Laysan honeycreeper facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Laysan honeycreeper |

|

|---|---|

|

|

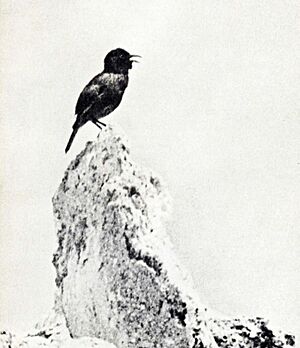

| Male Laysan honeycreeper photographed by Donald R. Dickey in 1923, a few days before the extinction of the species | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Carduelinae |

| Genus: | Himatione |

| Species: |

†H. fraithii

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Himatione fraithii Rothschild, 1892

|

|

|

|

| Map of the Hawaiian Islands showing Laysan Island in the lower left inset box | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

H. fraithi

Rothschild, 1892 H. freethii Rothschild, 1893–1900 H. freethi Rothschild, 1893–1900 H. frethii Schauinsland, 1899 H. sanguinea fraithii Hartert, 1919 H. sanguinea fraithi Delacour H. sanguinea freethii Amadon, 1950 H. sanguinea freethi Pratt et al., 1987 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Laysan honeycreeper (Himatione fraithii), also known as the Laysan ʻapapane, was an extinct bird. It was a type of finch that only lived on Laysan Island in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. People first saw this bird in 1828. It got its scientific name from Walter Rothschild in 1892. The bird was placed in the same group (genus Himatione) as the ʻapapane. The name fraithii was meant to honor George D. Freeth, who was in charge of Laysan, but his name was spelled wrong.

For many years, people thought the Laysan honeycreeper was just a type of ʻapapane. But after more research in the 21st century, scientists decided it was its own unique species again. Like other Hawaiian honeycreepers, its ancestors likely came from Asia.

The Laysan honeycreeper was about 13 to 15 cm (5 to 6 in) long. It was a bright scarlet red, with a hint of golden orange on its head and chest. Its wings, tail, beak, and legs were dark brown. Young birds were brown with lighter undersides. Its beak was thin and curved downwards. Males and females looked similar, but females had slightly shorter beaks, wings, and tails. The related ʻapapane is blood-red all over and has a longer beak. The Laysan honeycreeper's song was described as soft and sweet.

Laysan is a small, remote coral island about 3.6 square kilometers (1.4 sq mi) in size. The honeycreeper lived all over the island. It was most common in the middle of the island, where there was tall grass and small bushes near a lagoon.

This bird was very active. It would sometimes fly into buildings to hunt moths or to rest at night. It ate both nectar from flowers and insects. Unlike the ʻapapane, it also looked for food on the ground. It would eat caterpillars and moths, but only the soft parts of the moths. The Laysan honeycreeper built its nest from fine grass and roots. It probably laid eggs between January and June, usually four or five at a time. The eggs were dull white with spots.

The Laysan honeycreeper was not very common when it was first discovered. In 1903, domestic rabbits were brought to the island. These rabbits destroyed almost all the plants. By 1923, Laysan Island was mostly barren and desert-like. During a scientific trip called the Tanager Expedition, only three Laysan honeycreepers were found. One of them was even filmed. A few days later, on April 23, a big sandstorm hit the island. The last birds died because there was no longer any plant cover to protect them. The loss of plants on Laysan led to the extinction of three out of five unique land birds on the island.

Contents

Discovering the Laysan Honeycreeper

The Laysan honeycreeper was first seen on Laysan Island on April 3, 1828. This was reported by C. Isenbeck, a surgeon on a Russian ship. His report was published in 1834 by the German naturalist Heinrich von Kittlitz. Isenbeck mentioned a "red bird" and a "humming bird", likely both referring to the honeycreeper. He probably called it a "humming bird" because it drank nectar.

In 1892, the British zoologist Walter Rothschild officially described and named seven new bird species from Hawaii. These birds were collected by Henry C. Palmer and George C. Munro in 1891. Rothschild named the honeycreeper Himatione fraithii. He put it in the finch family, specifically the Hawaiian honeycreeper group. He noticed it looked similar to the ʻapapane (H. sanguinea), which lives on the main Hawaiian islands. The name Himatione comes from a Greek word for a crimson cape, referring to the ʻapapane's red color.

The specific name fraithii was meant to honor George D. Freeth. He was the self-appointed US governor of Laysan and helped the collectors. However, his name was misspelled. Rothschild later tried to correct the spelling to freethi, but he also used other spellings.

For most of the 20th century, many scientists thought the Laysan honeycreeper was just a subspecies of the ʻapapane. However, in 2011, Peter Pyle, an American ornithologist, pointed out that the original spelling fraithii should be used. This is because, by scientific rules, the first name given is usually the correct one, even if it was a mistake.

In 2015, scientists formally suggested that the Laysan honeycreeper should be considered its own full species again, and its name changed back to fraithii. They also suggested calling it "Laysan honeycreeper" instead of "Laysan ʻapapane". They felt it was important for at least one Hawaiian honeycreeper to keep the word "honeycreeper" in its name. These changes were accepted by major bird organizations that same year.

Today, there are at least 105 known specimens of the Laysan honeycreeper in museums around the world. These include 24 in the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum in Honolulu and 20 in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. There are also at least two skeletons, three nests, and one egg preserved.

How the Laysan Honeycreeper Evolved

Scientists believe the Laysan honeycreeper evolved from the ʻapapane. The ʻapapane likely flew to Laysan Island and then changed over time to become a new species. In 1899, a German zoologist named Schauinsland saw the Laysan honeycreeper as an example of how new species can form when they are isolated on an island.

Some scientists thought that the Laysan honeycreeper and the Laysan finch spent more time on the ground than their relatives. They also noticed their wings were a bit short, which might have been a sign of them adapting to island life.

In 1995, scientists suggested that the Laysan honeycreeper's skull showed it was a distinct species. They thought it might be a very old type of honeycreeper, rather than one that had changed a lot for Laysan's environment. They also believed that Hawaiian honeycreepers didn't just live in mountains, but were wiped out from lower areas by humans long ago.

A study in 2004 looked at the bones of different honeycreepers. It showed that the Laysan honeycreeper was closely related to the ʻapapane.

Scientists have long known that Hawaiian honeycreepers are a unique group of finches. They have many different beak shapes and feather patterns because they adapted to different island environments. Genetic studies in the 21st century showed that Hawaiian honeycreepers are closely related to a group of finches from Asia. This means their ancestors likely came from Asia. The different Hawaiian islands formed at different times, and the birds changed as new islands appeared.

What the Laysan Honeycreeper Looked Like

The Laysan honeycreeper was a small bird, about 13 to 15 cm (5 to 6 in) long. Its wing was about 6.4 to 6.9 cm (2.5 to 2.7 in) long, and its tail was about 6.1 cm (2.4 in) long. Its beak was about 1.4 cm (0.55 in) long.

It was bright scarlet red, with a slight golden orange color on its head, chest, and upper belly. The rest of its upper body was orange-scarlet. Its lower belly was dusky gray, fading to brownish-white. The feathers under its tail were grayish. Its wings, tail, beak, and legs were dark brown. Its eyes were black with a brown outline. Young birds were brown, with lighter undersides and green edges on their wing feathers. The beak was thin and curved downwards.

Males and females looked alike, but the female's beak, wings, and tail were a bit shorter. One scientist noted that the pictures of the Laysan honeycreeper made it look too pale. Birds that had just shed their old feathers were a deeper red and looked more like the ʻapapane.

The ʻapapane is different because it is blood-red all over, with black wings and tail. It also has whiter feathers under its tail and a longer beak. Some scientists thought the Laysan honeycreeper's feathers might have faded due to the strong sunlight on the island. However, others pointed out that some feathers, like the white ones under the tail, cannot fade because they don't have color to begin with.

The song of the Laysan honeycreeper was described as soft and "sweet," with several notes. It was usually quiet, except during the breeding season in January and February, when it would sing a lot. One collector even said a honeycreeper sang in his hand after he caught it, and it seemed unafraid.

Where the Laysan Honeycreeper Lived

The Laysan honeycreeper only lived on Laysan Island. This remote island is about 3.6 square kilometers (1.4 sq mi) in size. It's the largest of the northwestern Hawaiian Islands in the central Pacific Ocean. Laysan is what's left of an old, tall island formed by volcanoes. It has low hills up to 12 meters (40 ft) high.

The island has a lagoon in the middle, which takes up about one-fifth of its area. The island is surrounded by sand dunes and used to have many different kinds of plants. However, by 1923, much of the plant life was destroyed by human activities, making the island look like a desert. Luckily, the plants had mostly grown back by 1973.

In 1903, a scientist noted that the Laysan honeycreeper could be found all over the island. But it was most common in the middle, among tall grass and small bushes near the lagoon. This was also a favorite spot for nesting. The birds also liked to visit grass tops and other plants near the lagoon's edges. Their bright red feathers made them easy to spot among the green bushes. This bird was the only finch in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands that ate nectar.

Behavior and Diet

Not many scientists saw the Laysan honeycreeper, so we don't know a lot about its daily life. It was very active and often seen near buildings. While not as tame as some other birds, it would sometimes go inside buildings to hunt moths or to sleep at night. They were usually seen in pairs.

Its flight was described as "weak and low." It could even be caught with a hand net. They would gather around houses and drink rainwater from leaks, which suggested they needed more water than other birds on the island.

The Laysan honeycreeper ate both nectar and insects. Insects were probably a more important part of their diet during some seasons. Unlike the ʻapapane, it also looked for food on the ground. The bird originally drank nectar from a native flower called maiapilo. When that flower disappeared, it switched to other plants like [[ʻākulikuli]] and [[ʻihi]]. It also visited nohu and pōhuehue flowers.

The Laysan honeycreeper spent its day looking for food. It would walk around like pipits (another type of bird) to find small insects. It also drank from flowers with its brush-like tongue. It would quickly move from flower to flower, putting its beak precisely between the petals. This reminded some scientists of hummingbirds, but the honeycreeper walked instead of hovering. It ate small green caterpillars and large brownish moths called millers. These moths were common on the island. The honeycreepers would pull moths from cracks, hold them with one foot, and eat the soft parts, leaving the wings behind.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

It was hard to find the nests of the Laysan honeycreeper. One nest was found in the middle of a grass tuft, about 60 cm (2 ft) above the ground. It also nested in thick shrubs. The nest was made of fine grass and roots, sometimes described as loosely built. The inside of the nest was about 5.6 cm (2.2 in) across and 4.1 cm (1.6 in) deep. It was lined with fine roots, petrel feathers, and brown down from Laysan albatrosses.

We don't know much about when the Laysan honeycreeper bred. One observer said the bird was singing a lot in January and February, which suggests the breeding season was between then and June. Scientists collected nests with eggs in May. The female usually laid four or five eggs, though some nests had three. The eggs were dull white with grayish spots, especially at the larger end. A typical egg was about 18 by 13.7 mm (0.71 by 0.54 in).

Why the Laysan Honeycreeper Disappeared

The Laysan honeycreeper was never very common. In 1828, it was already considered uncommon. In 1890, it was called the rarest bird on the island. Laysan Island was used for mining guano (bird droppings) starting in 1890. In 1903, the manager of the guano operation, Max Schlemmer, brought domestic rabbits, European hares, and guinea pigs to the island. He wanted to start a meat business and entertain his children. The business failed, but the rabbits quickly destroyed the island's plants.

In 1909, US president Theodore Roosevelt made Laysan and other Hawaiian islets a bird preserve. However, in 1911, scientists found rabbits everywhere. They warned that all the plants would be gone if nothing was done. They also saw thousands of bird skeletons left by feather hunters. They estimated only 300 Laysan honeycreepers were left and believed they would die out if their food supply wasn't saved.

In 1912, scientists noted that the honeycreepers were less common than other birds. Because plants were disappearing, the birds were forced to live in small patches of wild tobacco and grass. In 1915, one report estimated 1000 honeycreepers, but this was likely too high.

In 1923, the Tanager Expedition visited Laysan to get rid of the rabbits. By then, the island was a "barren wasteland of sand." Only three Laysan honeycreepers were found alive. They were looking for small flies among rocks. On April 18, a scientist filmed one male honeycreeper singing on a coral rock. This is probably the last film of this bird.

A few days later, on April 23, a strong sandstorm hit Laysan for three days. The last three Laysan honeycreepers died during this storm. Their deaths were blamed on the lack of plant cover to protect them. The destruction of Laysan's plants led to the extinction of three out of five unique land birds on the island.

The rabbits were removed from Laysan by the Tanager Expedition in 1923. This allowed the plants to grow back, but it was too late for the Laysan honeycreeper. Many searches for the bird were done later, but none were ever found.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |