Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802 facts for kids

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | Act for the preservation of the Health and Morals of Apprentices and others employed in Cotton and other Mills, and Cotton and other Factories. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 42 Geo. 3. c. 73 |

| Introduced by | Sir Robert Peel, 1st Baronet (Commons) |

| Territorial extent | Great Britain and Ireland |

Quick facts for kids Dates |

|

| Royal assent | 22 June 1802 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Factory and Workshop Act 1878 |

|

Status: Repealed

|

|

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, also known as the Factory Act 1802, was an important law passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Its main goal was to make working conditions better for young apprentices in cotton mills.

This law was suggested by Sir Robert Peel. He became worried about the issue after a serious illness spread in one of his own cotton mills in 1784. He later said this was due to "very bad management."

The Act said that cotton mills and factories needed good air flow (ventilation) and had to be kept clean. Young apprentices working there were supposed to get a basic education. They also had to go to a religious service at least once a month. The law also made sure they received clothes. Their working hours were limited to no more than twelve hours a day, not including meal breaks. They were also not allowed to work at night.

However, this law was not properly enforced. It also did not help "free children," who were children working in mills but not as apprentices. These "free children" quickly became a much larger group than the apprentices. It was easier for Parliament to make rules for apprentices. But making rules for how employers treated other workers, including children, was a new and difficult idea.

Because of this, it wasn't until 1819 that another law was passed. This was the Cotton Mills and Factories Act 1819, also pushed by Sir Robert Peel and his son, Robert. This later law tried to limit working hours and set a minimum age for "free children" in cotton mills. Even though the 1819 Act also struggled with enforcement, it helped pave the way for future Factory Acts. These later laws would truly change the industry and create better ways to enforce rules. Still, the 1802 Act was the first law to officially recognize the problems of child labor in cotton mills.

Why the Law Was Needed

During the early Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom, many cotton mills used water power. This meant they were built in places where water was available. Often, there weren't enough workers nearby. So, mill owners brought in workers from other places.

A cheap source of workers was "parish apprentices." These were poor children whose local church or government (parish) was supposed to help them learn a trade. Mill owners would make deals with distant parishes to hire, house, and feed these apprentices. By 1800, about 20,000 apprentices worked in cotton mills.

These young apprentices were often treated badly by some owners. They faced dangers from accidents, poor health from their work, and sickness from working too much. They also caught contagious diseases like smallpox, typhoid, and typhus, which were common then. Mills and factories were often kept warm and without drafts to prevent threads from breaking. This close, enclosed space allowed diseases to spread very quickly.

Around 1780, Robert Peel built a water-powered cotton mill near Radcliffe. This mill used child labour from workhouses in Birmingham and London. These children were not paid and had to work as apprentices until they were 21. They slept on an upper floor of the building and were locked in. Shifts often lasted 10 to 10 and a half hours, not including meal breaks. The apprentices "hot bunked," meaning one child would sleep in a bed just left by another child starting their shift. Peel himself admitted that conditions at his mill were "very bad."

In 1784, magistrates in Salford Hundred learned about a "low, putrid fever" that had been spreading for months in the cotton mills and among the poor in Radcliffe. Doctors from Manchester, led by Dr. Thomas Percival, were asked to find the cause and stop the spread. They couldn't identify the exact cause. Their ideas were based on the belief that fevers spread through bad air. So, they suggested removing bad smells and improving ventilation.

- Windows and doors should be left open every night and during lunch breaks. When the mill was running, as many windows as possible should be open.

- New chimneys should be built in each work room. Fires should be lit to improve air flow and fight sickness with their "strong, penetrating, and pungent" smoke.

- Rooms should be swept daily. Floors should be washed with lime water once a week. Walls and ceilings should also be whitewashed two or three times a year.

- Rooms should be cleaned with smoke (fumigated) weekly using tobacco.

- Toilets should be washed daily and have good air flow so smells didn't reach work rooms.

- Old, bad oil used for machines should be replaced with cleaner oil.

- All employees should help keep the factory clean to prevent sickness. Children should bathe sometimes. Clothes of sick people should be washed and cleaned with smoke before being worn again. People who died of fever should be wrapped quickly in cloth. Those nearby should smoke tobacco to avoid getting sick.

The doctors also worried about the overall well-being of the mill children. They strongly suggested:

- Longer breaks at noon and earlier finishing times in the evening for all mill workers.

- This was especially important for children under 14. They said that playing and being active was necessary for children's bodies to grow strong and healthy.

- They also pointed out that children should not be stopped from learning, as childhood is the only time they can truly improve themselves.

Because of this report, the magistrates decided not to allow parish apprentices to work in cotton mills at night or for more than ten hours a day. Conditions at Peel's Radcliffe mill improved. In 1795, a book called A Description of the Country from thirty to forty miles round Manchester said that the health of Peel's workers was due to his "wise and kind rules" and the healthy air.

Peel's Bill

In 1795, doctors in Manchester, including Dr. Percival, formed the Manchester Board of Health. This group immediately looked into how children were employed in Manchester factories. They heard from people like Peel, who was now a Member of Parliament. The board concluded:

- Children and others in large cotton factories easily caught fevers. Once someone got sick, the illness spread quickly among those working closely together. It also spread to their families and neighborhoods.

- Large factories were generally bad for the health of workers, even without specific diseases. This was because of long hours, bad air, and a lack of active play needed for children and young people to grow strong.

- Working at night and for too many hours during the day harmed children's health and shortened their lives. It also sometimes encouraged parents to be lazy or wasteful, living off their children's hard work.

- Children in factories usually had no chance to get an education or learn about morals or religion.

- Some cotton factories had excellent rules, showing that many of these problems could be fixed. The board felt that a general system of laws was needed to make sure all such workplaces were run wisely and kindly.

Peel, likely one of the factory owners with good rules, introduced his bill in 1802. He said he knew there was "gross mismanagement" in his own factories. He claimed he didn't have time to fix them himself, so he was getting a law passed to do it for him. However, given his work with the Manchester Board of Health, this might have been a polite way of speaking, not the full story.

In 1816, Peel introduced another Factory Bill. He explained to a committee why more laws were needed. He said that his own factory once employed nearly a thousand children. He often saw that they looked unhealthy and were not growing properly. The working hours were set by supervisors who were paid based on how much work was done. This often made them force children to work too many hours. They would stop complaints with small gifts.

Peel said that after seeing the problems in his own factories and learning that similar issues existed elsewhere, he sought help from Dr. Percival and other experts. He then introduced the 1802 Act to regulate parish apprentices. He noted that after the Act, children's health improved, and contagious diseases became rare.

The Act faced little opposition in Parliament. There was some talk about whether it should apply to all factories and all workers. But this idea was rejected. The Act was only meant to ensure education for apprentices, not to improve conditions for all factory workers.

What the Law Said

The rules of the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act came into effect on December 2, 1802. They applied to all mills and factories that employed three or more apprentices. However, if a factory had fewer than twenty total workers, it was exempt.

- Cleanliness and Air: All mills and factories had to be cleaned at least twice a year with quicklime and water. This included ceilings and walls. Buildings also needed enough windows and openings for fresh air.

- Clothing: Each apprentice was to receive two sets of clothes, including proper linen, stockings, hats, and shoes. They were to get a new set every year.

- Working Hours: Working hours were limited to 12 hours a day, not including meal breaks. Apprentices were no longer allowed to work at night (between 9 pm and 6 am). Factories were given time to adjust, but all night work for apprentices had to stop by June 1804.

- Education: All apprentices had to be taught reading, writing, and arithmetic for the first four years of their apprenticeship. This was supposed to happen every working day during normal working hours. The law didn't say how much time should be spent on it. Classes were to be held in a special part of the mill or factory.

- Religion: Every Sunday, for one hour, apprentices were to be taught about the Christian religion. Every other Sunday, a church service was to be held in the factory. Once a month, the apprentices had to visit a church. They were to be prepared for confirmation in the Church of England between the ages of 14 and 18. A clergyman had to check on them at least once a year.

- Sleeping Arrangements: Male and female apprentices had to sleep in separate areas. No more than two apprentices were allowed per bed.

- Inspections: Local magistrates had to choose two inspectors, called "visitors." One had to be a clergyman and the other a Justice of the Peace. Neither could have any connection to the mill or factory. These visitors could fine owners for not following the law. They could also visit at any time of day to inspect the premises.

- Displaying the Act: The law had to be displayed in two places in the factory. Owners who did not follow any part of the Act could be fined between £2 and £5.

How the Law Worked

The Act required magistrates to appoint visitors and gave them power to inspect mills. However, it did not force them to use these powers. So, unless local magistrates were very interested in the issue, the law was not well enforced. When factories were inspected, the visitors were not trained experts. They were not like the paid Factory Inspectorate that was set up by a later law in 1833.

Also, the Act only applied to apprentices. It did not apply to "free children." Their fathers had the right to decide their children's work terms, and the Act did not change this.

New steam engines made steam-powered cotton mills possible. These mills were already running in Manchester by 1795. They used "free children" from the local area. Parish apprentices had been useful because they were tied to the mill, no matter how far away the mill was for water power. But if a mill no longer needed to be far away, having apprentices became a problem. Apprentices had to be housed, clothed, and fed, even if the mill wasn't selling much. They were more expensive than "free children," whose wages could be lowered if the mill worked fewer hours. "Free children" could also be fired if they got sick or injured. Because of this, using "free children" became more common. The 1802 Act became largely useless within its limited scope, and it didn't apply to most factory children.

In 1819, when Peel tried to pass a new law to create an eleven-hour workday for all children under 16 in cotton mills, a committee heard evidence. A magistrate from Bolton had checked 29 local cotton mills. 20 of them had no apprentices but employed 550 children under 14. The other nine mills had 98 apprentices and 350 children under 14. Apprentices were mostly found in larger mills, which often had slightly better conditions. Some even worked 12 hours a day or less. For example, the Grant brothers' mill worked 11.5 hours a day. It was described as having "perfect ventilation; all the apprentices, and in fact all the children, are healthy, happy, clean, and well clothed; proper and daily attention is paid to their instruction; and they regularly attend divine worship on Sundays." But in other mills, children worked up to 15 hours a day in bad conditions. For example, Gortons and Roberts' Elton mill was described as "Most filthy; no ventilation; the apprentices and other children ragged, puny, not half clothed, and seemingly not half fed; no instruction of any sort; no human beings can be more wretched."

Even though the 1802 Act was mostly ineffective, it is seen as the very first health and safety law. It opened the door for future rules about industrial workplaces. For example, its rule that factory walls had to be whitewashed remained a legal requirement until the Factories Act 1961.

People have different ideas about the deeper meaning of the Act. Some scholars believe it marked a shift away from laissez-faire capitalism (where the government doesn't interfere with business). Others see it as the point where the government started to recognize its responsibility for very poor children and their living conditions. It has also been seen as a sign of future laws about public health in towns. However, some see it as one of the last examples of an older law, the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1601, which said that poor children should be taught a trade. During the debates about the bill, this idea was used to argue against making the law apply more widely.

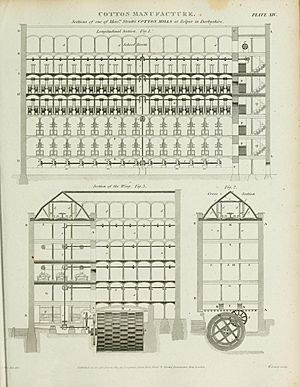

Images for kids

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |