifax Relief Commission to organize help. This group managed medical aid, transportation, food, and shelter. They also covered medical and funeral costs. The commission continued its work until 1976, helping with rebuilding and providing support to survivors.

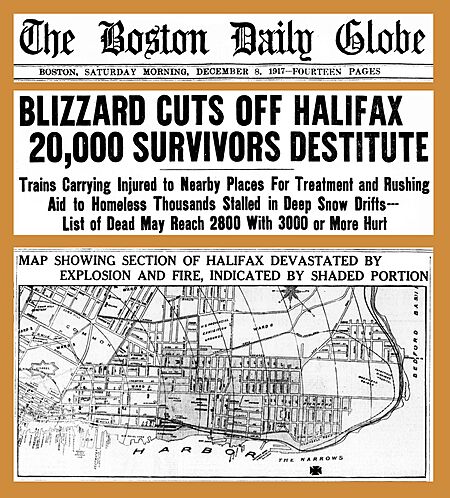

Rescue trains arrived from across Atlantic Canada and the northeastern United States. The first train from Truro arrived by noon, carrying medical staff and supplies. It returned to Truro with the wounded and homeless by 3 PM. The next day, a severe blizzard hit Halifax, bringing 16 inches (41 cm) of snow. This storm made rescue efforts harder, stalling trains and knocking down telegraph lines. However, the snow also helped put out many fires throughout the city.

Damage and Lives Lost

The exact number of people killed is not fully known. The Halifax Explosion Remembrance Book lists 1,782 victims. About 1,600 people died immediately. The last body was found in the summer of 1919. An additional 9,000 people were injured.

The explosion destroyed or damaged 1,630 homes, and another 12,000 were damaged. About 6,000 people lost their homes, and 25,000 had unsafe shelter. Many factories were destroyed, and many workers were among the casualties.

Many people suffered severe eye injuries from flying glass or the bright flash of the explosion. Thousands had been watching the fire from their windows, putting them directly in the path of shattered glass. Doctors performed many eye surgeries, and some people lost both eyes.

The damage cost about CA$35 million in 1917 (which would be much more today). About $30 million in aid was raised, including money from the Canadian government, the British government, and the state of Massachusetts in the US.

Impact on Dartmouth and Communities

Dartmouth was not as crowded as Halifax, but it still suffered heavy damage. Almost 100 people died on the Dartmouth side. Many buildings were damaged or destroyed, and the Nova Scotia Hospital treated many victims.

The Mi'kmaq community of Turtle Grove, located in Tufts Cove on the Dartmouth shore, was very close to the explosion. Their homes were completely destroyed by the blast and tsunami. The exact number of Mi'kmaq who died is unknown. The Turtle Grove settlement was not rebuilt.

The Black community of Africville, on the southern shores of Bedford Basin, was partly protected by hills. However, their homes were still heavily damaged. Five residents died. Africville received little of the donated relief funds and was not included in the city's major rebuilding plans.

Finding Out What Happened

Many people in Halifax first thought the explosion was an attack by Germany. An investigation, called the Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry, was set up to find out what caused the collision.

The inquiry's report in February 1918 blamed the Mont-Blanc's captain, Aimé Le Médec, and its pilot, Francis Mackey. It also blamed Commander F. Evan Wyatt, who was in charge of the harbour. However, a judge later found no evidence to support these charges, and they were dropped.

Later, the owners of the two ships went to court to seek damages from each other. After several appeals, the highest courts decided that both the Mont-Blanc and the Imo were equally to blame for mistakes that led to the collision. No one was ever found guilty of a crime related to the disaster.

Rebuilding Halifax

Soon after the explosion, efforts began to clear debris, fix buildings, and create temporary homes. By January 1918, about 5,000 people still needed shelter. A reconstruction committee built 832 new homes, which were furnished with aid money.

Train service slowly returned, and the North Street Station reopened. Railway yards and piers were cleared and rebuilt. Most piers were working again by late December.

The Richmond neighbourhood in Halifax's North End was hit hardest. Before the explosion, it was a working-class area. After the disaster, the Halifax Relief Commission saw a chance to modernize it. They hired experts to design a new housing plan for Richmond.

The new plan created 326 large homes, built with a new fireproof material called Hydrostone blocks. These homes faced tree-lined, paved streets. The first of these homes were ready by March 1919. The Hydrostone neighbourhood became a new, strong community with homes, businesses, and parks. Today, it is a popular area. However, Africville, another poor area, was not included in these rebuilding efforts.

The Halifax dockyard and its ships, like HMCS Niobe, also needed rebuilding. Despite the damage, a convoy left the harbour on December 11, and dockyard operations resumed before Christmas.

Lasting Impact

The Halifax Explosion was one of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions in history. For many years, it was the standard for measuring other big blasts. For example, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Time magazine said its power was seven times that of the Halifax Explosion.

The many eye injuries from the disaster led to a better understanding of how to treat damaged eyes. Halifax became known as a centre for eye care. The lack of special care for children in such a disaster also inspired a surgeon from Boston, William Ladd, to become a pioneer in pediatric surgery (surgery for children) in North America. The explosion also led to improvements in public health and care for mothers.

For a long time, people in Halifax did not talk much about the explosion because it was so traumatic. The city stopped holding official ceremonies for decades. The second official commemoration was not until the 50th anniversary in 1967.

Today, there are several memorials. The Halifax Explosion Memorial Bells were built in 1985 on Fort Needham Hill, overlooking the explosion site. An annual ceremony is held there every December 6. There are also monuments made from pieces of the Mont-Blanc and memorials for the firefighters who died. Mass graves for victims are marked in cemeteries. The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic has a large exhibit about the Halifax Explosion.

The help that Boston, USA, sent to Halifax after the explosion created a special bond between the two cities. In 1918, Halifax sent a Christmas tree to Boston as a thank you. This tradition was revived in 1971 and continues every year. Nova Scotia now sends a large tree to Boston, which becomes Boston's official Christmas tree, celebrating the goodwill and friendship between the two places.

See also

In Spanish: Explosión de Halifax para niños

In Spanish: Explosión de Halifax para niños