History of Eritrea facts for kids

Eritrea is an ancient name, linked to the Greek word Erythraia, which means "red." This name is connected to the Red Sea, which was once called the Erythræan Sea. Long ago, Eritrea was also known as Hamasien. In the 1800s, the Italians created the colony of Eritrea around Asmara and gave it its current name. After World War II, Eritrea became part of Ethiopia. In 1991, a group of armed forces defeated the Ethiopian government. Eritrea then declared its independence and celebrated its first anniversary on May 24, 1994.

Contents

Prehistory

Scientists found one of the oldest human ancestors in Buya, Eritrea. This discovery is over 1 million years old and shows a possible link between early humans like Homo erectus and Homo sapiens. Experts believe the Danakil Depression in Eritrea was also important for human evolution. It might hold more clues about how early humans developed.

During a warm period long ago, early modern humans lived along the Red Sea coast of Eritrea. This area might have been a path early humans used to travel out of Africa and settle in other parts of the world. In 1999, scientists found a Paleolithic site near the Gulf of Zula, south of Massawa. They found stone and obsidian tools that are over 125,000 years old. These tools were likely used by early humans to gather food from the sea, like clams and oysters.

Experts who study languages believe that the first people who spoke Afroasiatic languages arrived in this region during the Neolithic era. They might have come from the Nile Valley. Other experts think these languages developed right here in the Horn of Africa, and then their speakers spread out from there.

Antiquity

Punt

Eritrea, along with Djibouti, northern Somalia, and parts of Sudan, is thought to be the ancient land of Punt. The Ancient Egyptians knew about Punt as early as 2500 BC. The people of Punt had close ties with Egyptian pharaohs like Sahure and Hatshepsut.

In 2010, scientists studied the mummified remains of baboons that were brought from Punt to ancient Egypt. By examining the baboons' hair, researchers found that the mummies' oxygen levels matched modern baboons from Eritrea and Ethiopia. This suggests that Punt was likely a narrow area that included parts of northern Ethiopia, northeastern Sudan, northern Somalia, and all of Eritrea.

Ona Culture

Digs in Sembel near Asmara show signs of an ancient civilization called the Ona culture. This culture existed before the Kingdom of Aksum. The Ona people are believed to be among the first farming and herding communities in the Horn of Africa. Artifacts found at the site date back to between 800 BC and 400 BC. This was around the same time as other early settlements in the Eritrean and Ethiopian highlands.

The Ona culture might have also been connected to the land of Punt. In an ancient Egyptian tomb, pictures show long-necked pots, similar to those made by the Ona people, being brought from Punt on a ship.

Gash Group

Excavations near Agordat in central Eritrea uncovered remains of another ancient civilization called the Gash Group. They found pottery similar to that of the Nubian C-Group culture, which lived in the Nile Valley between 2500 and 1500 BC. Pottery like that of the Kerma culture, another Nile Valley community from the same period, was also found in the Barka valley.

Kingdom of D'mt

D'mt was an ancient kingdom that covered most of Eritrea and northern Ethiopia. It existed during the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Its capital was probably Yeha, where a large temple complex was found. Important D'mt cities in southern Eritrea included Qohaito and Matara. There are many other Ancient cities in Eritrea.

This kingdom developed ways to water their crops, used plows, grew millet, and made iron tools and weapons. After D'mt fell around 500 BC, smaller kingdoms took over. Then, in the first century AD, the Kingdom of Aksum rose and brought the area back together.

Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum was a powerful trading empire located in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia. It lasted from about 100 AD to 940 AD. It grew from an earlier Iron Age period around 400 BC.

The Aksumites started in the northern highlands of the Ethiopian Plateau and expanded south. A Persian religious leader named Mani listed Aksum as one of the four great powers of his time, alongside Rome, Persia, and China. The exact beginnings of the Aksumite Kingdom are not fully clear.

The Aksumites built many large stone pillars called stelae. These had a religious purpose before Christianity arrived. One of these granite columns is the tallest in the world, standing at 90 feet. Under Ezana (who ruled around 320–360 AD), Aksum adopted Christianity. In 615 AD, during the time of Muhammad, the Aksumite King Sahama gave shelter to early Muslims from Mecca who were facing persecution. This event is known as the First Hijra in Islamic history. The area is also believed to be where the Ark of the Covenant rests and the home of the Queen of Sheba.

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mentions Aksum as an important place for ivory trade. Aksumite rulers made their own Aksumite currency to help with trade.

The kingdom also gained control over the declining Kingdom of Kush and often got involved in the politics of kingdoms on the Arabian peninsula. They even extended their rule over the Himyarite Kingdom. Coins showing royal portraits began to be made under King Endubis in the late 200s AD.

Expeditions by Ezana into the Kingdom of Kush in Sudan might have led to its downfall. Aksum bordered the Roman province of Egypt because of Ezana's expansions.

Post-classical period

Early developments

From the late 1000s to the early 1100s, many groups of people moved into Eritrea. After the Aksum kingdom declined in the late 600s, large parts of Eritrea were taken over by the Beja. They are believed to have founded several kingdoms. The Beja rule ended in the 1200s, and they were pushed out of the highlands by settlers from Abyssinia (Ethiopia).

Another group, the Bellou, appeared in the 1100s and controlled parts of northwestern Eritrea until the 1500s. After 1270, many Agaw people fled to Eritrea after the Zagwe Kingdom was destroyed. Most of them blended into the local Tigrinya culture. The Cushitic-speaking Saho also arrived after Aksum fell and settled in the highlands by the 1300s.

During this time, Eritrea slowly began to convert to Islam. Muslims first arrived in Eritrea in 613/615 AD. In 702 AD, Muslim travelers reached the Dahlak islands. In 1060, a Yemeni family fled to Dahlak and created the Sultanate of Dahlak, which lasted for almost 500 years. This sultanate also controlled the port town of Massawa.

12th century to the Italian arrival

The 12th century saw the rise of a new kingdom called Medri Bahri. This area was previously known as Ma'ikele Bahr ("between the seas/rivers"). During the rule of Emperor Zara Yaqob, it was renamed Medri Bahri ("Sea land" in Tigrinya). Its capital was Debarwa, and its main areas were Hamasien, Serae, and Akele Guzai. In 1879, Medri Bahri was taken over by Ras Alula, who defended the area against the Italians until they finally occupied it in 1889.

The Ottoman Empire tried to expand further inland in the 1500s, conquering Medri Bahri. The Ottomans only had weak control over much of the territory for centuries until it was re-conquered in the 1800s.

In southern Eritrea, the Aussa Sultanate (Afar Sultanate) took over from an earlier state in 1577. In 1734, the Afar leader Kedafu started the Mudaito dynasty. This began a new, more organized state that lasted until the colonial period.

Italian Eritrea

Establishment

The borders of modern-day Eritrea were set during the "Scramble for Africa" when European powers divided up the continent. Around 1869 or 1870, the Sultan of Raheita sold land near the Bay of Assab to an Italian shipping company. This area became a place for ships to refuel after the Suez Canal was built. Italian settlers first arrived in 1880.

Later, as the Egyptians left Sudan during a rebellion, the British helped them retreat through Ethiopia. In exchange, the British gave the port of Massawa to the Italians. The Italians combined Massawa with the port of Asseb to form a coastal Italian possession. In 1889, after the death of Emperor Yohannes IV, the Italians took advantage of the chaos in northern Ethiopia. They occupied the highlands and established their new colony, called Eritrea. Ethiopia's new Emperor, Menelik II, recognized this.

The Italian control of coastal areas was made official in 1889 with the Treaty of Wuchale. Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia recognized Italy's control over lands like Bogos, Hamasien, Akkele Guzay, and Serae. In return, Italy promised financial help and access to European weapons. Menelik later said he was tricked by translators into agreeing that all of Ethiopia would become an Italian protectorate. However, he had to accept Italian rule over Eritrea.

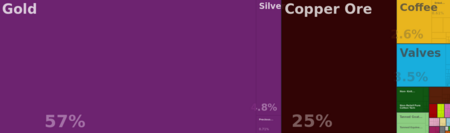

In 1888, the Italian government started its first development projects in the new colony. The Eritrean Railway reached Saati in 1888 and Asmara in 1911. The Asmara-Massawa Cableway was the longest of its kind in the world when it opened in 1937. The British later took it apart after World War II as war reparations. Besides big building projects, the Italians invested a lot in farming. They also provided city services in Asmara and Massawa and hired many Eritreans for public jobs, especially in the police and public works. Thousands of Eritreans also joined the army and fought in wars in Libya and Ethiopia.

The Italian administration also opened many factories that made buttons, cooking oil, pasta, building materials, and other goods. By 1939, there were about 2,198 factories, and most workers were Eritrean. The growth of industries led to more Italians and Eritreans living in cities. The number of Italians in Eritrea grew from 4,600 to 75,000 in five years. Eritreans also became involved in trade and farming.

In 1922, Benito Mussolini came to power in Italy, bringing big changes to Italian Eritrea. After he declared the Italian Empire in May 1936, Italian Eritrea (which included parts of northern Ethiopia) and Italian Somaliland were combined with Ethiopia to form the new Italian East Africa. This period was about expanding the empire. Eritrea was chosen to be the industrial center of Italian East Africa. After a fight by the Eritreans, the Italians left Eritrea.

The Italians also brought a lot of Catholicism to Eritrea. By 1940, almost one-third of the population was Catholic, mostly in Asmara, where several churches were built.

Asmara development

Italian Asmara had a large Italian community, and the city began to look very Italian. One of the first buildings was the Asmara President's Office, built in 1897 by Ferdinando Martini, the first Italian governor. The Italian government wanted an impressive building in Asmara to show Italy's dedication to its "first daughter-colony," Eritrea.

Today, Asmara is famous worldwide for its early 20th-century Italian buildings. These include the Art Deco Cinema Impero, the "Cubist" Africa Pension, the Orthodox Cathedral, the futurist Fiat Tagliero Building, and the neo-Romanesque Church of Our Lady of the Rosary, Asmara. The city has many Italian colonial villas and mansions. Most of central Asmara was built between 1935 and 1941, meaning the Italians built almost an entire city in just six years.

In 1939, the city of Italian Asmara had 98,000 people, with 53,000 of them being Italians. This made Asmara the main "Italian town" in Italy's African empire. In all of Eritrea, there were 75,000 Italian Eritreans that year.

Many factories were built by Italians in Asmara and Massawa. However, the start of World War II stopped Eritrea's growing industries. During the Allied efforts to capture Eritrea from the Italians in 1941, much of the infrastructure and factories were badly damaged.

The Italian guerrilla war was supported by many Eritrean colonial troops until Italy surrendered in September 1943. Eritrea was then placed under British military control after World War II.

The Italian Eritreans strongly opposed Ethiopia taking over Eritrea after the war. The Party of Shara Italy was formed in Asmara in July 1947. Most of its members were former Italian soldiers and many Eritrean Ascari. This party, led by Dr. Vincenzo Di Meglio, helped stop a plan to divide Eritrea between Sudan and Ethiopia in 1947.

The main goal of this Italian-Eritrean party was Eritrea's freedom. But they had a condition: before independence, the country should be governed by Italy for at least 15 years, similar to what happened with Italian Somalia.

British administration and federalisation

Quick facts for kids

British Military Administration in Eritrea

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941–1952 | |||||||||

|

Flag

|

|||||||||

| Government | Military administration | ||||||||

| Military Administrator | |||||||||

|

• 1941–1942

|

William Platt | ||||||||

|

• 1942–1944

|

Stephen Longrigg | ||||||||

|

• 1944–1945

|

Charles McCarthy | ||||||||

| UN High Commissioner | |||||||||

|

• 1951–1952

|

Eduardo Anze Matienzo | ||||||||

| Chief Administrator | |||||||||

|

• 1951–1952

|

Duncan Cumming | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 19 May 1941 | |||||||||

|

• UN supervision

|

19 February 1951 | ||||||||

|

• Eritrean Autonomous State

|

15 September 1952 | ||||||||

| Currency | pound | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

British forces defeated the Italian army in Eritrea in 1941. They then placed the colony under British military control until the Allied forces could decide its future. Some Italian-built structures and factories were taken apart and moved to Kenya as war reparations.

Since the Allies couldn't agree on Eritrea's status, the British military continued to govern until 1950. After the war, the British suggested dividing Eritrea based on religion. They thought the Muslim population could join Sudan and the Christians could join Ethiopia. Some Arab states wanted Eritrea to be an independent country because of its large Muslim population.

There were some conflicts between Christians and Muslims in Asmara, Eritrea. One notable event happened in February 1950. When a UN Commission arrived to investigate Eritrea's future, actions by supporters of the Unionist Party increased. They tried to stop people who wanted independence from meeting with the UN Commission. They also targeted transportation and communication systems.

A local Muslim leader, Bashai Nessredin Saeed, was killed on February 20 while praying. People believed he was killed because he refused to leave the Muslim League and join the Unionist Party. This killing caused strong reactions among Muslims in Asmara. A large funeral procession was held, and it passed by the Unionist Party office. According to reports, members of the Unionist Party began throwing stones and grenades at the procession, leading to open conflict. Many people were killed and injured on both sides. The police intervened, but the fighting continued and spread to other areas. Properties were also looted and burned.

The British Military Administration declared a curfew. The administrator called a meeting with religious leaders, including the Mufti and Abuna Marcos, asking them to help calm the people. They agreed and visited different districts, speaking to people through microphones in Arabic and Tigrinya, urging them to end the violence. The wise leaders from both sides accepted the call, but looting continued for three more days before the riots ended. On February 25, both Christian and Muslim communities met and agreed to take an oath to prevent further violence. They formed a committee to oversee the agreements. More than 62 people were killed, and over 180 were injured. The damage to properties was extensive. The riots, which some believed were influenced by external parties, were eventually stopped by the efforts of religious leaders and elders.

Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie wanted to expand his empire and claimed Italian Somaliland and Eritrea. He made this claim to the United States and the United Nations. The United States and the United Kingdom supported giving most of Eritrea to Ethiopia as a reward for its help in World War II. However, Eritrean parties who wanted independence asked the UN General Assembly for a referendum to decide their future.

A United Nations (UN) commission went to Eritrea in February 1950. The US Ambassador to the UN, John Foster Dulles, said that while the Eritrean people's wishes should be considered, the US's strategic interests in the Red Sea made it necessary for Eritrea to be linked with Ethiopia. This showed that Eritrea's desire was for independence.

The UN commission suggested that Eritrea form some kind of association with Ethiopia. On December 2, 1950, the UN General Assembly adopted this idea. It also stated that the British military administration of Eritrea would end by September 15, 1952. The British held elections for a Legislative Assembly in March 1952. This assembly then accepted a draft constitution. On September 11, 1952, Emperor Haile Selassie approved the constitution. The Representative Assembly became the Eritrean Assembly. In 1952, a UN resolution to join Eritrea with Ethiopia in a federation went into effect.

This resolution ignored Eritrea's wish for full independence. However, it promised the people some democratic rights and self-rule. Some experts thought this was a religious issue, with Muslims wanting independence and Christians wanting to join Ethiopia. But others, like Bereket Habte Selassie, argued that most Eritreans (both Christians and Muslims) wanted freedom and independence.

Soon after the federation began, these rights were taken away. Eritreans asked for a referendum on independence, and a confidential American memo estimated that about 75% of Eritreans supported independence.

The UN resolution said Eritrea and Ethiopia would be loosely linked under the Emperor's rule. Eritrea would have its own government, laws, flag, and control over its local affairs, including police and taxes. The federal government (Ethiopia's government) would control foreign affairs, defense, money, and transportation. Eritreans had a strong sense of their own culture and wanted political freedoms that were new to Ethiopian traditions. This is why the British left and Eritreans fought for their rights.

From the start, Haile Selassie tried to weaken Eritrea's independent status. He forced Eritrea's elected leader to resign, made Amharic the official language instead of Arabic and Tigrinya, stopped the use of the Eritrean flag, and moved many businesses out of Eritrea. Finally, in 1962, Haile Selassie pressured the Eritrean Assembly to end the Federation and join Ethiopia completely. This upset many Eritreans who wanted a more liberal political system.

War for independence

People began to oppose Eritrea becoming part of Ethiopia in 1958. This was when the Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM) was founded by students and workers. The ELM worked secretly to build resistance against Ethiopia's centralizing policies. However, by 1962, the ELM was discovered and stopped by Ethiopian authorities.

Emperor Haile Selassie dissolved the Eritrean parliament and illegally annexed the country in 1962. The war continued even after Haile Selassie was removed from power in 1974. The new Ethiopian government, called the Derg, was a Marxist military dictatorship led by Mengistu Haile Mariam.

In 1960, Eritrean exiles in Cairo founded the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF). This group led the fight for Eritrean independence in the 1960s. Unlike the ELM, the ELF immediately started an armed struggle. The ELF was mostly made up of Eritrean Muslims from the western lowlands. Radical Arab states like Syria and Iraq saw Eritrea as a Muslim region fighting Ethiopian oppression. They gave military and financial help to the ELF.

The ELF started military actions in 1961 and increased them after the federation ended in 1962. By 1967, the ELF had strong support among farmers, especially in northern and western Eritrea, and around Massawa. Haile Selassie tried to calm the unrest by visiting Eritrea and promising equal treatment. However, Ethiopia's secret police also set up many informants and carried out disappearances and killings among the people. The imperial army also committed massacres until the Emperor was overthrown in 1974.

By 1971, the ELF's activities were such a threat that the emperor declared martial law in Eritrea. He sent about half of the Ethiopian army to fight the ELF. Disagreements within the ELF led to its split, and the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) was formed in 1972. This new group was led by leftist, Christian Eritreans who spoke Tigrinya, Eritrea's main language. There were fights between the two Eritrean groups from 1972 to 1974, even as they both fought Ethiopian forces. By the late 1970s, the EPLF became the main Eritrean group fighting Ethiopia. Isaias Afewerki became its leader. Much of the weapons used by the EPLF were captured from the Ethiopian army.

By 1977, the EPLF seemed ready to push the Ethiopians out of Eritrea. However, that same year, the Soviet Union sent a huge amount of weapons to Ethiopia. This allowed the Ethiopian Army to regain strength and forced the EPLF to retreat. Between 1978 and 1986, the Ethiopian government launched eight major attacks against the independence movement, but they all failed. In 1988, the EPLF captured Afabet, the Ethiopian Army's headquarters in northeastern Eritrea. This put about a third of the Ethiopian Army out of action. EPLF fighters then moved near Keren, Eritrea's second-largest city. By the end of the 1980s, the Soviet Union stopped its support to Ethiopia. With less support, the Ethiopian Army's morale dropped, and the EPLF, along with other Ethiopian rebel forces, began to advance.

Provisional Government and People's Front for Democracy and Justice

The United States helped with peace talks in Washington before the Mengistu government fell in May 1991. In mid-May, Mengistu resigned and went into exile. EPLF troops took control of Eritrea after defeating Ethiopian forces. Later that month, the United States led talks in London to officially end the war. The EPLF attended these talks.

After the Mengistu government collapsed, Eritrea's independence gained support from the United States. The EPLF, which had once had some Marxist ideas, changed its views after the fall of communist governments in the Soviet Union. The EPLF now says it wants to create a democratic government and a free-market economy in Eritrea. The United States agreed to help both Ethiopia and Eritrea, as long as they continued towards democracy and human rights.

In May 1991, the EPLF set up the Provisional Government of Eritrea (PGE) to manage affairs until a vote on independence and a permanent government were established. EPLF leader Afewerki became the head of the PGE.

Eritreans voted overwhelmingly for independence between April 23 and 25, 1993, in a UN-monitored referendum. The result was 99.83% in favor of independence. Eritrea officially became an independent state on April 27, 1993. The government was reorganized, and the National Assembly included both EPLF and non-EPLF members. The assembly chose Isaias Afewerki as president. The EPLF then became a political party called the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ).

After independence

The first President of Eritrea, Isaias Afwerki, has led Eritrea since 1993. The People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) is the only legal political party.

In July 1996, the Constitution of Eritrea was approved, but it has not yet been fully put into practice.

In 1998, a border dispute with Ethiopia over the town of Badme led to the Eritrean-Ethiopian War. Thousands of soldiers from both countries died. Eritrea faced big economic and social problems, including many people being displaced and a severe problem with land mines.

The border war ended in 2000 with the signing of the Algiers Agreement. This agreement included setting up a UN peacekeeping mission (UNMEE) with over 4,000 peacekeepers. The UN created a 25-kilometer demilitarized zone inside Eritrea along the disputed border. Ethiopia was supposed to withdraw its troops to positions held before May 1998. The agreement also called for an independent UN body, the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC), to mark the border. The EEBC ruled in April 2002 that Badme belonged to Eritrea. Ethiopia rejected this decision and has not withdrawn its military from the disputed areas. A "difficult" peace remains.

The UNMEE mission officially ended in July 2008 because of problems getting fuel.

Eritrea's diplomatic relations with Djibouti were briefly cut off during the border war with Ethiopia in 1998. This was due to Djibouti's close ties with Ethiopia during the war. Relations were restored in 2000 but are tense again due to a new border dispute. Similarly, Eritrea and Yemen had a border conflict between 1996 and 1998 over the Hanish Islands. This was resolved in 2000 by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague.

Eritrea has improved its health care and is working to meet its Millennium Development Goals for health, especially for children. Life expectancy at birth increased from 39.1 years in 1960 to 59.5 years in 2008. Rates of mothers and children dying dropped significantly, and health facilities expanded.

Vaccinations and child nutrition have improved through working with schools. The number of children vaccinated against measles almost doubled in seven years. The number of underweight children decreased by 12% from 1995 to 2002. The National Malaria Protection Unit reported that deaths from malaria dropped by 85% and cases by 92% between 1998 and 2006. However, malaria and tuberculosis are still common. The rate of HIV for ages 15 to 49 years is over 2%.

Due to frustration with the stalled peace process with Ethiopia, President Isaias Afewerki wrote a series of letters to the UN Security Council and Secretary-General Kofi Annan. Tense relations with Ethiopia have continued, causing regional instability. Eritrea has also been accused of supporting certain groups in Somalia. The United States has considered labeling Eritrea a "State Sponsor of Terrorism."

In December 2007, about 4,000 Eritrean troops remained in the 'demilitarized zone', with 120,000 more along its side of the border. Ethiopia kept 100,000 troops on its side.

In September 2012, the Israeli newspaper Haaretz reported that there are over 40,000 Eritrean refugees in Israel. The organization Reporters Without Borders has ranked Eritrea last in freedom of expression since 2007.

The 2013 Eritrean Army mutiny happened on January 21, 2013. About 100-200 soldiers in Asmara briefly took over the state broadcaster, EriTV. They broadcast a message demanding reforms and the release of political prisoners. On February 10, 2013, President Isaias Afwerki said the mutiny was nothing to worry about.

In September 2018, President Isaias Afwerki and Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, signed a historic peace agreement between the two countries.

Asmara UNESCO World Heritage Site

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Asmera: a Modernist City of Africa |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Inscription | 2017 (41st Session) |

| Area | 481 ha |

| Buffer zone | 1,203 ha |

On July 8, 2017, the entire capital city of Asmara was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The city has thousands of Art Deco, futurist, modernist, and rationalist buildings. These were built during the period of Italian Eritrea. The city, nicknamed "La piccola Roma" ("Little Rome"), is located over 2000 meters above sea level.

Relations with neighbours

The BBC reported on June 19, 2008, about Eritrea's ongoing conflict with Ethiopia:

- 2007 September – A UN envoy warned that war could restart between Ethiopia and Eritrea over their border.

- 2007 November – Eritrea accepted the border line set by an international commission, but Ethiopia rejected it.

- 2008 January – The UN extended the mission for peacekeepers on the border for six months. The UN Security Council demanded Eritrea lift fuel restrictions on peacekeepers. Eritrea refused, saying troops must leave.

- 2008 February – The UN began pulling out its 1,700 peacekeepers due to lack of fuel after Eritrean government restrictions.

- 2008 April – UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon warned of a likely new war if peacekeepers fully withdrew.

- 2008 May – Eritrea asked the UN to end the peacekeeping mission.

Regarding the Djiboutian–Eritrean border conflict:

- 2008 April — Djibouti accused Eritrean troops of digging trenches and entering Djiboutian land. Eritrea denied this.

- 2008 June – Fighting broke out between Eritrean and Djiboutian troops.

- 2009, December 23 — The UN Security Council placed sanctions on Eritrea. This was for supporting armed groups in Somalia and for not withdrawing its forces after clashes with Djibouti in June 2008. The sanctions included an arms embargo, travel restrictions, and freezing assets of leaders. These sanctions were strengthened on December 5, 2011.

- 2010 June — Djibouti and Eritrea agreed to let Qatar mediate their dispute.

- 2017 June — After a diplomatic crisis in Qatar, Qatar withdrew its peacekeepers. Soon after, Djibouti accused Eritrea of reoccupying the disputed land.

Regarding southern Somalia: In December 2009, the United Nations Security Council placed sanctions on Eritrea. They accused Eritrea of arming and funding militia groups in Somalia's conflict zones. On July 16, 2012, a UN Monitoring Group reported that it found no evidence of direct Eritrean support for militia groups in the past year.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Eritrea para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Eritrea para niños

- Asmara

- History of Asmara

- History of Africa

- Italian Eritrea

- Timeline of Asmara

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |