Pyu city-states facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pyu city-states

ပျူ မြို့ပြ နိုင်ငံများ

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2nd century BCE–c. 1050 | |||||||||

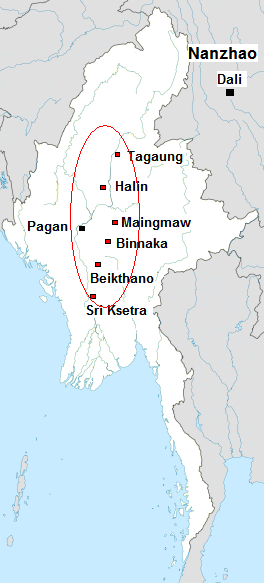

The Pyu realm in the red zone

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Sri Ksetra, Halin, Beikthano, Pinle, Binnaka | ||||||||

| Common languages | Pyu | ||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism, Mahayana Buddhism, Tantric Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||||||

|

• Earliest Pyu presence in Upper Burma

|

c. 2nd century BCE | ||||||||

|

• Beikthano founded

|

c. 180 BCE | ||||||||

|

• Pyu converted to Buddhism

|

4th century | ||||||||

|

• Burmese calendar begins

|

22 March 638 | ||||||||

|

• 2nd Sri Ksetra Dynasty founded

|

25 March 739 | ||||||||

|

• Rise of Pagan Empire

|

c. 1050 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| Location | Myanmar |

| Includes |

|

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii)(iii)(iv) |

| Inscription | 2014 (38th Session) |

| Area | 5,809 ha (14,350 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 6,790 ha (16,800 acres) |

The Pyu city-states (Burmese: ပျူ မြို့ပြ နိုင်ငံများ) were a group of important cities in what is now Upper Burma (Myanmar). They existed for about 1,000 years, from around 200 BCE to the mid-11th century CE. The Pyu people, who spoke a Tibeto-Burman language, were the first known inhabitants of this area. This long period is often called the Pyu millennium. It connects the Bronze Age to the time when the Pagan Kingdom became powerful in the late 9th century.

Most major Pyu cities were in three fertile areas of Upper Burma. These were the Mu River Valley, the Kyaukse plains, and the Minbu region. These areas were near where the Irrawaddy and Chindwin Rivers meet. Archaeologists have found five large walled cities: Beikthano, Maingmaw, Binnaka, Halin, and Sri Ksetra. Many smaller towns have also been found.

Halin, founded in the 1st century CE, was the biggest city until about the 7th or 8th century. Then, Sri Ksetra took its place. Sri Ksetra was near modern Pyay and was twice as large as Halin. It became the most important Pyu center. Only Halin, Beikthano, and Sri Ksetra are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Other sites might be added later.

The Pyu kingdom was part of a trade route between China and India. Indian culture greatly influenced the Pyu. They adopted Buddhism and many ideas about culture, building, and government. These ideas had a lasting impact on Burma. The Pyu calendar, based on the Buddhist calendar, later became the Burmese calendar. The Pyu script, which came from the Brahmi script, might have been the basis for the Burmese script.

This ancient civilization ended in the 9th century. The Pyu cities were attacked many times by invaders from the Kingdom of Nanzhao. The Bamar people then built a town called Bagan (Pagan). Pyu settlements continued to exist for about 300 more years. However, the Pyu people slowly became part of the growing Pagan Kingdom. The Pyu language was still spoken until the late 12th century. By the 13th century, the Pyu people had become part of the Burman ethnic group. Their history and legends also became part of the Bamar stories.

Contents

- How Did the Pyu Civilization Begin?

- What Have Archaeologists Discovered?

- How Did the Pyu Cities Decline?

- Important Pyu Cities

- How Did the Pyu People Live?

- Pyu Culture and Beliefs

- Pyu Architecture and City Design

- Who Lived in Pyu Cities?

- How Were Pyu Cities Governed?

- What is the Current Status of Pyu Sites?

- See also

How Did the Pyu Civilization Begin?

Based on what archaeologists have found, the earliest cultures in Burma existed as far back as 11,000 BCE. These early people lived mainly in the dry central area near the Irrawaddy River. Burma's Stone Age, called the Anyathian, was similar to the Paleolithic eras in Europe. Tools from the Stone Age, dating from 10,000–6000 BCE, have been found in three caves near Taunggyi.

Around 1500 BCE, people in this region learned to turn copper into bronze. They also grew rice and raised chickens and pigs. They were among the first people in the world to do these things. By 500 BCE, settlements where people worked with iron appeared south of modern Mandalay. Archaeologists have found bronze-decorated coffins and burial sites with earthenware. Evidence from the Samon River Valley suggests that rice-growing communities traded with China between 500 BCE and 200 CE.

Around the 2nd century BCE, the Tibeto-Burman-speaking Pyu people arrived. They came into the Irrawaddy River Valley from what is now Yunnan, China. They used the Taping and Shweli Rivers to travel. It is believed that the Pyu originally came from the Qinghai Lake area in China. The Pyu were the first people in Burma for whom we have written records. They built settlements throughout the plains where the Irrawaddy and Chindwin Rivers meet.

The Pyu kingdom was long and narrow. It stretched from Sri Ksetra in the south to Halin in the north. Binnaka and Maingmaw were to the east. Records from China's Tang dynasty mention 18 Pyu states. Nine of these were walled cities, covering many districts.

What Have Archaeologists Discovered?

The Pyu were among the first people in Southeast Asia to use and adapt Brahmic scripts. They used these scripts to write down their language, even inventing special marks for tones. Pyu cities had a unique design. They were walled, often with a water tank inside or outside the walls.

Archaeological findings show that the Pyu were skilled at managing water. They used irrigation systems based on their knowledge of local conditions. Many important stone writings in the Pyu language have been found. These are at Sri Ksetra, Hanlin, near Pinle (Hmainmaw), and Pagan (Bagan). These findings show that people lived in these areas between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE.

Sri Ksetra, for example, had fields, irrigation canals, and water tanks. It also had iron-working sites, monuments, and markets. These discoveries show a strong belief system, especially in how they cared for their dead. Old photos show nine large burial terraces outside the southern city walls. Ancient Buddhist monuments and cemeteries have also been found.

So far, archaeologists have found 12 walled cities. Five of these are large, and there are many smaller settlements. These are located in the three main irrigated areas of ancient Burma. These Pyu cities existed at the same time as other early kingdoms in Southeast Asia. These include the Kingdom of Funan in Cambodia and Dvaravati in Thailand. These early states set the stage for the "classical kingdoms" that rose later.

How Did the Pyu Cities Decline?

The Pyu civilization lasted for almost 1,000 years, until the early 9th century. Then, a new group of "swift horsemen" from the north arrived. These were the Burmans (Mranma) from the Nanzhao Kingdom. They began raiding the upper Irrawaddy valley. Chinese records from the Tang Dynasty say that Nanzhao raids started as early as 754 or 760 CE. By 763, the Nanzhao king had conquered the upper Irrawaddy Valley.

Nanzhao raids became more frequent in the 9th century. They raided in 800–802 and again in 808–809. Finally, Chinese records state that in 832, Nanzhao warriors attacked the Pyu country. They took 3,000 Pyu prisoners from Halin.

However, the Pyu people and their culture did not simply disappear. The Pyu kingdom was large, with many walled cities. This means there were many more people than just 3,000. There is no strong evidence at Sri Ksetra or other Pyu sites that shows a sudden, violent end. It is more likely that these raids weakened the Pyu states. This allowed the Burmans to move into Pyu lands.

Evidence shows that the Burman migration into the Pyu areas was slow. Radiocarbon dating shows that people were still active at Halin until about 870 CE. This was nearly 40 years after the reported Nanzhao attack. Burmese historical records say the Burmans founded the city of Pagan in 849. But the oldest scientific dating of Pagan's walls points to 980 CE. The main walls date to around 1020 CE.

By the late 10th century, the Burmans had taken control of the Pyu kingdom. They went on to establish the Pagan Empire in the mid-11th century. This empire united the Irrawaddy valley for the first time. The Pyu left a lasting impact on Pagan. The Burman rulers of Pagan even claimed to be descendants of the Pyu kings. Pyu settlements remained in Upper Burma for about 300 more years. But the Pyu people were slowly absorbed into the growing Pagan Empire. The Pyu language was still spoken until the late 12th century. By the 13th century, the Pyu had become part of the Burman ethnic group and their distinct identity faded.

Important Pyu Cities

Archaeologists have found 12 walled cities so far. Five of these were the largest Pyu states: Beikthano, Maingmaw, Binnaka, Halin, and Sri Ksetra.

Beikthano: The Oldest City

Beikthano (Burmese: ဗိဿနိုး) is in the Minbu region. It had direct land access to the fertile Kyaukse plains. This is the oldest city site found and studied by scientists. Its remains, including buildings, pottery, tools, and skeletons, date from 200 BCE to 100 CE.

The city is named after the Hindu god Vishnu. It might have been the first capital of a unified state in Burma. It was a large, fortified settlement. Its rectangular walls were about 3 kilometers long and 1 kilometer wide. The walls were 6 meters thick. Scientists have dated them to between 180 BCE and 610 CE. Like most later cities, the main entrance led to the palace, which faced east. Stupas (Buddhist shrines) and monasteries have also been found inside the city walls.

Maingmaw: A Circular City

Maingmaw (မိုင်းမော), also called Pinle, is in the Kyaukse region. It was circular and may date back to the first millennium BCE. It is one of the largest ancient cities on the Kyaukse plains, about 2.5 kilometers across.

Maingmaw has two inner walls. The outer one is square, and the inner one is circular. This design, a circle within a square, might represent the zodiac or a view of the heavens. Mandalay, a 19th-century city, was also designed this way. A 19th-century temple, Nandawya Paya, stands near the center. It was likely built on the ruins of an older temple. A canal cuts through the city, which may be from the same time period.

Excavations have uncovered many items. These include jewelry, silver coins, and burial urns. Many of these items are very similar to those found at Beikthano and Binnaka.

Binnaka: Maingmaw's Neighbor

Binnaka (ဘိန္နက) was also in the Kyaukse region. It was very similar to Maingmaw. Its brick buildings had the same layout as those at Beikthano and other Pyu sites.

Archaeologists have found many interesting things here. These include items from before Buddhism, gold necklaces, and stone images of animals. They also found unique Pyu pottery and clay tablets with writing similar to the Pyu script. Various types of beads made from onyx, amber, and jade were also discovered. Silver coins, identical to those from Beikthano and Maingmaw, were found. Stone molds for making silver and gold flowers, a gold armlet, and burial urns were also present.

Both Maingmaw and Binnaka might have existed at the same time as Beikthano. Old records mention Binnaka's ruler as being responsible for the fall of Tagaung. Tagaung is believed to be the original home of Burmese speakers. Binnaka was inhabited until about the 19th century.

Halin: The Northern Pyu City

Halin or Halingyi (ဟန်လင်းကြီး) is in the Mu valley. This is one of the largest irrigated areas of ancient Burma. It is the northernmost Pyu city found so far. The oldest items from Halin, its wooden gates, date back to 70 CE.

The city was rectangular with curved corners and brick walls. The excavated walls are about 3.2 kilometers long north-south and 1.6 kilometers east-west. At 664 hectares, Halin was almost twice the size of Beikthano. It had four main gates facing the cardinal directions and a total of 12 gates, based on the zodiac. A river or canal flowed through the city. A moat (ditch) surrounded most of the city, except for the south where land was dammed to create water reservoirs.

Halin's city design influenced later Burmese cities like Pagan and Mandalay. It also influenced the Siamese city of Sukhothai. For example, the number and arrangement of gates were copied. The design of Halin's temples also influenced the temples built in Pagan from the 11th to 13th centuries. Writings found at Halin show the earliest Pyu script in Burma. This script was based on an older version of the Brahmi script from India.

Halin was known for producing salt, a very valuable product. Around the 7th century, Sri Ksetra became the most important Pyu city, taking Halin's place. Chinese accounts say Halin remained important until the 9th century. At that time, the Pyu kingdom was attacked repeatedly by the Nanzhao Kingdom. Chinese records state that Nanzhao warriors destroyed Halin in 832 CE. They took 3,000 people away. However, scientific dating shows human activity continued there until about 870 CE.

Sri Ksetra: The Last Capital

Sri Ksetra or Thaye Khittaya (သရေခေတ္တရာ), meaning "Field of Fortune," is located 8 kilometers southeast of Pyay. It was the last and southernmost Pyu capital. The city was founded between the 5th and 7th centuries. However, recent digs have found pottery with Buddhist symbols from around 340 CE. Pyu cremation burials from around 270 CE have also been found.

Sri Ksetra likely became the most important Pyu city by the 7th or 8th century. It kept this status until the Burmans arrived in the 9th century. The city was home to at least two, and possibly three, ruling families. The first family, the Vikrama Dynasty, is thought to have started the Pyu calendar. This calendar, beginning on March 22, 638, later became the Burmese calendar. A second ruling family was founded by King Duttabaung on March 25, 739.

Sri Ksetra is the largest Pyu site found so far. It was larger than 11th-century Pagan or 19th-century Mandalay. Sri Ksetra was circular, more than 13 kilometers around, and about 1,400 hectares in size. The city's brick walls were 4.5 meters high. It had 12 gates, with large statues of devas (deities) guarding the entrances. A pagoda stood at each of the four corners.

The city also had curving gateways, similar to those at Halin and Beikthano. In the center was what scholars believe was the palace site. It was rectangular, about 518 by 343 meters. This design symbolized a mandala and a horoscope. Only the southern half of the city had the palace, monasteries, and houses. The entire northern half was made up of rice fields. This design, along with moats and walls, helped the city survive long sieges.

Sri Ksetra was an important trading hub between China and India. It was located on the Irrawaddy River, not far from the sea. Ships from the Indian Ocean could travel up to Pyay to trade with the Pyu and China. Trade with India brought strong cultural connections. Sri Ksetra has the most evidence of Theravada Buddhism. Art shows influences from Southeast and Southwest India. Later, in the 9th century, there were influences from the Nanzhao Kingdom.

Much of what the Chinese wrote about the Pyu states came from Sri Ksetra. Chinese travelers Xuanzang (in 648) and Yijing (in 675) mentioned Sri Ksetra in their writings about Buddhist kingdoms. Chinese histories also note that an embassy from the Pyu capital visited the Tang court in 801.

Smaller Pyu Settlements

A smaller but important Pyu site is Tagaung in northern Burma. It is about 200 kilometers north of Mandalay. Pyu items, including burial urns, have been found there. Tagaung pottery is similar in size to other Pyu items but looks different. This might mean it had influences from other places. Tagaung is important because Burmese historical records say it was the home of the first Burmese kingdom. Most Pyu sites, except Beikthano and Sri Ksetra, have not been fully explored.

The lost city called Pinle Pyu (meaning "Sea Pyu") is said to have been near the sea. Some archaeologists think ruins near Ingapu, Ayeyarwady Region might be Pinle Pyu. The writing found there uses Brahmi script, suggesting it is very old. More research is needed to confirm this. Other finds nearby, like Stone Age tools and fossilized footprints, suggest the area is very ancient.

Many Pyu settlements have been found in Upper Burma, near the mouth of the Mu river. One notable site is Ayadawkye Ywa, west of Halin. Further south, the Wati site is the remains of a circular walled city.

There were also Pyu settlements in Lower Burma. The Sagara (Thagara) site in Dawei is similar to Tagaung. Digs in 2001 found items like clay urns. Near Sagara, the Mokti site also has similar items. The stupa in Sagara and tablets from Mokti show Pyu cultural traits.

How Did the Pyu People Live?

Farming and Food

The Pyu cities' economy was based on farming and trade. All major Pyu settlements were in the three main irrigated areas of Upper Burma. These were the Mu valley (Halin), the Kyaukse plains (Maingmaw and Binnaka), and the Minbu district (Beikthano and Sri Ksetra). The Pyu built irrigation systems. Later, the Burmans continued these projects. King Anawrahta of Pagan built irrigation systems in these areas in the 1050s. This made them the main rice-growing regions of Upper Burma. The Pyu grew rice, possibly a type called Japonica.

Trade and Money

The Pyu kingdom was an important trading center between China and India. This was during the first 1,000 years CE. Two main trade routes passed through the Pyu states. An overland route between China and India existed across northern Burma as early as 128 BCE. Roman Empire embassies to China used this route in 97 CE and 120 CE.

However, most trade happened by sea through the southern Pyu states. At that time, these cities were close to the sea because the Irrawaddy delta had not yet fully formed. Pyu items have been found in coastal towns as far south as the upper Tenasserim coast. These ports connected the sea trade route to the overland route to China through Yunnan.

The Pyu states traded across Southeast Asia, South Asia, and China. Items from northwest India, Java, and the Philippines have been found at Beikthano. Pyu items have also been found along the coasts of Arakan, Lower Burma, and as far east as Óc Eo in southern Vietnam. The Pyu also traded and had diplomatic ties with China. In 800 and 801–802, Sri Ksetra sent an official group, including 35 musicians, to the Tang court. The Chinese said the Pyu used gold and silver coins. Only silver coins have survived.

A special feature of the Pyu states was their silver coins. These coins started in the Pegu area around the 5th century. They were a model for most coins in mainland Southeast Asia for the next 1,000 years. The earliest coins had a conch shell on one side and a Srivatsa (a symbol) on the other. Many coins had a small hole, suggesting they might have been used as amulets. After the Pyu period ended in the late 9th century, coins were not used in Burmese kingdoms again until the 19th century.

Pyu Culture and Beliefs

Religion

Indian culture greatly influenced the Pyu city-states. This influence was strongest in the southern Pyu area, where most sea trade with India happened. The names of southern cities, like Sri Ksetra and Beikthano, came from Pali or Sanskrit. The kings at Sri Ksetra used titles like Varmans and Varma. Indian culture also affected northern Pyu cities. Burmese historical records claim that the founding kings of Tagaung were related to the Sakya clan of the Buddha himself.

By the 4th century, most Pyu people were Buddhist. However, archaeological finds show that their older, pre-Buddhist practices remained strong for centuries. According to ancient texts and Chinese records, the main religion of the Pyu was Theravada Buddhism. This type of Buddhism likely came from the Andhra region in southeast India. It was the main Theravada school in Burma until the late 12th century.

Archaeological finds also show that Tantric Buddhism, Mahayana Buddhism, and Hinduism were present. Figures important in Mahayana Buddhism, like Avalokiteśvara (called Lawkanat in Burmese), Tara, and others, were part of Pyu art. Various Hindu gods and symbols, like Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, Garuda, and Lakshmi, have been found, especially in Lower Burma.

Some non-Theravada practices, like ceremonial cattle sacrifice, were common in Pyu life. Also, there seemed to be more nuns and female students than in later times. This might suggest that women had more freedom before Buddhism became so strong. The Pyu combined their old practices with Buddhist ones. They placed the ashes of their dead in pottery and stone urns. These were buried in or near isolated stupas (shrines). This was an early Buddhist practice for important people.

Even though their beliefs were a mix of many traditions, the Pyu were known for being peaceful. Chinese records describe them as kind people who rarely went to war. They wore cotton instead of silk so they wouldn't have to kill silkworms. Many Pyu boys became monks from age seven until they were 20. This peaceful description from the Chinese was just a snapshot and might not show all aspects of life in the Pyu cities.

Language and Writing

The Pyu language was a Tibeto-Burman language, similar to Old Burmese. However, Sanskrit and Pali were also used as court languages. Chinese records say that the 35 musicians who visited the Tang court in 800–802 sang in the Fan (Sanskrit) language. Many important writings were in Sanskrit and/or Pali, along with the Pyu script.

Recent studies suggest that the Pyu script, based on the Brahmi script, might be the source of the Burmese script. This is still being debated. Pyu sites have yielded many different Indian scripts. These include King Ashoka's edicts from the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, and Gupta script and Kannada script from the 4th to 6th centuries CE.

Calendar System

Besides religion, the Pyu also adopted scientific and astronomy knowledge from India. Chinese records say the Pyu knew how to make astronomical calculations. The Pyu calendar was based on the Buddhist calendar. Two main eras were used. The first was the Sakra Era, adopted in 80 CE. A second calendar was adopted at Sri Ksetra in 638 CE, replacing the Sakra Era. This calendar, starting on March 22, 638, later became the Burmese calendar. It is still used in Myanmar today.

Pyu Architecture and City Design

Water Systems

Pyu building methods greatly influenced later Pagan and Burmese architecture. The ways they built dams, canals, and weirs (small dams) in ancient Upper Burma came from the Pyu and Pagan eras. The Burmans likely brought new ways to manage water, especially canal building. This became the main way to irrigate land in the Pagan era.

City Planning

Pyu city plans used both square/rectangle and circular shapes. These were a mix of local and Indian designs. The circular patterns inside the cities are thought to be Pyu. The rectangular or square outer walls and the use of 12 gates were Indian in origin. Historians believe that adopting Indian city planning ideas meant believing in a "world axis." This axis connected the center of a city to the city of the Gods above. This was meant to bring good fortune to the kingdom. Pyu city planning was the basis for later Burmese city and palace designs, even up to 19th-century Mandalay.

Temple Design

From the 4th century onward, the Pyu built many Buddhist stupas and other religious buildings. The styles, layouts, brick sizes, and building techniques of these structures show influence from the Andhra region of India. Some evidence of contact with Sri Lanka is seen in "moonstones" found at Beikthano and Halin. By about the 7th century, tall, cylindrical stupas like the Bawbawgyi, Payagyi, and Payama appeared at Sri Ksetra.

Pyu architecture greatly influenced later Burmese Buddhist temple designs. For example, temples at Sri Ksetra, like the Bebe and Lemyethna, were early versions of the hollow gu temples of Pagan. The layout of the 13th-century Somingyi Monastery at Pagan was almost the same as a 4th-century monastery at Beikthano. The solid stupas of Sri Ksetra were models for Pagan's stupas, like the Shwezigon, Shwehsandaw, and Mingalazedi. These, in turn, influenced the famous Shwedagon in modern Yangon.

Who Lived in Pyu Cities?

The cities were mainly home to the Pyu people, who spoke a Tibeto-Burman language. Like their relatives, the Burmans, they are believed to have come from the Qinghai and Gansu provinces in north-central China, through Yunnan. Extensive trade with other regions attracted many Indians and Mon, especially in the south. In the north, some Burmans might have entered the Pyu kingdom from Yunnan as early as the 7th century. However, modern scholars believe that large numbers of Burmans did not arrive until the mid-to-late 9th century, or even as late as the 10th century.

The total population of the Pyu kingdom was probably a few hundred thousand people. For comparison, 17th and 18th century Burma, which was about the size of modern Myanmar, had only about 2 million people.

How Were Pyu Cities Governed?

The Pyu settlements were ruled by independent chiefs. The chiefs in larger cities later called themselves kings. They set up courts that were largely based on Indian (Hindu) ideas of monarchy. However, not all Hindu ideas, like divine kingship (where a king is seen as a god), were fully adopted because of the presence of Theravada Buddhism. It is not clear if larger cities controlled smaller towns. Burmese historical records mention alliances between states, such as one between Beikthano and Sri Ksetra. Generally, each Pyu city-state seemed to control only its own city.

The Pyu cities were very large (660 to 1,400 hectares) compared to Pagan (only 140 hectares). This suggests that most of the population lived inside the city walls, which Chinese records also confirm. Archaeological finds in Pagan show Pyu items in several settlements within the walled area until about 1100 CE. After this time, there was a shift towards building many monuments and people started living outside the walls.

What is the Current Status of Pyu Sites?

Most Pyu sites, except Sri Ksetra and Beikthano, have not been fully explored. The Ministry of Culture's Department of Archaeology is responsible for caring for these sites. In November 2011, the Department planned a museum at Sri Ksetra. They also worked with UNESCO to get recognition for Sri Ksetra, Beikthano, and Halin as World Heritage Sites. These three ancient cities were recognized as World Heritage Sites in 2014.

See also

In Spanish: Civilización pyu para niños

In Spanish: Civilización pyu para niños

- History of Burma

- Mon city-states

- Pagan Dynasty

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |