Henrietta Lacks facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henrietta Lacks

|

|

|---|---|

Henrietta Lacks c. 1945–1951

|

|

| Born |

Loretta Pleasant

August 1, 1920 Roanoke, Virginia, U.S.

|

| Died | October 4, 1951 (aged 31) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.

|

| Cause of death | Cervical cancer |

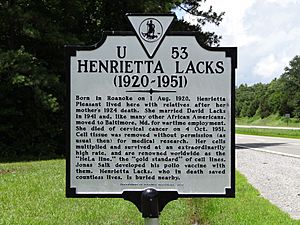

| Monuments | Henrietta Lacks Health and Bioscience High School; historical marker at Clover, Virginia |

| Occupation | Housewife, tobacco farmer |

| Height | approx. 5 ft (150 cm) |

| Spouse(s) | David Lacks (1915–2002) m. 1941 |

| Children | Lawrence Lacks Elsie Lacks (1939–1955) David "Sonny" Lacks Jr. Deborah Lacks Pullum (1949–2009) Zakariyya Bari Abdul Rahman (born Joseph Lacks) |

| Parent(s) | Eliza (1886–1924) and John Randall Pleasant I (1881–1969) |

Henrietta Lacks (born Loretta Pleasant; August 1, 1920 – October 4, 1951) was an African-American woman. Her cancer cells became the source of the HeLa cell line. This was the first "immortalized human cell line" and is very important in medical research. An immortalized cell line means cells can grow and reproduce forever under certain conditions. HeLa cells are still used today for valuable medical data.

Lacks did not know her cells were taken. Doctors took them from a tumor during her cancer treatment. This happened at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1951. A scientist named George Otto Gey then grew these cells. He created the HeLa cell line. At that time, doctors did not need permission to use cells taken during treatment. Henrietta or her family were never paid for these cells.

Researchers knew about HeLa cells' origins after 1970. But the Lacks family did not know until 1975. When the public learned where the cells came from, it raised questions. People wondered about privacy and patients' rights.

Contents

Henrietta Lacks's Life Story

Her Early Years

Henrietta Lacks was born Loretta Pleasant on August 1, 1920. Her parents were Eliza and John Pleasant. She was born in Roanoke, Virginia. People remember her with hazel eyes and red nail polish. Her family is not sure how her name changed to Henrietta. They called her Hennie.

When Henrietta was four, her mother died. Her father could not care for all ten children alone. So, he moved the family to Clover, Virginia. The children went to live with different relatives. Henrietta lived with her grandfather, Thomas Lacks. She lived in an old log cabin that used to be slave quarters. She shared a room with her cousin and future husband, David "Day" Lacks.

Like many in her family, Henrietta worked as a tobacco farmer. She started at a young age. She helped with animals and the garden. She worked in the tobacco fields. She went to a school for black children two miles away. She stopped school in sixth grade to help her family.

In 1935, when she was 14, she had her first son, Lawrence. In 1939, her daughter Elsie was born. Both children were with Day Lacks. Elsie had special needs.

Marriage and Family Life

On April 10, 1941, Henrietta and David "Day" Lacks got married. Later that year, they moved to Turner Station, Maryland. This was near Dundalk, Maryland. Day got a job at Bethlehem Steel. Turner Station was a large African-American community.

In Maryland, Henrietta and Day had three more children. They were David "Sonny" Jr. in 1947, Deborah in 1949, and Joseph in 1950. Henrietta had her last child at Johns Hopkins Hospital. This was just before her cancer diagnosis. Joseph (later called Zakariyya) believes his birth was a miracle. He felt he was "fighting off the cancer cells." Around this time, Elsie was placed in a hospital. She died there in 1955 at age 15.

Both Henrietta and Day Lacks were Catholic.

Her Illness and Treatment

On January 29, 1951, Henrietta Lacks went to Johns Hopkins Hospital. It was the only hospital in the area that treated black patients. Her doctor, Howard W. Jones, took a small tissue sample, called a biopsy. Soon after, Lacks was told she had a serious type of cancer. Doctors later found she had been misdiagnosed. But the treatment would have been the same.

Lacks went home a few days later. She was told to return for X-ray treatments. During her treatments, doctors took two tissue samples. One was healthy tissue, the other was cancerous. They took these samples without her permission. These samples went to George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher. The cells from the cancerous sample became the HeLa "immortal cell line." These cells are still used in biomedical research today.

Her Death and Burial

On August 8, 1951, Henrietta Lacks was 31 years old. She went to Johns Hopkins for treatment. She asked to stay because of severe stomach pain. She received blood transfusions. She stayed at the hospital until she died on October 4, 1951. An examination after her death showed the cancer had spread throughout her body.

Henrietta Lacks was buried in an unmarked grave. It was in her family's cemetery in Lackstown, Virginia. Lackstown was land owned by her family in the past.

Her exact burial spot was unknown for many years. Her family believed it was near her mother's grave. In 2010, Roland Pattillo, a doctor who knew the Lacks family, gave a headstone for Henrietta. This led her family to get a headstone for Elsie Lacks too. Henrietta's headstone has a special message from her grandchildren:

Henrietta Lacks, August 1, 1920 – October 4, 1951

In loving memory of a phenomenal woman,

wife and mother who touched the lives of many.

Here lies Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal

cells will continue to help mankind forever.

Eternal Love and Admiration, From Your Family

HeLa Cells and Medical Research

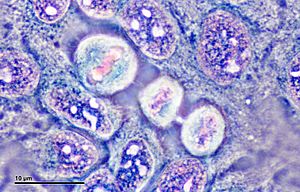

George Otto Gey was the first to study Lacks's cancer cells. He noticed they grew very fast. They also stayed alive much longer than other cells. Before this, lab cells only lived a few days. This was not enough time for many tests. Henrietta's cells were the first that could divide many times without dying. This is why they are called "immortal."

After Lacks died, Gey's assistant took more HeLa samples. Gey started a cell line from Lacks's sample. He isolated one cell and kept dividing it. This meant the same cell could be used for many experiments. They were called HeLa cells. This was because Gey used the first two letters of the patient's first and last names.

HeLa cells can reproduce quickly in a lab. This has led to many important discoveries. For example, in 1954, Jonas Salk used HeLa cells. He used them to develop the polio vaccine. To test his vaccine, the cells were made in large amounts. This was the first cell production factory.

HeLa cells were in high demand. They were sent to scientists worldwide. They were used for research on cancer, AIDS, and the effects of radiation. They also helped with gene mapping and other scientific studies. HeLa cells were the first human cells successfully cloned in 1955. They have been used to test how humans react to tape, glue, and cosmetics. There are almost 11,000 patents that involve HeLa cells.

In the early 1970s, many other cell cultures became accidentally mixed with HeLa cells. Because of this, Henrietta Lacks's family received requests for blood samples. Researchers wanted to learn about the family's genes. This would help them tell HeLa cells apart from other cells.

The family was confused and worried. They wondered why so many people wanted their blood. In 1975, the family learned by chance that Henrietta's cells were still being used. The family had never talked about Henrietta's illness. But now, with all the questions, they started to ask about their mother.

Concerns About Consent and Privacy

Henrietta Lacks and her family did not give permission for her cells to be taken. At that time, permission was not usually asked for. The cells were used for medical research and for making money. In the 1980s, the family's medical records were published. This was also without their permission.

In 1990, a court case called Moore v. Regents of the University of California dealt with a similar issue. The court decided that a person's discarded tissues and cells are not their property. This means they can be used for business.

In March 2013, scientists published the DNA sequence of HeLa cells. The Lacks family found out about this from author Rebecca Skloot. The family was concerned about their genetic information being public. Jeri Lacks Whye, Henrietta's grandchild, told The New York Times her main worry was privacy. She worried about what information about her grandmother, children, and grandchildren would be out there.

In August 2013, the family and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) made an agreement. The family gained some control over who could access the cells' DNA sequence. They also got a promise to be recognized in scientific papers. Two family members also joined a committee. This committee controls access to the sequence data.

In October 2021, Lacks's family filed a lawsuit. They sued Thermo Fisher Scientific. They said the company made money from HeLa cells without Lacks's consent. They asked for all the company's profits from the cells.

Honoring Henrietta Lacks

In 1996, Morehouse School of Medicine started the annual HeLa Women's Health Conference. This conference honors Henrietta Lacks and her cells. It also recognizes the contributions of African Americans to medicine. The mayor of Atlanta declared October 11, 1996, "Henrietta Lacks Day."

Lacks's contributions are celebrated every year in Turner Station. In 1997, Congressman Robert Ehrlich recognized Lacks. He presented a resolution for her contributions to medical science.

In 2010, Johns Hopkins started the Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture Series. This honors Henrietta Lacks and the global impact of HeLa cells.

In 2011, Morgan State University gave Lacks an honorary doctorate. Also in 2011, a new high school in Vancouver, Washington, was named after her. It was called the Henrietta Lacks Health and Bioscience High School.

In 2014, Lacks was added to the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame. In 2017, a minor planet in the main asteroid belt was named "359426 Lacks" in her honor.

In 2018, The New York Times published an obituary for her. This was part of a project to recognize overlooked historical figures. Also in 2018, the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of African-American History and Culture added a portrait of Lacks by Kadir Nelson.

On October 6, 2018, Johns Hopkins University announced plans to name a research building after Lacks. This was announced at the 9th annual Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture. The university president said the building would honor her impact on science. It would also highlight the importance of ethics in research. The building will support programs that involve the community in research.

In 2020, Lacks was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

In 2021, a law called the Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act became law. It requires a study on barriers for underrepresented groups in cancer trials.

In October 2021, the University of Bristol in the UK unveiled a statue of Lacks. It was created by Helen Wilson-Roe. It was the first statue of a black woman made by a black woman for a public space in the United Kingdom.

On October 13, 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) gave an award to Lawrence Lacks. This was in recognition of his mother's contribution to science. The chief scientist at WHO said no other cell line has been used so much.

On March 15, 2022, U.S. Representative Kwesi Mfume proposed a law. It would give Henrietta Lacks the Congressional Gold Medal. This is a very high civilian honor in the United States.

On December 19, 2022, it was announced that a bronze statue of Henrietta Lacks would be put up in Roanoke, Virginia. It will be in Henrietta Lacks Plaza, which was renamed from Lee Plaza.

See also

In Spanish: Henrietta Lacks para niños

In Spanish: Henrietta Lacks para niños

- List of contaminated cell lines

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |