Hawaiian honeycreeper conservation facts for kids

Hawaiian honeycreepers are a special group of birds that live only in Hawai'i. They are part of the finch family. Long ago, there were at least 51 different kinds of honeycreepers, and they were found all over Hawaii's forests. Sadly, today less than half of these amazing birds are still alive. Many things threaten them, like losing their homes, diseases carried by mosquitoes, and new animals that hunt them or compete for their food.

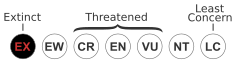

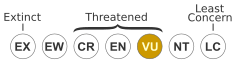

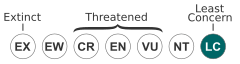

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Extinct species | Critically endangered species | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Endangered species | Vulnerable species | |

|

|

|

| Near-threatened species | Species of least concern | |

Contents

Why Hawaiian Honeycreepers Are in Danger

Hawaiian honeycreepers face many dangers. These include new animals that hunt them, competition for food, loss of their homes, and diseases. One big problem is a disease called avian malaria, which is spread by mosquitoes.

Diseases from Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes carry avian malaria, a sickness that is very bad for honeycreepers. Female mosquitoes spread the disease when they bite an infected bird and then bite a healthy one. The main type of mosquito that carries this disease (Culex quinquefasciatus) arrived in Hawaii over a hundred years before the disease itself. The disease was often carried by birds like the blue-breasted quail. Later, two more mosquito types, the Asian tiger mosquito and the bromeliad mosquito, also came to the islands.

Honeycreepers had not been exposed to avian malaria for millions of years. This means their bodies had not learned how to fight off the disease. Birds on the mainland, however, had slowly developed ways to resist it.

In the 1970s, scientists noticed that native birds were no longer living in lower forests. They had moved to higher places. This was because malaria-carrying mosquitoes could not live in the cold temperatures above about 1,500 meters (4,900 feet). So, many honeycreeper species had to live at higher altitudes, between 1,500 to 1,900 meters (4,900 to 6,200 feet). Global warming is a worry because it might make these higher areas warmer. This could allow mosquitoes to spread even higher, leaving the honeycreepers with no safe place to live.

Losing Their Homes

Another major reason for the honeycreepers' decline is the loss of their natural homes. When people settled in Hawaii, they cut down many forests. They did this to make space for farms, ranches, and other buildings. Even where forests still stand, animals like pigs and goats that were brought to the islands cause a lot of damage. They eat plants and disturb the forest floor. Other harmful animals include cats, which hunt birds. Hawaiian honeycreepers are especially easy targets because they are not used to predators.

Helping the Honeycreepers

Many people are working hard to save the remaining honeycreeper species. Here are some of the ways they are trying to help:

Removing Mosquitoes

One way to help is to get rid of the mosquitoes that spread malaria. This can be done by reducing places where mosquitoes breed. Scientists are also looking into using special chemicals or natural ways to control them. Another idea is to release genetically changed male mosquitoes into the wild. These males cannot have babies, so over time, the mosquito population would shrink.

Breeding Birds in Safety

For some honeycreeper species that are in extreme danger, protecting their natural homes is not happening fast enough. Groups like the Zoological Society of San Diego and The Peregrine Fund have started programs to breed these birds in safe places. The goal is to raise them in captivity and then release them back into the wild. In 2000, a big challenge was not breeding the birds, but finding safe places to release them. This means that managing and restoring their natural homes is very important before these programs can truly succeed.

Clearing Homes of Harmful Animals

Hawaiian honeycreepers are often "specialists." This means they have specific diets and live in particular types of habitats. This makes them very sensitive to "generalist" animals that have been brought to the islands. Generalists can eat many different things and live in various places. Other birds that were brought to Hawaii compete with honeycreepers for food and also carry diseases like avian malaria. However, it is hard to remove these introduced birds because they are difficult to catch and can fly far.

Introduced animals like pigs and goats also cause damage. Removing these larger animals often means building fences and directly taking them out of the area. In places where pigs have been removed, the plants in the forest have started to grow back. However, honeycreeper numbers are still going down. This might be because of other introduced predators like feral cats, small Asian mongooses, and three types of rat.

A Glimmer of Hope: The ʻAmakihi

The common ʻamakihi (Hemignathus virens) is one of the honeycreeper species still found on Hawai’i Island. It is a small bird that can eat many different things. In the past, many ʻamakihi birds died from avian malaria. But surprisingly, some have been found living in lower areas, below 400 meters (1,300 feet), even though they are exposed to the disease there. About 90% of these birds showed that they had caught the disease but survived it. This suggests that the ʻamakihi might be slowly developing a way to resist malaria. However, this might only be happening in certain areas.

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |