Herjolfsnes facts for kids

|

Ikigait

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Wikidata at line 70: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).

Herjolfsnes peninsula, looking Southeast

|

|

| Location | 50 km Northwest of Cape Farewell, Greenland |

|---|---|

| Region | Greenland |

| Coordinates | 59°59′0″N 44°42′0″W / 59.98333°N 44.70000°W |

| History | |

| Associated with | Norsemen |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1921 |

| Archaeologists | Poul Nörlund |

Herjolfsnes was an important Norse settlement in Greenland. It was located about 50 kilometers northwest of Cape Farewell. A man named Herjolf Bardsson started it in the late 900s. People believe it lasted for about 500 years. We don't know exactly what happened to the people who lived there. Today, Herjolfsnes is famous because archaeologists found amazing, well-preserved clothes from the Middle Ages there. Danish archaeologist Poul Nörlund dug them up in 1921. The name Herjolfsnes means "Herjolf's Point" or "Cape."

Contents

Founding the Herjolfsnes Settlement

Herjolf Bardsson was one of the main leaders of the Norse colony in Greenland. He was known as "a man of considerable stature." Herjolf joined Erik the Red's journey from Iceland in AD 985. Erik led about 25 ships full of settlers.

Most settlers chose to live further inland, away from the open ocean. This was because the land there was better for farming. But Herjolf decided to settle at the end of a fjord facing the open ocean. This suggests he wanted to build a major port. This port would welcome ships coming from Iceland and Europe.

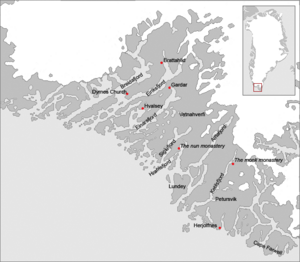

Herjolf's home was on the west side of a fjord named Herjolfsfjord. It was the southernmost main home in the colony's Eastern Settlement.

Herjolfsnes and the Discovery of North America

According to The Greenlanders Saga, Herjolfsnes played a big part in the Norse discovery of North America. Herjolf's son, Bjarni, was doing business in Norway. He returned to Iceland to spend Christmas with his family. But he learned that his father, Herjolf, had gone to the new Greenland colony.

Bjarni set out to follow his father. However, a storm blew his ship off course to the southwest. This made him the first known European to see the coast of North America. Bjarni then sailed back northeast. He found a land that matched the description he had been given. The saga says they landed near a point of land. Bjarni's father lived there, and the place was named Herjolfsnes after him.

Bjarni later told Erik Jarl's court in Norway about his discovery. People at the court criticized him for not exploring the new lands. When Bjarni returned to Herjolfsnes, he stopped sailing. He lived there with his father. After Herjolf died, Bjarni likely became the leader of the settlement.

In Erik The Red's Saga, a famous Icelander named Gudrid Thorbjornsdottir landed at Herjolfsnes after a tough journey. She lived there for a while. This saga mentions a man named Thorkell owning the homestead. It does not mention Herjolf or Bjarni. Some historians believe this was done to make Leif Eriksson seem more important. Leif is known as the first European to land in North America. In The Greenlanders Saga, Leif bought Bjarni's ship to sail to Vinland. He likely got advice and directions from Bjarni.

The Church at Herjolfsnes

After the Norse colony became Christian in AD 1000, Herjolfsnes was one of 16 places in the Eastern Settlement to build a church. The church ruins you see today were built in the 1200s. It was likely built on the site of an older church. It had a rectangular shape, similar to churches at Hvalsey and Brattahlid. This style was common in northern Europe.

The Herjolfsnes church was the third largest in the Norse Greenland colony. Only Gardar and Brattahlid were bigger. Gardar was where the bishop lived and where their parliament met. Brattahlid was important because Erik The Red and his family lived there. The size of the Herjolfsnes church shows how important this settlement was.

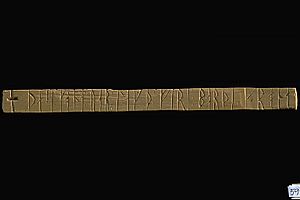

The church's graveyard held the bodies of local people. It also held those who died during ocean voyages to the colony. One story tells of Icelanders who shipwrecked on the east coast in the 1100s. They died trying to cross the glaciers to reach Herjolfsnes. They were buried there instead. For bodies lost at sea, people would carve special messages onto a stick. This stick was then placed in the Herjolfsnes graveyard. One such stick found at Herjolfsnes says, "This woman, whose name was Gudveg, was laid overboard in the Greenland Sea."

Some people at Herjolfsnes were buried in wooden coffins. But wood was scarce. So, people started wrapping the dead in layers of wool clothing. This practice accidentally created a treasure trove of medieval clothes. These well-preserved clothes were found when the graves were dug up in the early 1900s.

Later History of Herjolfsnes

Ivar Bardarson, a Norwegian priest, lived in the colony for almost 20 years in the mid-1300s. He wrote that Herjolfsnes was the main harbor for ships coming to and leaving Greenland. Sailors in the North Atlantic knew it as "Sand." It's not clear if the harbor was right next to the church. Nearby Makkarneq Bay offers better shelter. It has Norse ruins that look like stone warehouses. This might have been the "Sand" harbor Bardarson described.

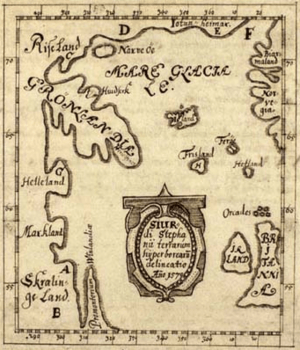

Herjolfsnes is the only Greenland settlement shown on the Skálholt Map. This map from the late Middle Ages shows the coastlines of Europe and North America as seen by Norse explorers.

Contact with Other Peoples

Before the Norse arrived, different groups of Paleo-Eskimo people lived in Greenland. But by the time the Norse came, the island was mostly empty. Only the far northwest might have had people from the Dorset culture. The weather was getting warmer then, which made it hard for the Dorset people to live their hunter-gatherer life. They moved further north.

Because of this, the first Native Americans the Norse Greenlanders met were likely the Beothuk in Newfoundland. Later, the Norse met the Thule culture in Greenland itself. The Thule replaced the Dorset people in the Arctic around AD 1000. These meetings probably started when the Norse went north to hunt for walrus and narwhal ivory.

When the weather got colder during the Little Ice Age, the Thule people moved further south. This led to more contact with the Norse. Modern Inuit Greenlanders have stories about their ancestors meeting the Norse. These stories tell of both friendly times and fights. One legend talks about a Norse leader named Ungortoq and an Inuit leader named K'aissape. K'aissape supposedly burned the Hvalsey settlement. He then chased Ungortoq all the way past Herjolfsnes to Cape Farewell.

Recent soil tests at Makkarneq Bay, near Herjolfsnes, show that both Norse and Thule people lived in the area at the same time. This might mean the Thule were involved in the ivory trade at Herjolfsnes.

The Mystery of Disappearance

The Norse settlements in Greenland lasted for almost 500 years. But we don't know exactly what happened to the people of Herjolfsnes or the rest of the colony. Several things likely played a part. The Little Ice Age made Greenland's climate much colder. This would have made farming very difficult for the Norse settlers.

DNA tests on human remains from Herjolfsnes show that people ate more and more seafood, especially seals. This was different from the farming diet of Erik the Red's time. Other ideas include conflicts with the Thule Inuit or attacks by European pirates. There is no sign that the Norse married the Thule people or adopted their way of life. Also, there are no records from Iceland or Norway about a large group of people leaving Greenland.

Historical records suggest that ships from Europe came less often. This was because sea conditions became worse. The usual Norse route to Greenland was dangerous due to ice. The Norwegian Crown and the Catholic church eventually stopped supporting the colony. By 1448, Pope Nicholas V was sad to hear that Greenland had not had a bishop for 30 years. Pope Alexander VI also believed that no church services had happened in Greenland for a century. He thought no ship had visited for 80 years.

Even after the church stopped supporting the colony, the title "Bishop of Gardar" was still given to many people. But none of them ever visited Greenland.

Although there are no direct accounts of Norse Greenlanders after 1410, the clothes found at Herjolfsnes suggest some people remained. They might have had some contact with the outside world for a few more decades. One sad story is about a sailor called Jon The Greenlander. He got his name because he drifted to Greenland three times. Once, he sailed with German merchants into a deep fjord. They went ashore and found old boat-houses and stone houses. They found a dead man lying face down. He wore a cap and clothes made of wool and sealskin. A worn knife lay beside him. Many believe this happened at or near Herjolfsnes. This dead man might have been the last Norse Greenlander.

Around the same time, Bishop Ögmundur Pálsson reported being blown off course to Greenland. He came close enough to Herjolfsnes to see people tending sheep. This shows that Herjolfsnes remained an important landmark for sailors, even after the Norse were gone.

Early studies of the human remains from Herjolfsnes suggested that the people died out due to inbreeding. But modern scholars disagree. They say the remains show a healthy and successful community. They lived like other people in Northern Europe.

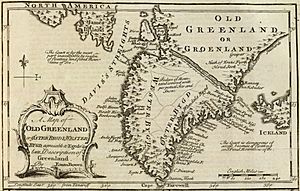

In the 16th century, more explorers and whalers started visiting Greenland. But it wasn't until the early 1700s that Denmark-Norway tried to reconnect with the lost colony. This job was given to Hans Egede. Egede knew the names of the old Norse settlements from sagas. But he didn't know their exact locations. He mistakenly thought that major Eastern Settlement homes like Herjolfsnes were on Greenland's east coast. In reality, all the Norse settlements were on the west coast. Egede spent his life looking for a remaining Norse population on the east coast. Maps from this time often showed Herjolfsnes in the wrong place.

Discovering Norse Clothes at Herjolfsnes

By the early 1800s, visitors and local Inuit found artifacts and clothing pieces near the Herjolfsnes church ruins. The sea level had risen, and the water was eroding the old church grounds. The graveyard was formally rediscovered by Europeans in the early 1800s. A missionary saw that a nearby Inuit house used an old tombstone as a doorway. It had the name Hroar Kolgrimsson on it. A trading clerk also found a Norse wool "sailor's jacket" near the church ruins.

This led to an official excavation in 1839. They found human remains with fair hair, confirming it was a Norse cemetery. More digging in later years revealed more artifacts, human remains, and clothes.

The excavations also found other buildings besides the church. These included the main house, a banquet hall, a barn, and other small buildings. Inside the church ruins, archaeologists found a lot of charcoal. This suggests a big fire happened there. The local Inuit name for the site, Ikigait ("the place destroyed by fire"), also supports this. Other buildings might have been closer to the shore and were lost to the rising sea. More recent tests show a landslide happened in the 1700s. This might have destroyed other Norse buildings.

More and more pieces of wool fabric and clothes were found. People worried that the rising water would soon cover the site. So, the Danish National Museum started an urgent excavation in 1921. It was led by Poul Nörlund. He estimated that the shoreline had moved 12 meters further into the cemetery in less than a century. It was almost touching the church's southern wall. Today, the water level doesn't seem to have risen much since Nörlund's time.

Nörlund wrote in his book, Buried Norsemen at Herjolfsnes, that the local people were very interested in his work. One woman told him she often found pieces of preserved Norse wool. She even made children's clothes from the old fabric. But the wool was not strong enough for practical use. Nörlund and his team worked in tough conditions during the short digging season. They successfully found full and partial costumes, hats, hoods, and stockings. Finding these clothes is considered one of the most important European archaeological discoveries of the 1900s. Before Herjolfsnes, these types of medieval clothes were mostly seen only in old paintings.

Careful study of the clothes showed how skilled the Herjolfsnes people were at spinning and weaving. It also showed they followed European fashions. Later tests using carbon dating suggest that clothes were made at Herjolfsnes as late as the 1430s.

The clothes were stained dark brown from being buried. But tests showed iron on some of them. This iron seemed to have been added on purpose during making the clothes. This suggests that the Herjolfsnes weavers made a red dye from a local mineral. This is believed to be the only known case of medieval Europeans using this mineral to create red dye. They likely did this because they didn't have the madder plant, which was commonly used for red dye in Europe.

The quality and style of the Herjolfsnes clothes make the disappearance of the settlement even more mysterious. As Helge Ingstad noted, "Many of these garments were not worn by common people of Europe, but only by the well-to-do middle class. Altogether the finds testify to a cultivated and fairly prosperous community; certainly not to a people on the brink of extinction."

Else Østergård has also studied the Herjolfsnes clothing in her books, Woven into the Earth and Medieval Garments Reconstructed.

Later Settlement at Herjolfsnes

Archaeologists believe that by the 1500s, the Thule people visited the site. It's not clear if they lived there or just collected iron from the Norse ruins. When Denmark-Norway started recolonizing Greenland in the 1700s, the former site of Herjolfsnes was known as Ikigait by local Inuit.

The Royal Greenland Trading Company had a trading post there from 1834 to 1877. After that, people started moving to nearby Narsarmijit. This left the site empty by 1909. In 1959, a sheep farmer and fisherman named Samuel Simonsen settled Ikigait again. He lived there until he died in 1972. Today, you can see a few modern concrete and wooden foundations in photos of the site. Herjolfsnes / Ikigait is now uninhabited.

Fictional Depiction

In The Greenlanders, a 1988 historical novel by Jane Smiley, Herjolfsnes is shown as being different from other settlements. This is because of its location and its rich inhabitants. They wore special clothes and were proud of knowing more about the outside world.

See also

In Spanish: Herjolfsnes para niños

In Spanish: Herjolfsnes para niños

|

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |