History of Sierra Leone facts for kids

Sierra Leone is a country in West Africa that has a very long history! People have lived there for at least 2,500 years. The Limba tribe was one of the first groups known to live in the area. Because of its thick rainforests, Sierra Leone was a safe place for people escaping conflicts and wars in other parts of Africa.

The name "Sierra Leone" was given by a Portuguese explorer named Pedro de Sintra in 1462. He saw the hills around what is now Freetown and called them Serra Lyoa, which means "Lioness Mountain." The Freetown area had a great natural harbor, which became important for ships trading along the coast and across the Atlantic Ocean.

In the mid-1500s, a group called the Mane people invaded Sierra Leone. They were strong warriors and took control of many coastal areas. The Mane people eventually mixed with the local tribes, but different chiefdoms (areas ruled by chiefs) often fought with each other. Many people captured in these fights were sold to European slave traders. The Atlantic slave trade had a huge impact on Sierra Leone for centuries.

Later, in the 1800s, when the slave trade was made illegal, Sierra Leone became a center for efforts against slavery. British people who wanted to end slavery helped create a colony in Freetown for Black Loyalists – African Americans who had fought for Britain during the American Revolutionary War. This colony grew quickly as more freed Africans and soldiers settled there. Their descendants are known as the Creoles or Krios.

During the time when Britain ruled Sierra Leone, the British and Creoles expanded their control, trying to keep peace for trade and stop slave trading. In 1895, Britain officially declared Sierra Leone a "protectorate," which meant they would rule it. This led to a war called the Hut Tax War of 1898. Over time, people in Sierra Leone pushed for more rights and fairness.

Sierra Leone has played a big role in Africa's fight for freedom. In the 1950s, a new government system brought the different parts of Sierra Leone together. On April 27, 1961, Sierra Leone became independent from the United Kingdom and joined the Commonwealth of Nations. However, differences between ethnic groups like the Mende, Temne, and Creoles have sometimes caused problems, leading to periods of strict government or even civil war.

Contents

- Early History of Sierra Leone

- European Contact and the Slave Trade

- Mane Invasions and Their Impact

- British Influence and the Freetown Colony

- Colonial Era (1808–1961)

- Independence and Early Years (1960–1968)

- Stevens' Government and One-Party Rule (1968–1985)

- Momoh's Government and Civil War (1985–1991)

- Civil War (1991–2002)

- Sierra Leone Today (2002–Present)

- See also

Early History of Sierra Leone

Archaeological discoveries show that people have lived in Sierra Leone for at least 2,500 years. Different groups of people moved into the area from other parts of Africa over time. By the 800s, people in Sierra Leone were using iron, and by the late 900s, coastal tribes were practicing agriculture.

Sierra Leone's thick tropical rainforest helped keep it somewhat separate from other African cultures and the spread of Islam. This made it a safe place for people trying to escape from powerful kingdoms and religious wars.

Europeans first came to Sierra Leone in the 1400s. In 1462, the Portuguese explorer Pedro de Sintra mapped the hills around what is now Freetown Harbor. He called the unusual shape of the mountains Serra Lyoa, which means "Lioness Mountain."

At that time, many different independent groups lived in the country. They spoke various languages, but their religions were similar. Along the coast, there were Bulom-speakers, Loko-speakers, Temne-speakers, and Limba-speakers. In the hilly areas to the north, lived the Susu and Fula tribes. The Susu often traded with the coastal people, bringing salt, clothes, iron goods, and gold.

European Contact and the Slave Trade

Portuguese ships started visiting Sierra Leone regularly in the late 1400s. For a while, they even had a fort on the north side of the Freetown estuary. This estuary is one of the world's largest natural deep-water harbors and a good place for sailors to find shelter and fresh water. Some Portuguese sailors stayed, trading and marrying local people.

The Impact of Slavery

Slavery, especially the Atlantic slave trade, greatly affected Sierra Leone from the late 1400s to the mid-1800s. It changed society, the economy, and politics.

Before Europeans arrived, there was some local slavery in West Africa, often linked to the trans-Saharan trade. However, when the Portuguese first came to Sierra Leone, slavery among the local African people was thought to be rare. Historians say that if it was common, the Portuguese would have written about it in their detailed reports.

One type of local slavery was when:

a person in trouble in one kingdom could go to another and place himself under the protection of its king, whereupon he became a "slave" of that king, obliged to provide free labour and liable for sale.

These people likely kept some rights and could improve their status over time.

When Europeans started colonies in the Americas, they needed many workers. This led them to seek enslaved people from Africa. At first, European slave traders raided coastal villages. But soon, they made deals with local leaders, who would sell people from rival tribes or those considered undesirable.

This early slave trade was mainly for export. Using enslaved people for labor within Africa became more common later, especially among coastal chiefs in the late 1700s. For example, William Cleveland, a Scottish leader in Africa, had a large "slave town" where people grew huge rice fields.

Historians suggest that local slavery might have grown because:

- Not all war captives offered for sale were bought by Europeans, so their captors used them for local labor.

- There was often a group of enslaved people waiting to be sold, who were put to work.

- Europeans provided an example of using enslaved labor.

- The sale of local goods to Europeans created a greater need for farm workers, and slavery was a way to get this labor.

Local African slavery was generally less harsh than the slavery on plantations in the Americas. Enslaved people were often seen as part of the owner's household and had some rights. They might get small plots of land for their own use and could even earn enough to buy their own enslaved person. Sometimes, an enslaved person married into the owner's family and gained trust. Their children often became almost like free people.

In the 1700s, people were rarely sold into slavery unless they were criminals or war captives. Another form of dependence was called pawning. A person in debt might offer a child or another dependent to a wealthy person to work off the debt. These people became dependents and, if not redeemed, their children eventually became part of the master's extended family, often seen as brothers and sisters to the master's own children.

Some experts believe that "subject," "servant," or "dependent" might be better words than "slave" for these local practices. Domestic slavery in Sierra Leone was officially ended in 1928. However, many former enslaved people stayed in the villages where they had lived.

The export of enslaved people from Sierra Leone was a major business from the late 1400s to the mid-1800s. By 1789, it was estimated that 74,000 enslaved people were exported from West Africa each year. The Atlantic slave trade was gradually outlawed by Western nations starting in 1808.

Mane Invasions and Their Impact

The Mane invasions in the mid-1500s greatly changed Sierra Leone. The Mane, a warrior group from the Mande language family, were well-armed and organized. They moved south into Sierra Leone, conquering as they went. They added many conquered people to their army, so by the time they reached Sierra Leone, most of their soldiers were local people, with the Mane as commanders.

The Mane used small bows and large shields made of reeds. They wore loose cotton shirts with many feathers. By 1545, they had reached Cape Mount, near modern-day Sierra Leone. Their conquest of Sierra Leone took 15 to 20 years, bringing almost all coastal people under their rule. Today's population of Sierra Leone still shows the effects of these invasions. For example, the Temne kept their language but were ruled by Mane kings. The Loko and Mende languages are similar and mostly Mande, likely due to Mane conquest.

The Mane invasions made Sierra Leone more militarized. Before, the local people were not very warlike. But after the invasions, bows, shields, and knives like those used by the Mane became common. Villages became fortified with strong walls made of logs that often took root and grew, creating living walls that were very hard to break through.

After the invasions, the Mane chiefs often fought among themselves. This fighting continued even after the Mane mixed with the local population. Historians believe that the desire to capture people to sell as slaves to Europeans was a big reason for these conflicts. However, other reasons like gaining land and political power also played a role. The wars were not always very deadly, often involving small ambushes rather than large battles.

In these times, each large village and its smaller settlements were led by a chief. The chief had a private army. Sometimes, several chiefs would form a group, with one acting as a king or high chief. This king would help if one of his chiefs was attacked and could settle disputes.

Despite their political divisions, the people of Sierra Leone were united by their culture. One important part of this was the Poro, a group common to many kingdoms and ethnic groups. It's often called a "secret society" because its rituals are only for members. However, most men (and some women) are members. The Poro helped guide males from puberty to manhood and provided some education. It also had a role in trade and banking.

The Mane invasions greatly affected the local people, who lost their political freedom. Trade with the interior was disrupted, and many were sold as slaves. However, the invasions also brought improved ironworking techniques.

British Influence and the Freetown Colony

By the 1600s, the influence of Portugal in West Africa began to fade. English and Dutch traders started to become more important in Sierra Leone. In 1628, English merchants set up a trading post near Sherbro Island, about 50 km (30 miles) south-east of Freetown. They traded in ivory, enslaved people, and a type of hard wood called camwood.

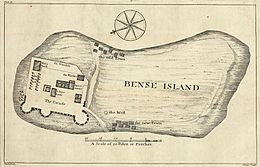

In 1663, the Royal African Company (RAC) was given permission by the English king to trade in Africa. They set up trading posts on Sherbro Island and Tasso Island. These posts were attacked by the Dutch and French navies, and by pirates. After an attack, the RAC moved its main trading post to Bunce Island, which was easier to defend.

Europeans paid local kings "Cole" for rent, tribute, and trading rights. At this time, African leaders still had military power. In 1714, a king even seized RAC goods because of a breach of diplomatic rules. Local Afro-Portuguese merchants often acted as middlemen in trade. Bunce Island became an important center for the slave trade, especially for sending enslaved Africans to the southern American colonies.

The Province of Freedom (1787)

In 1787, a plan was made to settle some of London's "Black Poor" in Sierra Leone. This group included African Americans who had been freed after seeking safety with the British Army during the American Revolution, as well as other people from the West Indies, Africa, and Asia living in London. This new settlement was called the "Province of Freedom."

The first group of about 400 formerly enslaved Black Britons arrived in Sierra Leone on May 15, 1787. They started Granville Town on land bought from local Koya Temne chiefs. However, half of the settlers died in the first year due to disease. The local chiefs also attacked the settlement, burning it down in 1789. Only 64 settlers remained.

Freetown Colony (1792)

The idea for the Freetown Colony started in 1791 with Thomas Peters, an African American who had settled in Nova Scotia, Canada. He traveled to England to report problems faced by Black Loyalists there. Peters learned about the Sierra Leone Company's plan for a new settlement in Sierra Leone.

Lieutenant John Clarkson was sent to Nova Scotia to recruit settlers. He worked with Peters to gather 1,196 former American slaves from free African communities in Nova Scotia. Most had escaped plantations in Virginia and South Carolina.

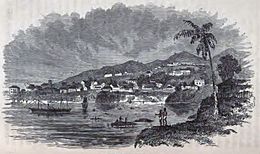

These settlers sailed in 15 ships and arrived in Sierra Leone in early 1792. They were to build Freetown on the old site of Granville Town, which had become overgrown. On March 11, 1792, a white preacher named Nathaniel Gilbert and an African American preacher named David George led a prayer and sermon under a large cotton tree. The land was dedicated and named 'Free Town'. This was the beginning of the political entity of Sierra Leone.

In 1800, some of the Nova Scotian settlers rebelled. The arrival of over 500 Jamaican Maroons (free black people from Jamaica) helped put down the rebellion. The Maroons were given their own district called Maroon Town.

Britain outlawed the slave trade throughout its empire in 1807. The Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron, based in Freetown, actively stopped ships involved in the illegal slave trade. The enslaved people found on these ships were freed in Freetown and were called 'Liberated Africans'.

Over time, the Creole (Krio) ethnic group formed from the descendants of these different groups of freed people who settled in Freetown.

Colonial Era (1808–1961)

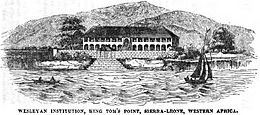

In 1808, Sierra Leone officially became a British Crown Colony. Freetown became the capital of British West Africa. The city grew quickly as more freed slaves and soldiers settled there.

British Control and the Hinterland

In the early 1800s, Sierra Leone was a small colony around Freetown. Most of the land was still controlled by local African people like the Mende and Temne. But over the 1800s, the British and Creoles in Freetown gradually gained more control through trade, treaties, and military actions.

The British wanted peace to ensure trade wasn't interrupted. They often paid chiefs to keep the peace, open roads, allow customs duties, and settle disputes. After Britain banned the slave trade in 1807, treaties also required chiefs to stop slave trading. Stopping slave trading and local wars went together, as wars fueled the slave trade.

When peaceful talks failed, the British used their army and navy to attack chiefs who didn't follow their rules. They would bombard a town and then burn it. They often invited local enemies of the attacked group to join them.

In the 1880s, Britain increased its efforts to control the hinterland because of the "Scramble for Africa" – a race among European powers to claim African territory. To stop France from taking over areas they wanted, Britain made new agreements with chiefs, forbidding them from dealing with other European powers without British permission.

The British Protectorate (1895)

In 1895, Britain officially declared the territory around the Colony a British Protectorate. This meant Britain would rule it. Most chiefs did not agree to this willingly. Many had signed friendship treaties, but these did not mean they were giving up their power to Britain. The creation of the Protectorate was more like Britain simply taking control.

Almost every chiefdom in Sierra Leone resisted this British takeover. The new laws abolished the title of "King" and replaced it with "Paramount Chief." Chiefs, who used to be chosen by their communities, could now be removed or appointed by the British Governor. Most of their judicial powers were taken away and given to British "District Commissioners." The Governor also introduced a house tax on every home in the Protectorate. These changes greatly reduced the power and prestige of the chiefs.

Hut Tax War of 1898

In 1898, two rebellions broke out against British rule because of the new hut tax. Governor Frederic Cardew introduced the tax to pay for the colonial government, but many people couldn't afford it. In February 1898, an attempt to arrest Temne chief Bai Bureh led him and his followers to revolt. Bureh's forces attacked British officials and Creole traders.

Bureh offered peace twice, but Cardew refused unless Bureh surrendered without conditions. Bureh's forces fought a skilled guerrilla war, making it difficult for the British. The fighting paused during the rainy season but resumed in October. Bureh was captured in November.

A second, larger uprising happened in the southeast in April, where many Europeans and Creoles were killed. This rebellion was less organized but very fierce. It was mostly put down within two months, though some fighting continued until August 1899. Leaders like Bureh were exiled, and many rebels were executed. In 1905, Bureh was allowed to return to Sierra Leone.

Colonial Period Dissent (1898–1956)

After the Hut Tax War, there was no more large-scale military resistance. However, people continued to resist and express their disagreement in other ways. The Creoles, who had many educated professionals and business people, often spoke out against the government through newspapers. In 1924, a new constitution allowed for some elected representatives for the first time.

Sierra Leone also developed a strong trade union movement, and strikes often led to riots. People were also angry at the tribal chiefs, whom the British had made into government officials. These chiefs were forced to collect taxes and provide forced labor for the colonial government. Chiefs who didn't cooperate were replaced.

Throughout the 1900s, there were many riots against tribal chiefs. After major riots in 1955, reforms were made, including the complete end of forced labor and a reduction in the chiefs' powers.

Sierra Leone remained divided into a Colony and a Protectorate, each with its own political system. This caused tension, especially when proposals were made in 1947 to unite them. The Krio people, led by Isaac Wallace-Johnson, opposed this because it would reduce their political power. However, Sir Milton Margai skillfully brought together the educated people from the Protectorate and the paramount chiefs to support a single system. He later used these skills to achieve independence.

In 1951, Margai helped draft a new constitution that united the legislatures and set the stage for Sierra Leone to become independent. In 1953, Sierra Leone gained local ministerial powers, and Margai became Chief Minister. The new constitution created a parliamentary system within the Commonwealth of Nations. In 1957, Sierra Leone held its first parliamentary election, and Margai's party, the Sierra Leone People's Party (SLPP), won.

Sierra Leone in World War II

During World War II, Freetown was a very important port for Allied ships.

Independence and Early Years (1960–1968)

On April 20, 1960, Sir Milton Margai led the Sierra Leonean delegation to London to negotiate for independence with Queen Elizabeth II and the British Colonial Secretary. On April 27, 1961, Britain agreed to grant Sierra Leone independence.

Siaka Stevens, a trade unionist, was the only delegate who refused to sign the Declaration of Independence. He was concerned about a secret defense agreement with Britain and the lack of elections before independence. Stevens was later expelled from his party.

Sir Milton Margai's Leadership (1961–1964)

On April 27, 1961, Sir Milton Margai became Sierra Leone's first prime minister. Sierra Leone kept a parliamentary government and was part of the Commonwealth. The years after independence were good, with money from mineral resources used for development and the founding of Njala University.

Sir Milton Margai was very popular. He was not corrupt and didn't show off his power. His government followed the rule of law and had a system of different political parties. He appointed government officials from various ethnic groups and shared power among political groups and paramount chiefs.

Sir Albert Margai's Leadership (1964–1967)

When Sir Milton Margai died in 1964, his half-brother, Sir Albert Margai, became Prime Minister. Sir Albert was not as popular as his brother and became more authoritarian. He tried to make Sierra Leone a one-party state and was seen as a threat to the power of the paramount chiefs. In 1967, riots broke out in Freetown against his policies, and he declared a state of emergency. He was also accused of corruption and favoring his own Mende ethnic group.

Despite opportunities to stay in power, Sir Albert chose to call for free and fair elections.

Military Coups (1967–1968)

In the 1967 election, Siaka Stevens' party, the All People's Congress (APC), narrowly won. Stevens became Prime Minister on March 21, 1967. However, within hours, he was overthrown in a bloodless military coup led by Brigadier General David Lansana. Lansana, a close ally of Sir Albert Margai, put Stevens under house arrest.

Two days later, other senior military officers, led by Brigadier Andrew Juxon-Smith, took control, arrested Lansana, and suspended the constitution. They formed the National Reformation Council (NRC). On April 18, 1968, another group of officers, the Anti-Corruption Revolutionary Movement (ACRM) led by Brigadier General John Amadu Bangura, overthrew the NRC. They restored the democratic constitution and gave power back to Stevens.

Stevens' Government and One-Party Rule (1968–1985)

Siaka Stevens became Prime Minister in 1968 with high hopes. He promised to unite the tribes under socialist ideas. He worked to improve the country's economy and connect the provinces with the capital. Roads and hospitals were built in the provinces, and paramount chiefs gained more influence in Freetown.

However, Stevens' rule became more authoritarian due to several suspected coup attempts. He was accused of using intimidation to remove the SLPP from elections. To keep the military's support, Stevens kept the popular John Amadu Bangura as head of the armed forces.

In January 1970, Bangura was arrested and charged with plotting a coup. He was found guilty and executed on March 29, 1970. Stevens then appointed Joseph Saidu Momoh, a loyal ally, as the new head of the military.

In March 1971, soldiers loyal to Bangura mutinied, but the uprising was put down. Stevens asked Guinean President Sekou Toure for help, and Guinean soldiers were stationed in Sierra Leone until 1973 to protect the government.

In April 1971, a new constitution made Sierra Leone a republic, and Stevens became president. In the 1973 election, the opposition SLPP boycotted due to problems, and the APC won almost all seats.

Stevens created his own personal security force, the State Security Division (SSD), to protect him and keep him in power. These officers were very loyal to Stevens and were used to stop any rebellion against his government.

In 1974, an alleged plot to overthrow President Stevens failed. In July 1975, 14 senior army and government officials, including Brigadier David Lansana, were executed for attempting a coup. In March 1976, Stevens was re-elected president without opposition.

In 1977, student demonstrations against the government were quickly stopped by the army and SSD. Another general election was held, but it was marked by corruption. The APC won most seats.

In May 1978, the Sierra Leone Parliament, controlled by Stevens' allies, approved a new constitution that made the country a one-party state. All other political parties, including the SLPP, were banned. The government claimed 97% of Sierra Leoneans voted for this, but opposition groups said the votes were rigged and voters were intimidated. This led to more demonstrations, which were also put down.

The first elections under the one-party system were held in 1982. Due to problems, elections in 13 areas were canceled and re-held. Stevens appointed some former SLPP members to his cabinet, including Salia Jusu-Sheriff, hoping to make the APC a truly national party.

Stevens, who had been head of state for 18 years, retired in November 1985. He chose Major General Joseph Saidu Momoh, a loyal ally and fellow Limba, to succeed him. Momoh retired from the military and was elected president without opposition in October 1985.

Stevens is often criticized for being dictatorial and for government corruption. However, he did bring members of different ethnic groups into his government and kept the country safe from civil war and armed rebellion for 18 years. He also often interacted with the people, making surprise visits to markets and waving to crowds.

Momoh's Government and Civil War (1985–1991)

President Momoh started with support because of his military background and his promise to fight corruption. However, his government soon faced criticism for corruption. In March 1987, an alleged coup attempt led to the arrest of over 60 officials, including Vice-president Francis Minah, who was later executed.

In October 1990, due to pressure for reforms, President Momoh created a commission to review the one-party constitution. A new constitution that brought back a multi-party system and guaranteed human rights was approved in 1991. However, many suspected Momoh wasn't serious about reform, as abuses of power continued.

Meanwhile, a rebellion began in eastern Sierra Leone.

Civil War (1991–2002)

The civil war in neighboring Liberia played a big role in the start of fighting in Sierra Leone. Charles Taylor, a Liberian rebel leader, reportedly helped form the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) under former Sierra Leonean army corporal Foday Sankoh. Sankoh had been jailed for mutiny earlier. The RUF rebels entered Sierra Leone in March 1991 and quickly took control of much of Eastern Sierra Leone, including diamond-mining areas. The government, weakened by a struggling economy and corruption, couldn't stop them.

The Momoh government was falling apart. Many officials resigned to form opposition parties. There were suspicions that the ruling party was planning violence before the upcoming elections. Government workers weren't being paid, leading to looting, and schools were closed, leaving many young people without purpose.

NPRC Junta (1992–1996)

On April 29, 1992, a group of young army officers, led by 25-year-old Captain Valentine Strasser, launched a military coup in Freetown. President Momoh fled into exile. The soldiers formed the National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC) with Strasser as its head. The coup was popular at first because it promised peace. However, the NPRC immediately suspended the constitution, banned political parties, limited free speech, and gave soldiers unlimited power to arrest people without trial.

The NPRC fought the RUF rebels, taking back most of the areas they held. In December 1992, an alleged coup attempt against Strasser failed, and 17 soldiers were executed, including some former government officials.

In July 1994, NPRC deputy leader Solomon Musa was arrested and exiled. Strasser accused him of becoming too powerful. Captain Julius Maada Bio replaced Musa as deputy chairman.

Due to internal conflicts, the NPRC's fight against the RUF became less effective. The RUF gained more ground and reached the edge of Freetown by 1994. The NPRC then hired mercenaries from a company called Executive Outcomes. Within a month, these mercenaries pushed the RUF back to the borders and cleared them from the diamond-rich areas.

On January 16, 1996, after about four years in power, Strasser was arrested by his own bodyguards in a coup led by Bio. Strasser was sent into exile. Bio stated that he wanted to return Sierra Leone to a democratic government and end the civil war.

Return to Civilian Rule (1996–1997)

Bio kept his promise and handed power to Ahmad Tejan Kabbah of the SLPP after elections in early 1996. President Kabbah promised to end the civil war. He started talks with the RUF and signed the Abidjan Peace Accord in November 1996.

In January 1997, Kabbah's government ended its contract with the mercenaries, even though a neutral monitoring force hadn't arrived. This allowed the RUF to regroup. RUF leader Sankoh was arrested in Nigeria, and by March 1997, the peace agreement had fallen apart.

AFRC Junta (1997–1998)

On May 25, 1997, a group of soldiers led by Corporal Tamba Gborie freed prisoners from Pademba Road Prison. One of the prisoners, Major General Johnny Paul Koroma, became the leader of the group. Calling themselves the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC), they launched a military coup and sent President Kabbah into exile. Koroma became head of state, suspended the constitution, and banned demonstrations.

Koroma invited the RUF rebels to join his coup. The combined AFRC/RUF forces took over the capital. They declared the war won and began a wave of looting and attacks on civilians.

No country recognized the AFRC Junta. President Kabbah's government-in-exile in Guinea was recognized by the United Nations and other international groups.

The Kamajors, a group of traditional fighters loyal to President Kabbah, defended southern Sierra Leone from the rebels. Both the Kamajors and the rebels committed human rights violations.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), led by Nigeria, sent a military force to defeat the AFRC/RUF junta and bring back President Kabbah. After 10 months, the AFRC junta was driven out of Freetown by the ECOWAS forces. President Kabbah's government was restored in March 1998.

End of Civil War (1998–2001)

Kabbah returned to power. In July 1998, he disbanded the Sierra Leone military. In October 1998, 25 soldiers were executed for their role in the 1997 coup. AFRC leader Johnny Paul Koroma was sentenced to death in his absence.

ECOWAS couldn't fully defeat the RUF, so the international community pushed for peace talks. The Lomé Peace Accord was signed on July 7, 1999, to end the civil war. It controversially granted amnesty to all fighters and gave Sankoh the position of vice president. In October 1999, the United Nations set up the UNAMSIL peacekeeping force to help restore order and disarm the rebels.

In May 2000, when most Nigerian forces had left, the RUF took over 500 peacekeepers hostage. This led to more fighting. British troops were deployed in Operation Palliser to evacuate foreign nationals, but they went further, taking military action to defeat the rebels and restore order. The British were key to ending the civil war. Many Sierra Leoneans consider Tony Blair, the British Prime Minister at the time, a hero.

Between 1991 and 2001, about 50,000 people were killed in Sierra Leone's civil war. Hundreds of thousands became refugees. By January 2002, President Kabbah declared the civil war officially over. In May 2002, Kabbah was re-elected. By 2004, the disarmament process was complete. A UN-backed court began trials for war crimes committed by leaders from both sides. In December 2005, UN peacekeepers left Sierra Leone.

Sierra Leone Today (2002–Present)

Kabbah's Second Term (2002–2007)

Elections were held in May 2002, and President Kabbah was re-elected. The SLPP won most parliamentary seats. In June 2003, the UN ban on the sale of Sierra Leone diamonds ended. By February 2004, over 70,000 former fighters had been helped through a UN program. UN forces handed over security responsibility to Sierra Leone's police and armed forces in September 2004.

The 1999 Lomé Accord called for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to allow victims and perpetrators of human rights violations to share their stories and help with healing. The government and UN also set up the Special Court for Sierra Leone to prosecute war crimes. Both began in 2002. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its report in 2004.

In March 2003, the Special Court issued its first charges. Foday Sankoh, already in custody, was charged, along with other rebel and military leaders. Some died in custody, and others were killed or remain missing. In March 2006, former Liberian President Charles Taylor was transferred to Sierra Leone for prosecution by the Special Court.

Koroma's Government (2007–2018)

In August 2007, Sierra Leone held presidential and parliamentary elections. They were considered fair. No presidential candidate won more than 50% in the first round, so a run-off election was held in September. Ernest Bai Koroma, the candidate of the APC, was elected president. In his inauguration speech, President Koroma promised to fight corruption.

In 2014, the country was greatly affected by the 2014 Ebola virus epidemic in Sierra Leone.

Julius Maada Bio's Presidency (2018–Present)

In 2018, Sierra Leone held another general election. President Koroma could not seek re-election as he had served his maximum two terms. The presidential election went to a second round, where Julius Maada Bio of the SLPP was elected with 51% of the vote. On April 4, 2018, Julius Maada Bio was sworn in as Sierra Leone’s new president.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Sierra Leona para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Sierra Leona para niños

- History of Africa

- History of West Africa

- Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

- List of colonial heads of Sierra Leone

- List of Governors-General of Sierra Leone

- List of heads of government of Sierra Leone

- President of Sierra Leone

- Politics of Sierra Leone

- Freetown history and timeline

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |