History of Myanmar facts for kids

The history of Myanmar, also known as Burma, goes back about 13,000 years to its first human settlements. The earliest known people were the Pyu, who spoke a Tibeto-Burman language. They built city-states and adopted a religion called Theravada Buddhism.

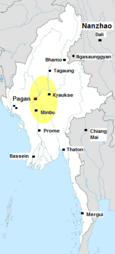

Later, in the early 800s, another group called the Bamar people arrived in the upper Irrawaddy valley. They created the Pagan Kingdom (1044–1297), which was the first time the Irrawaddy valley and its surrounding areas were united. During this time, the Burmese language and culture slowly became more common than the Pyu ways.

After the Mongols invaded in 1287, Myanmar broke into several smaller kingdoms. The main ones were the Kingdom of Ava, the Hanthawaddy Kingdom, the Kingdom of Mrauk U, and the Shan States. These kingdoms often formed alliances and fought wars.

In the late 1500s, the Toungoo dynasty (1510–1752) brought the country back together. For a short time, they built the largest empire in Southeast Asia. Later Toungoo kings made important changes to how the country was run and its economy. This led to a smaller, more peaceful, and richer kingdom in the 1600s and early 1700s.

In the late 1700s, the Konbaung dynasty (1752–1885) brought the kingdom back to power. They continued the Toungoo reforms, which increased central control over distant regions. This made Myanmar one of the most educated countries in Asia. The Konbaung dynasty also fought wars with all its neighbors. Eventually, the Anglo-Burmese wars (1824–85) led to British colonial rule.

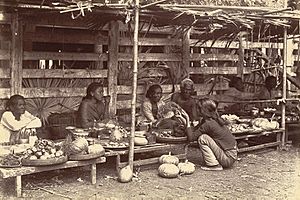

British rule brought many lasting changes to Myanmar's society, economy, culture, and government. It completely changed the country, which used to be mainly farming-based. British rule also made differences between the many ethnic groups in the country more noticeable.

Since gaining independence in 1948, Myanmar has been in one of the longest civil wars in the world. This war involves groups fighting for political and ethnic minority rights against different central governments. The country was under military rule in various forms from 1962 to 2010, and again from 2021 to the present. This cycle has made Myanmar one of the least developed nations in the world.

Contents

Early History (Before the 9th Century)

Ancient Times

Archaeological findings show that people lived in Burma as early as 11,000 BCE. Most signs of early settlements are in the central dry zone, close to the Irrawaddy River. The Stone Age in Burma, called the Anyathian, happened around the same time as the Paleolithic period in Europe.

Evidence of the New Stone Age, when people started farming and using polished stone tools, comes from three caves near Taunggyi. These caves date back to 10,000 to 6,000 BC.

Around 1500 BCE, people in the region learned to turn copper into bronze. They also started growing rice and raising chickens and pigs. They were among the first people in the world to do this. By 500 BCE, settlements that worked with iron appeared south of modern-day Mandalay. Archaeologists have found bronze-decorated coffins and burial sites with pottery. Evidence from the Samon Valley suggests that rice-growing communities traded with China between 500 BC and 200 CE. During the Iron Age, burial practices in the Samon Valley were influenced by India. For example, infants were buried in jars, and the size of the jar showed their family's status.

Pyu City-States

| Pyu City-States |

|---|

|

The Pyu people arrived in the Irrawaddy valley from what is now Yunnan around the 2nd century BCE. They then founded city-states throughout the valley. The Pyu were the first people in Burma about whom we have written records. During this time, Burma was part of a trade route that went from China to India. Trade with India brought Buddhism to the region. By the 4th century, many people in the Irrawaddy valley had become Buddhists.

The largest and most important Pyu city-state was the Sri Ksetra Kingdom, southeast of modern Pyay. In March 638, the Pyu of Sri Ksetra started a new calendar, which later became the Burmese calendar.

Chinese records from the 8th century mention 18 Pyu states. They described the Pyu as kind and peaceful people who rarely went to war. They wore cotton instead of silk so they wouldn't have to kill silkworms. The Chinese also noted that the Pyu knew how to calculate astronomical events. Many Pyu boys joined monasteries between the ages of seven and twenty.

The Pyu civilization lasted for almost a thousand years, until the early 9th century. Then, a new group of "swift horsemen" from the north, the Bamars, entered the upper Irrawaddy valley. In the early 800s, Pyu city-states in Upper Burma were constantly attacked by Nanzhao (in modern Yunnan). In 832, Nanzhao attacked Halingyi, which was the main Pyu city-state. Archaeologists believe that 3,000 Pyu prisoners were taken and became slaves in Kunming.

Pyu settlements remained in Upper Burma until the Pagan Empire began in the mid-11th century. Over the next four centuries, the Pyu slowly became part of the growing Burman kingdom of Pagan. The Pyu language was still spoken until the late 12th century. By the 13th century, the Pyu people had largely become Bamar. Their stories and legends were also included in the Bamar history.

Mon Kingdoms

Some historians from the colonial era believed that another group, the Mon people, started entering Lower Burma as early as the 6th century. They supposedly came from Mon kingdoms in modern-day Thailand. By the mid-9th century, these historians thought the Mon had founded at least two small kingdoms around Bago and Thaton. The first outside mention of a Mon kingdom in Lower Burma was by Arab geographers in 844–848.

However, recent studies show there is no archaeological evidence to support these ideas. It seems a Mon-speaking kingdom didn't exist in Lower Burma until the late 13th century. The first written claim that the kingdom of Thaton existed only appeared in 1479.

Bagan Dynasty (849–1297)

Early Bagan

The Burmans, who arrived during the Nanzhao raids on Pyu states in the early 9th century, settled in Upper Burma. Some Burman migrations into the upper Irrawaddy valley might have started even earlier, in the 7th century. In the mid-to-late 9th century, Pagan was founded as a fortified settlement. It was in a key location on the Irrawaddy River, near where it meets its main tributary, the Chindwin River.

Pagan might have been built to help Nanzhao control the surrounding countryside. Over the next two hundred years, this small area slowly grew. By the time Anawrahta became king in 1044, it covered about 200 miles from north to south and 80 miles from east to west.

Pagan Empire (1044–1297)

Over the next 30 years, Anawrahta founded the Pagan Kingdom. This was the first time the regions that would become modern-day Burma were united. By the late 12th century, Anawrahta's successors had expanded their influence. They reached south into the upper Malay Peninsula, east to the Salween River, north beyond the current China border, and west to northern Arakan and the Chin Hills.

By the early 12th century, Pagan had become a major power in Southeast Asia, alongside the Khmer Empire. Both China and India recognized Pagan's importance. By the mid-13th century, most of mainland Southeast Asia was controlled to some extent by either the Pagan Empire or the Khmer Empire.

Anawrahta also made important social, religious, and economic changes that had a lasting impact on Burmese history. His social and religious reforms later led to the modern-day culture of Myanmar. The most important change was bringing Theravada Buddhism to Upper Burma after Pagan conquered the Thaton Kingdom in 1057. With royal support, this Buddhist school slowly spread to villages over the next three centuries. However, other forms of Buddhism, Hinduism, and animism remained strong at all levels of society.

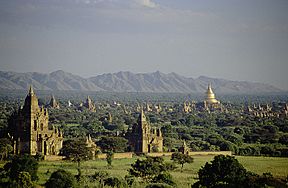

Pagan's economy mainly relied on farming in the Kyaukse and Minbu areas, where the Bamars built many new dams and canals. The kingdom also benefited from trade through its coastal ports. The kingdom's wealth was used to build over 10,000 Buddhist temples in the Pagan capital area between the 11th and 13th centuries. About 3,000 of these temples still stand today. Wealthy people donated tax-free land to religious authorities.

The Burmese language and culture slowly became dominant in the upper Irrawaddy valley. They replaced Pyu and Pali customs by the late 12th century. By then, the Bamar leaders of the kingdom were clearly in charge. The Pyu people in Upper Burma had largely adopted the Bamar ethnicity. The Burmese language, which was once foreign, became the common language of the kingdom.

The kingdom began to decline in the 13th century. The continuous growth of tax-free religious wealth meant that by the 1280s, two-thirds of Upper Burma's farmland belonged to religious groups. This made it harder for the king to keep the loyalty of his officials and soldiers. This led to internal problems and challenges from the Mons, Mongols, and Shans.

Starting in the early 13th century, the Shan people began to surround the Pagan Empire from the north and east. The Mongols, who had conquered Yunnan (the former homeland of the Bamar) in 1253, invaded Pagan in 1277. They attacked in response to a diplomatic issue. In 1287, the Mongols sacked Pagan, ending the Pagan Kingdom's 250-year rule. The Pagan king abandoned his palace when he heard the Mongols were coming. Pagan's rule over central Burma ended ten years later in 1297 when it was overthrown by the Myinsaing Kingdom, led by Shan rulers.

Small Kingdoms

After Pagan fell, the Mongols left the hot Irrawaddy valley. But the Pagan Kingdom was completely broken into several small kingdoms. By the mid-14th century, the country was divided into four main power centers: Upper Burma, Lower Burma, the Shan States, and Arakan. Many of these centers were themselves made up of smaller, often loosely connected, kingdoms or states. This period was full of wars and changing alliances. Smaller kingdoms often had to pledge loyalty to more powerful states, sometimes even to several at once.

Ava (1364–1555)

The Kingdom of Ava (Inwa) was founded in 1364. It followed earlier, smaller kingdoms in central Burma. In its early years, Ava saw itself as the rightful heir to the Pagan Kingdom and tried to rebuild the old empire. At its strongest, it managed to bring the Taungoo-ruled kingdom and some Shan states under its control. However, it failed to reconquer the rest of the former empire.

The Forty Years' War (1385–1424) with Hanthawaddy left Ava exhausted, and its power stopped growing. Its kings often faced rebellions in their vassal regions but managed to put them down until the 1480s. In the late 15th century, the Prome Kingdom and its Shan States successfully broke away. In the early 16th century, Ava itself was attacked by its former vassals. In 1510, Taungoo also became independent. In 1527, the Confederation of Shan States, led by Mohnyin, captured Ava. The Confederation ruled Upper Burma until 1555, but its rule was marked by internal fighting. Taungoo forces finally overthrew the kingdom in 1555.

The Burmese language and culture truly developed between the last period of the Pagan Kingdom and the Ava period.

Hanthawaddy Pegu (1287–1539, 1550–52)

The Mon-speaking kingdom of Hanthawaddy was founded right after Pagan's collapse in 1297. At first, this kingdom in Lower Burma was a loose group of regional power centers. The strong rule of King Razadarit (1384–1421) made the kingdom stable. Razadarit firmly united the three Mon-speaking regions and successfully defended against Ava in the Forty Years' War (1385–1424).

After the war, Hanthawaddy entered its golden age, while its rival Ava slowly declined. From the 1420s to the 1530s, Hanthawaddy was the most powerful and prosperous of all the kingdoms after Pagan. Under a series of very skilled kings, the kingdom enjoyed a long period of wealth, benefiting from foreign trade. The kingdom, with its thriving Mon language and culture, became a center for trade and Theravada Buddhism.

Because its last ruler was inexperienced, the powerful kingdom was conquered by the rising Taungoo dynasty in 1539. The kingdom briefly came back to life between 1550 and 1552, but it only controlled Pegu and was crushed by Taungoo in 1552.

Shan States (1287–1563)

The Shan people, who are ethnic Tai people, came with the Mongols and stayed. They quickly came to control much of the northern and eastern parts of Burma. This area stretched from northwestern Sagaing Division to the Kachin Hills and the present-day Shan Hills.

The most powerful Shan states were Mohnyin and Mogaung. Other important states included Hsenwi, Hsipaw, and Momeik.

Mohnyin, in particular, constantly raided Ava's territory in the early 16th century. The Mohnyin-led Confederation of Shan States, allied with the Prome Kingdom, captured Ava itself in 1527. The Confederation defeated its former ally Prome in 1532. It then ruled all of Upper Burma except Taungoo. But the Confederation was weakened by internal disagreements and could not stop Taungoo, which conquered Ava in 1555 and all of the Shan States by 1563.

Arakan (1287–1785)

Arakan had been independent since the late Pagan period, but its early rulers were not very effective. Until the Mrauk-U Kingdom was founded in 1429, Arakan was often caught between larger neighbors. It became a battlefield during the Forty Years' War between Ava and Pegu. Mrauk-U grew into a powerful kingdom between the 15th and 17th centuries, even controlling East Bengal from 1459 to 1666. Arakan was the only kingdom after Pagan that was not taken over by the Toungoo dynasty.

Toungoo Dynasty (1510–1752)

First Toungoo Empire (1510–99)

| First Taungoo Empire |

|---|

|

Starting in the 1480s, Ava faced constant internal rebellions and attacks from the Shan States, and it began to fall apart. In 1510, Taungoo, located in a remote southeastern part of the Ava kingdom, also declared independence. When the Confederation of Shan States conquered Ava in 1527, many people fled to Taungoo, which was the only peaceful kingdom.

Taungoo, led by its ambitious king Tabinshwehti and his general Bayinnaung, went on to reunite the small kingdoms that had existed since the fall of the Pagan Empire. They created the largest empire in Southeast Asian history. First, the rising kingdom defeated a more powerful Hanthawaddy in the Taungoo–Hanthawaddy War (1534–41). Tabinshwehti moved the capital to the newly captured city of Bago in 1539.

Taungoo had expanded its power up to Pagan by 1544. Tabinshwehti's successor, Bayinnaung, continued to expand the empire. He conquered Ava in 1555, the Shan States (1557–1563), Lan Na (1558), Manipur (1560), Siam (1564, 1569), and Lan Xang (1565–74). This brought much of western and central mainland Southeast Asia under his rule.

Bayinnaung set up a lasting system that reduced the power of hereditary Shan chiefs and made Shan customs more like those of the lowlands. However, he couldn't create an effective system everywhere in his vast empire. His empire was a loose collection of former independent kingdoms. Their kings were loyal to him as the "Universal Ruler," not to the kingdom of Taungoo itself.

The empire, which had spread too far, began to fall apart soon after Bayinnaung's death in 1581. Siam broke away in 1584 and fought Burma until 1605. By 1597, the kingdom had lost all its lands, including Taungoo, the dynasty's original home. In 1599, Arakanese forces, helped by Portuguese soldiers, and allied with rebellious Taungoo forces, attacked Pegu. The country fell into chaos, with each region claiming its own king. A Portuguese soldier named Filipe de Brito e Nicote rebelled against his Arakanese masters and established Portuguese rule at Thanlyin in 1603.

Even though it was a difficult time for Myanmar, the Toungoo expansions increased the nation's international reach. Rich merchants from Myanmar traded as far as the Philippines, selling Burmese sugar for gold. Filipinos also had merchant communities in Myanmar. Filipino soldiers were hired as mercenaries for both Siam (Thailand) and Burma (Myanmar) in the Burmese-Siamese Wars, just like the Portuguese.

Restored Taungoo Kingdom (Nyaungyan Restoration) (1599–1752)

The period of chaos after the fall of the First Toungoo Empire was much shorter than the one after the Pagan Empire fell. One of Bayinnaung's sons, Nyaungyan Min, immediately began to reunite the country. He successfully restored central authority over Upper Burma and nearby Shan states by 1606.

His successor, Anaukpetlun, defeated the Portuguese at Thanlyin in 1613. He took back the upper Tanintharyi coast to Dawei and Lan Na from the Siamese by 1614. He also captured the Shan states across the Salween River (Kengtung and Sipsongpanna) between 1622 and 1626.

His brother, Thalun, rebuilt the war-torn country. He ordered the first census in Burmese history in 1635, which showed that the kingdom had about two million people. By 1650, these three capable kings—Nyaungyan, Anaukpetlun, and Thalun—had successfully rebuilt a smaller but much more manageable kingdom.

More importantly, the new dynasty created a legal and political system that would last until the 19th century under the Konbaung dynasty. The king completely replaced hereditary chiefs with appointed governors throughout the Irrawaddy valley. They also greatly reduced the hereditary rights of Shan chiefs. The dynasty also controlled the growing wealth and independence of monasteries, which gave the government more tax money. Its trade and government reforms created a prosperous economy for over 80 years. Except for a few rebellions and one external war (Burma defeated Siam's attempt to take Lan Na and Mottama in 1662–64), the kingdom was mostly peaceful for the rest of the 17th century.

The kingdom slowly declined, and the power of the "palace kings" weakened quickly in the 1720s. From 1724 onwards, the Meitei people began raiding the upper Chindwin River. In 1727, southern Lan Na successfully rebelled, leaving only northern Lan Na under a weakening Burmese rule. Meitei raids became more frequent in the 1730s, reaching deeper into central Burma.

In 1740, the Mon people in Lower Burma started a rebellion. They founded the Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom and by 1745 controlled much of Lower Burma. The Siamese also extended their power up the Tanintharyi coast by 1752. Hanthawaddy invaded Upper Burma in November 1751 and captured Ava on March 23, 1752, ending the 266-year-old Toungoo dynasty.

Konbaung Dynasty (1752–1885)

Reunification

| Konbaung Dynasty |

|---|

|

Soon after Ava fell, a new dynasty rose in Shwebo to challenge Hanthawaddy's power. Over the next 70 years, the very militaristic Konbaung dynasty created the largest Burmese empire, second only to Bayinnaung's empire. By 1759, King Alaungpaya's Konbaung forces had reunited all of Burma (and Manipur). They completely ended the Mon-led Hanthawaddy dynasty and drove out the European powers who had supplied weapons to Hanthawaddy—the French from Thanlyin and the English from Cape Negrais.

Wars with Siam and China

The kingdom then went to war with the Ayutthaya Kingdom (Siam). Siam had taken control of the Tanintharyi coast up to Mottama during the Burmese civil war (1740–1757) and had given shelter to Mon refugees. By 1767, the Konbaung armies had conquered much of Laos and defeated Siam. But they couldn't completely defeat the remaining Siamese resistance because they had to defend against four invasions by Qing China (1765–1769). The Burmese defenses held strong, but the Burmese were busy defending against another possible invasion from China for years. The Qing kept a large military force on the border for about ten years, trying to start another war, and banned trade for two decades.

The Ayutthaya Kingdom used Burma's focus on China to take back their lost territories by 1770. They also captured much of Lan Na by 1775, ending over two centuries of Burmese control over that region. They fought wars again several times between 1775 and 1855, but these wars usually ended in a stalemate. After decades of fighting, the two countries essentially traded Tanintharyi (to Burma) and Lan Na (to Siam).

Westward Expansion and Wars with British Empire

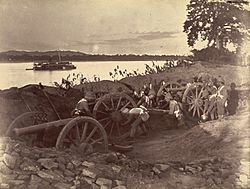

Facing a powerful China in the northeast and a strong Siam in the southeast, King Bodawpaya looked westward for expansion. He conquered Arakan in 1785, took over Manipur in 1814, and captured Assam in 1817–1819. This created a long, unclear border with British India. Bodawpaya's successor, King Bagyidaw, had to deal with British-supported rebellions in Manipur in 1819 and Assam in 1821–1822. Raids by rebels from British-controlled areas and counter-raids by the Burmese led to the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–26).

This war lasted two years and cost 13 million pounds. It was the longest and most expensive war in British Indian history, but it ended in a clear British victory. Burma had to give up all the western lands Bodawpaya had gained (Arakan, Manipur, and Assam) plus Tenasserim. Burma was severely weakened for years by having to pay a large payment of one million pounds. In 1852, the British easily took the Pegu province in the Second Anglo-Burmese War.

After the war, King Mindon Min tried to modernize the Burmese state and economy. He made trade and land deals to prevent further British takeovers, including giving the Karenni States to the British in 1875. However, the British, worried about French expansion in Indochina, annexed the rest of the country in the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885. They sent the last Burmese king, Thibaw Min, and his family into exile in India.

Government and Money Changes

Konbaung kings continued the government changes started in the Restored Toungoo Dynasty period (1599–1752). They achieved new levels of control within the country and expanded its borders. Konbaung kings tightened control in the lowlands and reduced the inherited powers of Shan chiefs. Konbaung officials, especially after 1780, began economic changes that increased government income and made it more predictable. A money-based economy continued to grow. In 1857, the king started a full system of cash taxes and salaries, helped by the country's first standardized silver coins.

Culture

Cultural blending continued. For the first time in history, the Burmese language and culture became dominant throughout the entire Irrawaddy valley. The Mon language and ethnicity were almost completely replaced by 1830. The nearby Shan states adopted more lowland customs. Burmese literature and theater continued to grow, helped by a very high literacy rate for adult men at the time (half of all men and 5% of women could read). Monastic and educated elites around the Konbaung kings, especially from Bodawpaya's reign, also started a major reform of Burmese intellectual life and monastic practices. This led to, among other things, Burma's first proper state histories.

British Rule

Britain made Burma a province of India in 1886, with Rangoon as its capital. Traditional Burmese society changed greatly because the monarchy ended and religion was separated from the state. Although the official war ended quickly, resistance continued in northern Burma until 1890. The British eventually destroyed villages and appointed new officials to stop all guerrilla activity.

The economy also changed a lot. After the Suez Canal opened, the demand for Burmese rice grew. Huge areas of land were opened for farming. However, to prepare new land, farmers had to borrow money from Indian moneylenders called chettiars at high interest rates. They often lost their land and animals because they couldn't repay the loans. Most jobs also went to Indian laborers. Whole villages became outlaws as people resorted to armed robbery. While the Burmese economy grew, most of the power and wealth stayed with British companies, Anglo-Burmese people, and migrants from India. The civil service was mostly staffed by Anglo-Burmese and Indians, and Bamars were largely kept out of military service.

Around the start of the 20th century, a nationalist movement began. It started as the Young Men's Buddhist Association (YMBA), similar to the YMCA, because religious groups were allowed by the British. Later, the General Council of Burmese Associations (GCBA) took over. This group was linked to "National Associations" that appeared in villages across Burma. Between 1900 and 1911, a Buddhist monk named U Dhammaloka challenged Christianity and British rule based on religion.

A new generation of Burmese leaders emerged in the early 1900s from educated classes who were allowed to study law in London. They came back believing that Burma's situation could improve through reforms. Changes in the early 1920s led to a legislature with limited powers, a university, and more self-rule for Burma within India's administration. Efforts were also made to increase Burmese representation in the civil service. However, some people felt that changes were too slow and not enough.

In 1920, the first university student strike in history happened. Students protested a new University Act they believed would only help the rich and continue colonial rule. "National Schools" opened across the country to protest the colonial education system. This strike is now remembered as "National Day." There were more strikes and anti-tax protests in the late 1920s led by the National Associations. Buddhist monks were important activists, such as U Ottama and U Seinda, who later led armed rebellions. U Wisara was the first martyr of the movement, dying after a long hunger strike in prison.

In December 1930, a local tax protest by Saya San quickly grew into a regional and then a national rebellion against the government. This "Galon Rebellion" lasted two years and needed thousands of British troops to stop it. The British also promised more political reforms. Saya San was eventually tried and executed. His defense helped several future national leaders, including Ba Maw and U Saw, become well-known.

In May 1930, the "We Bamars Association" (Dobama Asiayone) was founded. Its members called themselves Thakin, which means "master" in Burmese. This was an ironic name, as it declared that they were the true masters of the country, not the colonial rulers. The second university student strike in 1936 happened because Aung San and Ko Nu, leaders of the Rangoon University Students Union, were expelled. They refused to name the author of an article that criticized a university official. The strike spread to Mandalay, leading to the formation of the All Burma Students Union. Aung San and Nu later joined the Thakin movement, moving from student politics to national politics.

The British separated Burma from India in 1937 and gave the colony a new constitution with a fully elected assembly. However, this caused disagreements. Some Burmese felt it was a trick to keep them out of Indian reforms, while others saw any move away from Indian control as positive. Ba Maw was the first prime minister of Burma. He was followed by U Saw in 1939, who served until he was arrested in January 1942 for talking with the Japanese.

A wave of strikes and protests started in the oilfields of central Burma in 1938. This became a general strike with major consequences. In Rangoon, student protesters were charged by mounted police, and a student named Aung Kyaw was killed. In Mandalay, colonial police shot into a crowd led by Buddhist monks, killing 17 people. This movement became known as the "1300 Revolution." December 20, the day Aung Kyaw died, is remembered by students as "Bo Aung Kyaw Day."

World War II

Some Burmese nationalists saw World War II as a chance to get concessions from the British in exchange for supporting the war. Other Burmese, like the Thakin movement, were against Burma joining the war under any circumstances. Aung San co-founded the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in August 1939. Writings about Marxism and the Sinn Féin movement in Ireland were widely read among political activists. Aung San also helped found the People's Revolutionary Party (PRP), which was renamed the Socialist Party after World War II. He also helped create the Freedom Bloc, an alliance of different groups.

After the Dobama organization called for a national uprising, an arrest warrant was issued for many leaders, including Aung San, who escaped to China. Aung San wanted to contact Chinese Communists, but he was found by Japanese authorities. They offered him support by forming a secret intelligence unit called the Minami Kikan. Its goal was to close the Burma Road and support a national uprising. Aung San briefly returned to Burma to recruit 29 young men who went to Japan with him for military training. They became known as the "Thirty Comrades". When the Japanese occupied Bangkok in December 1941, Aung San announced the formation of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) in anticipation of the Japanese invasion of Burma in 1942.

The BIA formed a temporary government in some areas of the country in the spring of 1942. However, there were disagreements among Japanese leaders about Burma's future. While Colonel Suzuki encouraged the Thirty Comrades to form a government, the Japanese Military leadership never formally accepted such a plan. Eventually, the Japanese Army chose Ba Maw to form a government. During the war in 1942, the BIA grew uncontrollably. In many districts, officials and even criminals appointed themselves to the BIA. It was reorganized as the Burma Defence Army (BDA) under the Japanese, but still led by Aung San. The BIA had been an irregular force, but the BDA was recruited by selection and trained as a regular army by Japanese instructors. Ba Maw was declared head of state. His cabinet included Aung San as War Minister and the Communist leader Thakin Than Tun as Minister of Land and Agriculture. When the Japanese declared Burma theoretically independent in 1943, the Burma Defence Army (BDA) was renamed the Burma National Army (BNA).

Joining the Allies

It soon became clear that Japanese promises of independence were just a trick, and that Ba Maw had been deceived. As the war turned against the Japanese, they declared Burma a fully sovereign state on August 1, 1943, but this was another false front. Disappointed, Aung San began talks with Communist leaders Thakin Than Tun and Thakin Soe, and Socialist leaders Ba Swe and Kyaw Nyein. This led to the formation of the Anti-Fascist Organisation (AFO) in August 1944. The AFO was later renamed the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL).

There were informal contacts between the AFO and the Allies in 1944 and 1945. On March 27, 1945, the Burma National Army rose up in a countrywide rebellion against the Japanese. March 27 had been celebrated as "Resistance Day" until the military renamed it "Tatmadaw (Armed Forces) Day." Aung San and others then began talks with Lord Mountbatten and officially joined the Allies as the Patriotic Burmese Forces (PBF). The Japanese were driven out of most of Burma by May 1945. Negotiations then began with the British about disarming the AFO and its troops joining a post-war Burma Army. Some veterans formed a paramilitary force under Aung San, called the People's Volunteer Organisation (PVO). The PBF was successfully integrated into the new army at the Kandy conference in Ceylon in September 1945.

Under Japanese occupation, between 170,000 and 250,000 civilians died.

After World War II

When the Japanese surrendered, a military government was set up in Burma. There were demands to try Aung San for his involvement in a murder during military operations in 1942. Lord Mountbatten realized this was impossible given Aung San's popularity.

After the war, the British Governor, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, returned. The restored government focused on rebuilding the country and delayed talks about independence. The AFPFL opposed the government, leading to political instability. A disagreement also grew within the AFPFL between the Communists and Aung San with the Socialists over strategy. This led to Than Tun being forced to resign in July 1946 and the CPB being expelled from the AFPFL in October.

Sir Hubert Rance replaced Dorman-Smith as the new governor. Almost immediately, the Rangoon Police went on strike. The strike, starting in September 1946, spread to government employees and almost became a general strike. Rance calmed the situation by meeting with Aung San and convincing him to join the Governor's Executive Council with other AFPFL members. The new council, which now had more trust in the country, began talks for Burmese independence. These talks successfully concluded in London with the Aung San-Attlee Agreement on January 27, 1947. However, parts of the communist and conservative branches of the AFPFL were unhappy.

Aung San also successfully reached an agreement with ethnic minorities for a unified Burma at the Panglong Conference on February 12. This day is now celebrated as "Union Day." The popularity of the AFPFL, now led by Aung San and the Socialists, was confirmed when it won a huge victory in the April 1947 elections. On July 19, 1947, U Saw, a former prime minister, arranged the assassination of Aung San and several members of his cabinet. July 19 has since been remembered as "Martyrs' Day." Soon after, a rebellion led by the monk U Seinda broke out in Arakan and began to spread.

Thakin Nu, the Socialist leader, was then asked to form a new cabinet. He oversaw Burmese independence, which was established on January 4, 1948. The desire to separate from the British was so strong that Burma chose not to join the Commonwealth of Nations, unlike India or Pakistan.

Independent Burma

1948–62

The first years of independent Burma were marked by several rebellions. These included the Red Flag Communists, the White Flag Communists, the People's Volunteer Organisation, army rebels, Arakanese Muslims, and the Karen National Union.

After the Communist victory in China in 1949, remote areas of Northern Burma were controlled for many years by a Kuomintang (KMT) army. Burma accepted foreign help to rebuild in these early years. However, continued American support for the Chinese Nationalist military in Burma eventually led the country to reject most foreign aid. Burma refused to join the South-East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and supported the Bandung Conference of 1955. Burma generally tried to be neutral in world affairs. It was one of the first countries to recognize Israel and the People's Republic of China.

By 1958, the country's economy was starting to recover. However, it began to fall apart politically due to a split in the AFPFL into two groups. The situation in parliament became very unstable. U Nu survived a no-confidence vote only with the support of the opposition. Army leaders saw a "threat" of the Communist Party reaching an agreement with U Nu. In the end, U Nu "invited" Army Chief of Staff General Ne Win to take over the country. Over 400 "communist sympathizers" were arrested, and 153 were sent to Coco Island. Newspapers were also closed down.

Ne Win's temporary government successfully stabilized the situation and prepared for new general elections in 1960. U Nu's Union Party won with a large majority. However, the situation did not stay stable for long. The Shan Federal Movement, which wanted a "loose" federation, was seen as a separatist movement. It insisted on the government honoring the right to leave the union after 10 years, as allowed by the 1947 Constitution. Ne Win had already succeeded in taking away the feudal powers of the Shan Sawbwas (chiefs) in exchange for comfortable lifetime pensions in 1959.

1962–88

On March 2, 1962, Ne Win, with sixteen other senior military officers, staged a coup d'état. They arrested U Nu and others, and declared a socialist state to be run by their "Union Revolutionary Council." Sao Shwe Thaik's son was shot dead in what was generally called a "bloodless" coup. Another Shan chief also mysteriously disappeared after being stopped at a checkpoint.

A number of protests followed the coup. Initially, the military's response was mild. However, on July 7, 1962, a peaceful student protest on Rangoon University campus was stopped by the military. The next day, the army blew up the Students Union building. Peace talks were held with various armed rebel groups in 1963, but without any breakthrough. During and after the talks, hundreds of people were arrested. All opposition parties were banned on March 28, 1964. The Kachin insurgency had begun earlier in 1961 after U Nu declared Buddhism the state religion. The Shan State Army launched a rebellion in 1964 because of the 1962 military coup.

Ne Win quickly moved to turn Burma into his vision of a "socialist state" and to isolate the country from the rest of the world. A one-party system was established, with his newly formed Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP) in complete control. Businesses and industries were taken over by the state. However, the economy did not grow at first because the government focused too much on industrial development instead of agriculture. In April 1972, General Ne Win and the rest of the Union Revolutionary Council retired from the military, but Ne Win continued to run the country through the BSPP. A new constitution was created in January 1974, which led to the creation of a People's Assembly that held all government power. Ne Win became the president of the new government.

Starting in May 1974, strikes hit Rangoon and other parts of the country due to corruption, rising prices, and food shortages, especially rice. In Rangoon, workers were arrested, and troops fired on workers at a textile mill and dockyard. In December 1974, the biggest anti-government demonstrations happened over the funeral of former UN Secretary-General U Thant. U Thant was seen as a symbol of opposition to the military government. Burmese people felt that U Thant was denied a state funeral he deserved because of his connection to U Nu.

On March 23, 1976, over 100 students were arrested for holding a peaceful ceremony to mark 100 years since the birth of Thakin Kodaw Hmaing. He was a great Burmese poet, writer, and nationalist leader. He inspired many Burmese nationalists and writers, making them proud of their history and culture. He encouraged direct action like student and worker strikes. Hmaing, as leader of the Dobama Organization, sent the Thirty Comrades abroad for military training, which led to the modern Myanmar Army. After independence, he worked for peace until he died in 1964.

In 1978, a military operation against the Rohingya Muslims in Arakan, called the King Dragon operation, caused 250,000 refugees to flee to Bangladesh.

U Nu, after being released from prison in October 1966, left Burma in April 1969. He formed the Parliamentary Democracy Party (PDP) in Bangkok, Thailand, with former Thirty Comrades. The PDP launched an armed rebellion from 1972 until 1978. U Nu and others returned to Rangoon after an amnesty in 1980. Ne Win also secretly held peace talks with rebel groups in 1980, but they ended without agreement.

Crisis and the 1988 Uprising

Ne Win retired as president in 1981, but he remained in power as Chairman of the BSPP until his sudden announcement to step down on July 23, 1988. In the 1980s, the economy began to grow as the government eased rules on foreign aid. But by the late 1980s, falling prices for goods and rising debt led to an economic crisis. This led to economic changes in 1987–1988 that relaxed socialist controls and encouraged foreign investment. However, this was not enough to stop growing unrest in the country. This was made worse by repeated "demonetization" of certain banknotes, the last of which happened in September 1987. This wiped out the savings of most people.

In September 1987, Burma's ruler, U Ne Win, suddenly canceled certain currency notes. This caused a big economic downturn. The main reason for canceling these notes was Ne Win's superstition; he considered the number nine his lucky number. He only allowed 45 and 90 kyat notes because they could be divided by nine. Burma being classified as a "Least Developed Country" by the UN the following December showed its economic failure.

In March and June 1988, brutal police actions against student-led protests caused the deaths of over a hundred students and civilians. This triggered widespread protests and demonstrations across the country on August 8. The military responded by firing into crowds, claiming Communist involvement. Chaos and disorder took over. The civil government stopped working, and by September, the country was close to a revolution. The armed forces, led by General Saw Maung, staged a coup on August 8 to restore order. During the 8888 Uprising, as it became known, the military killed thousands. The military replaced the 1974 Constitution with martial law under the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), with Saw Maung as chairman and prime minister.

At a press conference on August 5, 1989, Brig. Gen. Khin Nyunt, the SLORC Secretary 1, claimed that the uprising had been organized by the Communist Party of Burma. While there might have been some underground Communist presence, there was no evidence that they were in charge. In fact, in March 1989, the Communist Party leadership was overthrown by a rebellion by its own troops. The Communist leaders were soon forced into exile.

1990–2006

The military government announced a name change for the country in English from "Burma" to "Myanmar" in 1989. It also continued the economic reforms started by the old government. It called for a Constituent Assembly to change the 1974 Constitution. This led to multi-party elections in May 1990, where the National League for Democracy (NLD) won a huge victory.

However, the military would not let the assembly meet. They continued to keep the two NLD leaders, Tin Oo and Aung San Suu Kyi (daughter of Aung San), under house arrest. Burma faced increasing international pressure to allow the elected assembly to meet, especially after Aung San Suu Kyi won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. The country also faced economic sanctions. In April 1992, the military replaced Saw Maung with General Than Shwe.

Than Shwe released U Nu from prison and eased some restrictions on Aung San Suu Kyi's house arrest, finally releasing her in 1995. However, she was not allowed to leave Rangoon. Than Shwe also finally allowed a National Convention to meet in January 1993, but he insisted that the military keep a major role in any future government. The NLD, tired of the interference, walked out in late 1995. The assembly was finally dismissed in March 1996 without creating a constitution.

During the 1990s, the military government also had to deal with several rebellions by ethnic minorities along its borders. General Khin Nyunt was able to negotiate cease-fire agreements that ended fighting with some groups, but the Karen people would not negotiate. The military finally captured the main Karen base in spring 1995, but there has still been no final peace agreement.

After the National Convention failed to create a new constitution, tensions between the government and the NLD grew. This resulted in two major crackdowns on the NLD in 1996 and 1997. The SLORC was ended in November 1997 and replaced by the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), but this was mostly a cosmetic change. Continued reports of human rights violations in Burma led the United States to increase sanctions in 1997, and the European Union followed in 2000.

The military placed Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest again in September 2000 until May 2002, when her travel restrictions were also lifted. Talks were held with the government, but these reached a standstill. Suu Kyi was again taken into custody in May 2003 after an attack on her motorcade. The government also carried out another large crackdown on the NLD, arresting many leaders and closing most of its offices. The situation in Burma remains tense.

In August 2003, Kyin Nyunt announced a seven-step "roadmap to democracy." The government claimed it was implementing this plan. However, there was no timeline, conditions, or independent way to check if it was moving forward. For these reasons, most Western governments and Burma's neighbors were doubtful.

On February 17, 2005, the government restarted the National Convention, for the first time since 1993, to rewrite the Constitution. However, major pro-democracy groups, including the National League for Democracy, were not allowed to participate. The military only allowed selected smaller parties. It was stopped again in January 2006.

In November 2005, the military government started moving the capital away from Yangon to a new city near Pyinmana. This public action followed a long-term unofficial policy of moving important military and government buildings away from Yangon to avoid a repeat of the 1988 events. On Armed Forces Day (March 27, 2006), the capital was officially named Naypyidaw (meaning "Royal City of the Seat of Kings"). In 2005, the capital city was officially relocated from Yangon to Naypyidaw.

In November 2006, the International Labour Organization (ILO) announced it would seek to prosecute members of the ruling Myanmar government for "crimes against humanity" over the continuous forced labor of its citizens by the military. The ILO estimated that 800,000 people were subject to forced labor in Myanmar.

2007 Anti-Government Protests

The 2007 Burmese anti-government protests began on August 15, 2007. The immediate cause was the military government's sudden decision to remove fuel subsidies. This caused the price of diesel and petrol to double, and the price of natural gas for buses to increase five times in less than a week. At first, the protests were dealt with quickly and harshly by the government, with many protesters arrested. Starting September 18, thousands of Buddhist monks led the protests. These protests were allowed to continue until a new government crackdown on September 26.

During the crackdown, there were rumors of disagreements within the Burmese military, but these were not confirmed. At the time, independent sources reported that 30 to 40 monks and 50 to 70 civilians were killed, and 200 were beaten. Some news reports called the protests the Saffron Revolution.

On February 7, 2008, the SPDC announced that a vote for the Constitution would be held, and elections by 2010. The 2008 Burmese constitutional referendum was held on May 10 and promised a "discipline-flourishing democracy" for the country in the future.

Cyclone Nargis

On May 3, 2008, Cyclone Nargis hit the country. Winds of up to 215 km/h (135 mph) struck the densely populated, rice-farming delta of the Irrawaddy Division. It is estimated that more than 130,000 people died or went missing, and damage totaled 10 billion US dollars. It was the worst natural disaster in Burmese history. The World Food Programme reported that "Some villages have been almost totally eradicated and vast rice-growing areas are wiped out."

The United Nations estimated that as many as 1 million people were left homeless. The World Health Organization "received reports of malaria outbreaks in the worst-affected area." However, in the critical days after this disaster, Burma's isolated government made recovery efforts difficult. They delayed the entry of United Nations planes delivering medicine, food, and other supplies. The government's failure to allow large-scale international relief efforts was described by the United Nations as "unprecedented."

2011–2016

The 2011–2012 Burmese democratic reforms were a series of political, economic, and administrative changes made by the military-backed government. These reforms included releasing pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest and starting talks with her. They also established the National Human Rights Commission, granted general amnesties to over 200 political prisoners, and created new labor laws allowing unions and strikes. Press censorship was relaxed, and currency practices were regulated.

Because of these reforms, ASEAN approved Burma's request to chair the organization in 2014. United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited Burma on December 1, 2011, to encourage more progress. It was the first visit by a US Secretary of State in over fifty years. United States President Barack Obama visited one year later, becoming the first US president to visit the country.

Aung San Suu Kyi's party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), participated in by-elections held on April 1, 2012. The government had removed laws that led to the NLD boycotting the 2010 general election. She led the NLD to a landslide victory in the by-elections, winning 41 out of 44 contested seats. Suu Kyi herself won a seat in the lower house of the Burmese Parliament.

The 2015 election results gave the National League for Democracy a clear majority of seats in both houses of parliament. This was enough to ensure that their candidate would become president, even though NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi was not allowed to be president by the constitution. However, clashes between Burmese troops and local rebel groups continued.

2016–2021

The new parliament met on February 1, 2016. On March 15, 2016, Htin Kyaw was elected as the first non-military president of the country since the military coup of 1962. Aung San Suu Kyi took on the new role of the State Counsellor, a position similar to Prime Minister, on April 6, 2016.

The big victory of Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy in the 2015 general elections raised hopes for Myanmar to successfully change from military rule to a free democratic system. However, internal political problems, a struggling economy, and ethnic conflicts continued to make the move to democracy difficult. The 2017 murder of Ko Ni, a prominent Muslim lawyer and key member of Myanmar's ruling party, was seen as a serious blow to the country's fragile democracy. His death meant Aung San Suu Kyi lost an important advisor, especially on changing Myanmar's military-written Constitution and bringing the country to democracy.

There was a military crackdown against Rohingya people from October 2016 to January 2017, and another one started in August 2017. This crisis forced over a million Rohingya to flee to other countries. Most fled to Bangladesh, leading to the creation of the Kutupalong refugee camp, the world's largest refugee camp.

In the general election on November 8, 2020, the National League for Democracy (NLD) won 396 out of 476 seats in parliament. This was an even bigger victory than in the 2015 election. The military's party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, won only 33 seats.

2021–Present

On February 1, 2021, Myanmar's military, the Tatmadaw, arrested the state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and other government members. The military gave power to the military chief Min Aung Hlaing, and a state of emergency was declared for one year.

On February 2, 2021, healthcare workers and civil servants across the country, including in the capital, Naypyidaw, started a national civil disobedience movement. This was in opposition to the coup. Protesters used peaceful methods, including strikes, a military boycott, pot-banging, a red ribbon campaign, public protests, and formal recognition of the election results by elected representatives.

On February 20, two people were shot dead and at least two dozen more were injured in Mandalay by the military during a violent crackdown. These people were residents guarding government shipyard workers who were part of the civil disobedience movement. In addition to firing live rounds, the police and military also beat, arrested, used water cannons, and threw objects at civilians.

As of March 26, 2021, at least 3,070 people had been arrested, and at least 423 protesters had been killed by military or police forces.

Armed rebellions by the People's Defence Force of the National Unity Government have broken out across Myanmar. In many villages and towns, military attacks forced tens of thousands of people to flee. UNOCHA reported that as of early September 2022, 974,000 people had been displaced within the country since the coup. Also, between the February 2021 coup and June 2022, over 40,000 people fled to neighboring countries, including many from communities near the borders that came under attack.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Birmania para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Birmania para niños

- History of Asia

- List of Burmese monarchs

- Burmese monarchs' family tree

- List of presidents of Burma

- Politics of Burma

- Prime Minister of Burma

- Timeline of Burmese history