History of Asmara facts for kids

Quick facts for kids UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

|---|---|

| Location | Asmara |

| Part of | Eritrea |

Asmara is the capital city of Eritrea. It became important during medieval times and later. For a long time, it was a major settlement. It was also important because it was on a trade route to Massawa.

In the 20th century, Italy used Asmara as a base. Later, Britain had control, and then Ethiopia. In 1993, Eritrea became an independent country. Even after many years, most of Asmara's buildings look the same. This is partly because it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Asmara was built like a European city. Its planners and builders were mostly European. But local people did the construction work. People in Asmara today are very proud of their city's history.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Asmara comes from "Arbate Asmara." This was the name of a village where Asmara now stands. It means "the women have united the four villages." This name comes from an old story. In the story, women made the men of four villages join together. They wanted to form one big village for safety.

Asmara's Early Days (Before 1922)

Pre-colonial Asmara

The area around Asmara was a great place for a settlement. It had good soil and a mild climate. It also received plenty of rain. Evidence of ancient people has been found nearby.

Old stories say there were once four villages on the Asmara plains. Wild animals and other groups attacked them. So, the women from these villages met to find a solution. They decided not to feed their men until they united the villages. The men agreed, and they built one village called Arbate Asmara.

Asmara was first written about in the late 1300s. An Ethiopian monk called it a "great city" in 1519. A missionary visited in 1751. He noted that a church built by priests 130 years earlier was still standing.

In the mid-1800s, Asmara was a small village with only 150 people. It was close to the coast, so it faced attacks from Egyptians. In 1873, it was "almost deserted." The Ethiopian Emperor Yohannes IV appointed Ras Alula as governor in 1877. Alula made Asmara the capital of the region. Its population quickly grew to over 5,000 people. A busy weekly market brought traders from all around.

Italian Takeover

Italian troops took control of Asmara on August 3, 1889. They built a fort on a hill. At that time, Asmara had 3,000 people. It was made of traditional mud huts. The fort helped the Italians control the local people.

Eritrea officially became an Italian colony in 1890. Massawa was the first capital. Asmara was not chosen then because it wasn't developed enough. It also lacked a good connection to Massawa.

Despite this, Asmara grew in importance. Italy wanted to settle its citizens there. They also wanted Eritrea as a military base. This was for expanding their empire. The population of Asmara first dropped. But it grew a lot when it became the capital. The Massawa-Asmara-Railroad helped Asmara develop.

Becoming a Capital City

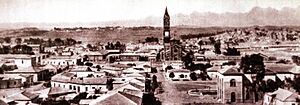

In 1897, Asmara was declared the capital of Eritrea. It had a good military position. It also had better transport links. Before 1900, only a few modern buildings were constructed. These included a police station and a club for Italian officers.

These buildings were in the Mai Bela area. This area had narrow streets. In 1900, a fire destroyed many local homes. This gave Italian planners a chance to rebuild. They wanted to make the city look more European. Early city development focused on an East-West line. This later became the main street, Harnet Avenue.

City Layout

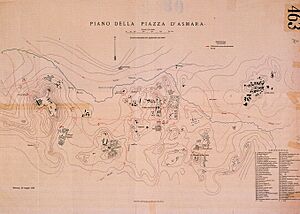

The first city plan for Asmara came out in 1902. It used a grid system for roads. This was a symbol of how the "civilized" Italians brought order. It showed their supposed superiority.

The 1902 plan divided the city into three zones. One zone was for Italians in the city center. Another was for other Europeans, like Greeks and Jews. A third zone was for local people. This zone was unplanned and outside the northern city border. A fourth zone for industry was added in 1908. Later plans made this racial separation even stricter.

Asmara was meant to be a new home for skilled Italian workers. The European quarter had wide, tree-lined streets. Houses were built with space between them. Asmara truly became an Italian city.

Local Eritreans who owned property in the city center were forced to move. In 1908, a rule said the first zone was only for Italians and other Europeans. Local people, called "colonial subjects," could only live in the indigenous quarter. Only Askari, local soldiers working for the Italians, could live near Italian homes. This showed the Italians trusted these soldiers.

These early plans led to a lot of building. Asmara's population grew from 800 to over 8,500 by 1905. About 1,500 of these were Europeans. This growth brought more trade and jobs. Many important buildings were built. These included the Governor's Palace, the first Italian school, and the cathedral. The Massawa-Asmara-Railroad Line was finished in 1911.

Asmara Under Mussolini (1922–1941)

Fascist Development

When Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922, Asmara changed again. During his rule, the city saw its biggest building boom. Mussolini wanted to build an Italian empire. So, Asmara became very important in Italian East Africa.

The major building boom started around 1935. Before that, Asmara was mostly military bases and a small town. In the 1920s, Asmara had about 18,000 people. About 3,000 were Italians. Building focused on offices and homes for leaders.

Modern architecture slowly came to Eritrea in the 1920s. In Italy, a new style called Rationalismo developed in 1927. Before 1935, most buildings in Asmara used older Italian styles. For example, Asmara's theater used Romantic and Renaissance styles. The Bank of Eritrea building was Neo-Gothic. Most of the truly modern buildings were built between 1935 and 1941.

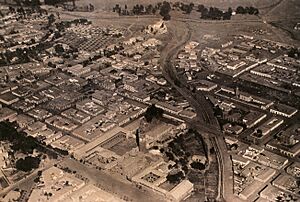

At the start of the 20th century, people in Asmara were separated by race. Mussolini's plans made this separation even stronger. By 1930, the city was divided into four clear zones. There was a zone for local people in the north. An industry zone had diagonal blocks. The "Villa quarter" was for Europeans. And a mixed zone was around the market. This mixed zone had offices and shops for everyone. It also had cultural places. This separation of people by race was very strict under fascism.

Growth as a Military Base

Italy planned to invade Ethiopia. So, Asmara's look began to change. More soldiers came to Eritrea. The city's population grew very fast. Between 1932 and 1936, it jumped from 18,000 to 98,000 people. Asmara became a busy administrative and trading city. It needed more housing, businesses, and services.

In 1935, Italy invaded Ethiopia without warning. Asmara was a perfect military base. It had a good climate for Europeans and a strategic location. So, Asmara became the main supply base for the Abyssinian War. Italy used many soldiers and aircraft. They also had support from 60,000 Askari soldiers. The war was very bloody.

After winning the war in May 1936, Italy's African colony grew huge. It included Eritrea, Ethiopia, and parts of Somalia. It became the third-largest colonial empire. Mussolini ordered new roads to be built. This was a time for city planning and design.

Italian East Africa became a "playground for architects." Italy wanted to settle millions of Italians there. This needed huge infrastructure plans. Streets, offices, and homes had to be built. Architects and planners were eager to work there.

Strict Segregation Policies

In 1936, it was announced that architects in the colonies must support fascist ideas. One architect, Carlo Quadrelli, said that white people were rulers. They should have all privileges. Laws should be different for whites and locals. White people's houses were top priority. Locals' homes were only important if they helped whites. Whites and people of color should not live in the same house. White homes should have the best comforts.

Even famous architect Le Corbusier wanted to build in East Africa. He suggested a main road to separate Europeans from locals. This plan ignored local traditions.

The strict separation of races was followed. City planners wanted to put fascist ideas into the cities. They didn't care about existing structures. They saw East Africans as "barbarians." They believed these people didn't have real cities or culture. To create their empire, planners destroyed historical areas.

From 1935 to 1940, the "Africa Orientale Italiana" project cost a lot of money. This showed how important the colony was to Mussolini. Asmara became a symbol of colonial success. It was a platform to show Italian power.

Building Boom

After 1936, cities in East Africa saw a huge building boom. Asmara grew faster than any other city. The years up to 1941 were the most important for Asmara's development.

Many workers came to Asmara to build new structures. There was endless work from 1935 to 1941. At first, locals only did simple tasks. But later, more locals were hired because European workers were too expensive. Italy's government paid for most of the construction. Asmara became known as "Piccola Roma" (Little Rome). A 1938 guide called it the most graceful Italian city.

In Asmara, old local huts were torn down for new buildings. Only in the official local settlement in the north did these huts remain. After many huts were destroyed, 45,000 local residents moved to the "citta indigene" (indigenous city).

Architects of the "New Building Movement" wanted cities to fit the machine age. They criticized the disorder of cities. They believed this disorder harmed people's health. In Asmara, this meant pushing for full racial segregation. With locals moved out, developers had more space. Italian architects designed new, modern buildings. They broke away from traditional Italian and African styles.

After the war with Ethiopia ended, Italians focused on civilian buildings. Soldiers and craftsmen brought their families. So, the city needed more schools and housing. Racial segregation policies became clearer. This was common for all European colonial powers in Africa.

Radical Separation Policies

Italian plans aimed to give Italians in Asmara modern European living standards. They also promised some improvement for Eritreans. But Eritreans' starting conditions were very low.

Asmara had grown fast, so restructuring it was hard. To separate races, existing zones were used. The mixed market area became a buffer zone. It separated local settlements in the north from European areas in the south and west. This buffer zone was the only place where white and black people could meet. But only educated Eritreans were allowed access. A green stripe was painted along what is now Segeneyti Street. This was another barrier locals couldn't cross.

Not just homes were separated by race. Restaurants, theaters, hospitals, and churches were also segregated. Sometimes, even different entrances were used. Eritreans' access to schools was limited. Black children could only attend school for three years. There were no other schools for them.

Living conditions for Eritreans in Asmara were poor. Their quarters were ignored by planners. There were no modern buildings there. Roads were unpaved. Electricity and water didn't reach these areas. There was no good infrastructure for health or education. Meanwhile, Italians lived just meters away. By 1941, European zones had water and sewer systems. They had good medical care. Their streets were tree-lined and patrolled by police.

Architectural Styles

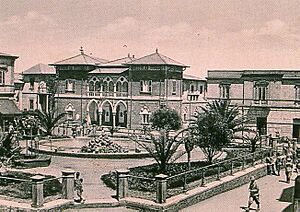

Italians designed Asmara to fit their ideas. The city had many cinemas. These included Cinema Impero (1937) and Cinema Roma (1937). All these cinemas were only for Europeans. But locals also got their own cinema, Cinema Hamasien, built in 1936. More leisure activities for Italians appeared. These included golf courses and tennis clubs.

Motorsport events were popular. Many Italian cars were sent to Eritrea. By 1938, Asmara had about 50,000 cars. This was more traffic than in Rome. Car companies built impressive offices in Asmara. Architects designed modern buildings for companies like Agip and Fiat. Asmara was a place for new and experimental architecture.

Not all buildings were commissioned by Mussolini. Private people and industries owned many buildings. The Fiat Tagliero petrol station (1938) is famous. It looks like an airplane with concrete wings. Airplanes symbolized progress and speed at that time.

Other buildings also showed progress. The Shell Service Station (1937) looked like a ship. The Bar Zilli building looked like a 1930s radio. The former Fascist Party headquarters looked like an "F" for Fascismo.

Italian architects designed buildings that showed progress. Unlike in Italy or Nazi Germany, Asmara didn't have huge, monumental buildings. But the city's architecture still showed fascist ideas. It showed the Italians' supposed superiority over Eritreans. Mussolini liked modern architecture, speed, cars, and airplanes. This was reflected in many of Asmara's buildings.

Between 1935 and 1941, many buildings were constructed. They followed the Rationalismo style. These buildings ranged from small apartments to large office buildings. They were simple and lacked extra decoration.

The colonial government also built roads and squares. These showed the power of the fascist regime. Viale Mussolini (now Harnet Avenue) and Piazza Roma (now Post Square) were built for parades. Viale Mussolini was the city center. It had offices, cinemas, and shops. Italians used it for walks. But local people were not allowed on this street.

More and more Italians moved to Asmara. In 1939, 98,000 people lived there. 53,000 were Italians. Most people were Christian. Many spoke Italian.

But this growth stopped. During World War II, Italy lost to the British in 1941. Mussolini never visited Eritrea. The British were impressed by Asmara. They called it a European city with wide streets and great buildings. With the British takeover, the building boom ended.

Asmara today has many unique modern buildings. They show Italian modernist architecture from the 1920s and 1930s. The avant-garde buildings from 1935 to 1941 are especially impressive. But the strict racial segregation policies of that time are also part of Asmara's history.

British Military Administration (1941–1952)

Under British Control

On April 1, 1941, Italy's dream of an ideal colony ended. The British took control of Eritrea. This was called the British Military Administration (BMA). The BMA's job was to manage the colony's transition. The British occupation didn't change Asmara's buildings much. But it started Eritrea's 50-year fight for independence. This fight greatly shaped the identity of Asmara's people.

The British Empire didn't want to keep Eritrea as a separate colony. They wanted to divide it. The highlands were to go to British Sudan. The lowlands were to go to Ethiopia. The British had few officers to manage Eritrea. So, Italian administrators mostly stayed in charge, supervised by the British.

Eritreans in Asmara suffered from shortages. They lived in poor conditions. They also had to take in people displaced from other parts of Eritrea. The British did not help them much. The British also used a "divide and conquer" strategy. They encouraged political divisions among Eritreans. This stopped people from making decisions together.

The British administration also dismantled the country. They sold factories and equipment. They sent them to other British colonies. For example, parts of the Massawa-Asmara railway were sent to Sudan and India. Despite these losses, Asmara remained an important trading center.

Ending Racial Segregation

The British partly ended racial separation. For the first time, Eritreans could join a training program for civilian administration. The first Eritrean teacher schools were set up. By 1943, schools were open to local children. Under Italian rule, Eritrean children couldn't go to elementary schools. A secret school was even hidden in a church bell tower. By 1954, the British had built over 100 schools for locals. They also started a public press in Tigrinya, Arabic, and English.

An example of ending segregation happened in 1943. Eritrean workers couldn't find seats on a bus. So, they took seats usually reserved for Italians. This caused a fight. The British administrator said he couldn't change Italian laws. But he suggested Eritreans organize their own transport. The locals quickly bought a truck and added benches. The Italian bus owner lost business and had to sell his bus to the Eritreans. Now, the Eritrean workers had their own bus and free seats.

British Repression

After World War II, Eritrea faced a crisis. Unemployment rose. Italians received aid, but locals struggled. They tried to reclaim their land. This caused deep anger among Eritreans. Many felt the British were worse than the Italians. The BMA often broke promises. They fined Eritreans for peaceful protests. This led to more riots.

Most Eritreans wanted freedom and independence. But their voices were split. Some wanted to separate, others wanted to join Ethiopia. By 1949, about 75% of Eritreans supported independence.

In 1952, an Eritrean group went to the UN. They heard that Eritrea might be given to Ethiopia. Ethiopia's leader, Haile Selassie, had built strong ties with the US. He sent troops to the Korean War. He also let the US build a military base in Eritrea. The US saw Eritrea as strategically important. They believed it should be linked with Ethiopia. So, Eritrea became an Ethiopian province.

Ethiopian Rule and War (1952–1993)

Losing its Capital Status

For 70 years, two ideas shaped the view of Ethiopia and Eritrea. First, that Eritrea was naturally part of Ethiopia. This was based on shared history, religion, and culture. Also, Eritrea gave Ethiopia access to the sea. Second, that Eritrea was too weak to survive alone. World powers like the US and Britain supported this. They wanted to meet their own strategic needs. So, the UN decided Eritrea would join Ethiopia as an autonomous region. This was against the will of the people.

Asmara lost its title as capital. It slowly became a provincial town. While Asmara didn't change much physically, Eritreans' identity shifted. They struggled under new foreign rule. The 40 years from 1952 to independence in 1991 were very important.

Ethiopia used Federalism to its own benefit. It gave Eritrea no room to develop. Ethiopian officials took over most administrative jobs. The Ethiopian military was also present. Customs, postal services, and railways were all run by Ethiopians.

Stagnation in Development

Ethiopian officials in Addis Ababa made stricter laws. Eritrean political parties were banned. Eritreans couldn't collect their own taxes. Newspapers were censored. Early in Selassie's rule, some churches, mosques, and schools were built in Asmara. But later, there was little investment. Industries declined. Many factories were moved to Addis Ababa. This weakened Eritrea's economy.

In 1959, Tigrinya and Arabic were banned in schools. Amharic became the language of instruction. This made education hard for many Eritreans. Student protests were met with violence. A general strike in 1958 led to deaths and injuries. Many Eritreans were arrested or forced to leave. Appeals to the United Nations were ignored.

Street names in Asmara were also changed. This was to erase the Italian past. For example, Viale Mussolini became Haile Selassie I Boulevard. This showed Ethiopia's control over the city's identity.

Annexation and Resistance

Haile Selassie openly said Ethiopia was interested in the land, not the people. Ethiopian troops burned villages and killed people. In 1960, Eritrea's government was downgraded. In 1962, Ethiopia ended the federation. Ethiopia besieged Asmara. It forced the Eritrean parliament to dissolve. Then, Ethiopia annexed all of Eritrea. Eritrean leaders decided armed struggle was the only way to resist.

In 1974, Haile Selassie was overthrown. The resistance movement fought Ethiopia's army. It also had internal conflicts. The Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) was founded around 1970. It united many fighters. Their main goal was independence. This unity helped Eritreans fight. People from all religions joined the movement.

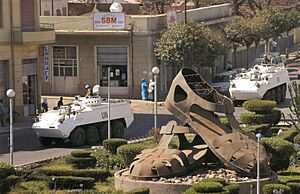

The Derg, Ethiopia's military government, continued similar policies. But they were more brutal. They had support from the Soviets and Cubans. Asmara became a military camp. Ethiopian army divisions occupied districts. Italian buildings were turned into prisons. Yet, Asmara's importance as a trade center grew. It remained mostly unharmed. Building activity slowly recovered. This included new high-rise buildings. The monumental stadium on Bahti-Meskerem Square was also built.

Independence from Ethiopia

In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union stopped supporting Ethiopia. Without Soviet help, and with drought and economic crisis, Ethiopian soldiers lost morale. The EPLF gained ground. In May 1991, the Derg regime fell. The EPLF and Ethiopia's new government agreed to a vote on independence. An overwhelming 99.83% of Eritreans voted for independence. On May 24, 1993, Eritrea became an independent country. Isayas Afewerki, head of the EPLF, became president.

The armed conflict lasted almost 30 years. It showed human resistance. But it also caused terrible loss for two poor countries. Eritreans fought mostly alone against a stronger Ethiopian army. Even though Eritreans came from different tribes and religions, they united. They achieved independence. Asmara survived the war almost untouched. Its people today say, "Asmara is what we fought for."

Asmara After Independence (1993–Present)

Post-War Period

Over 50 years had passed since Italian planners were last active. After British and Ethiopian rule, and 30 years of war, Eritrea was finally free. Asmara saw little fighting within its limits. But the city was in bad shape. Residents remember boys and girls carrying water barrels. Buildings had military defenses. Windows were broken. There was a bad smell from clogged sewers. Many beggars showed widespread poverty. Buildings were decaying. Asmara's basic infrastructure needed a complete overhaul. The city was joyful about freedom, but also in ruins.

Return as Political Capital

The population grew as refugees returned. Asmara became the political heart of Eritrea again. In the following years, Eritrea's economy improved. Many investments came in. This led to Asmara's dramatic growth. Unlike other African cities, Asmara's development was controlled. But challenges remained. People needed clean drinking water. The sewage system was still in ruins.

After decades of foreign rule, people wanted to develop their own way. A debate started about Asmara's colonial architecture. For the first time, Asmara's city center was seen as having a valuable history. People saw the Italian buildings as a reminder of their country's past. Asmara's citizens fought to save old buildings. They didn't want to erase history by tearing them down. For example, a plan to build an office building was stopped by citizens.

Preservation Efforts

People knew Asmara's city center should be saved. But it also needed to meet the community's needs. In 1997, the Eritrean government started the Cultural Assets Rehabilitation Project (CARP). This project aimed to preserve Asmara's architecture. In 2001, an area of about 4 square kilometers was protected. The goal was to make this unique urban area a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A map of Asmara was made to help tourists. A book, Asmara: Africa's Secret Modernist City, was published in 2003. It brought worldwide interest to Asmara's architecture. However, the CARP project was later stopped by the government.

Eritrea has become a more controlled state. President Isayas Afewerki is at the center. Early steps towards democracy in the 1990s seemed to legitimize the leaders. Eritrea still doesn't have a working constitution.

Since the 1998-2000 border war with Ethiopia, Eritrea has been in a state of emergency. Citizens live under military law. There is no freedom of speech or press. The country relies on national service, often for life.

Financial Support for Historic Core

President Afewerki has a strict policy of self-sufficiency. He rejects foreign aid. For example, in 2007, he turned down $200 million in relief aid. This makes it hard to care for Asmara's heritage. Eritrea is one of the poorest nations. It cannot do this alone. The CARP project, with its $5 million budget, was abandoned. Other programs to preserve Asmara's city center are not active. It is hard to imagine Afewerki accepting foreign help for these programs.

In 2017, the historical core of Asmara was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

See also

- Timeline of Asmara

- History of Eritrea

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |