History of UK immigration control facts for kids

Before 1905, the United Kingdom had some ways to keep track of people visiting from other countries. However, the modern system for controlling who enters the UK, like we know it today, really started in 1905. There was an old law called the Aliens Act 1793 that lasted until 1836. But after that, until 1905, there were almost no rules about who could come in, except for a very loose system of registering when you arrived.

For information on how rules are enforced *inside* the UK, you can look at UK immigration enforcement.

Contents

- How UK Border Control Began

- After the War: Commonwealth Immigration (1945–1961)

- New Rules After the Empire (1962–1968)

- New Laws and Joining Europe (1968–1978)

- New Visa Rules and Challenges (1979–1989)

- The Rise of Asylum Seekers (1990–1997)

- Expansion and Modernization (1997–2001)

- Asylum Numbers Fall and New Strategies (2002–2005)

- New Agencies (2007–2008)

- Recent Policies (2010–Present)

How UK Border Control Began

The 1905 Aliens Act: New Rules for Visitors

The story of modern UK immigration control really begins in the late 1800s. People were talking a lot about the number of Jewish people from Eastern Europe coming to the UK. There were also worries about foreign criminals in prisons, the cost of helping poor people, and concerns about health and housing.

Many Russian and Polish Jewish people arrived in London's East End. They were escaping difficult situations in the Russian Empire. In 1898, a government report mentioned a "stream of Russian and Polish immigration" that was "increasing year by year." People were especially worried about overcrowding in East London.

This led to a new law called the Aliens Act 1905. It was the first law to say that some visitors were "undesirable." This meant that entering the UK was no longer automatic; it became a choice made by the authorities.

Under this Act, people could be stopped from entering if they:

- Couldn't show they had enough money to support themselves and their family.

- Were mentally ill or sick, and might need public help.

- Had been found guilty of a crime in another country (unless it was a political crime).

- Had already been ordered to leave the UK.

People who were refused entry could appeal to special Immigration Boards. New officers, called Aliens Inspectors (the first Immigration Officers), were quickly hired. Their main job was to check if travelers had money or a job offer. This usually happened on ships or in special "receiving houses" on land.

World War I: Stricter Controls (1914–1918)

A big change happened in 1914. From this point on, everyone entering the UK had to show proof of their identity. The 1914 Aliens Registration Act was passed very quickly, just before the First World War. It allowed much stricter controls. For example, foreigners over 16 had to register with the police.

The 1905 Act was still technically in place, but the 1914 Act's rules were much tougher. The Home Secretary (a government minister) could now stop people from entering or deport them if it was "good for the public." Immigration officers were renamed "Aliens Officers."

To track people, officers started stamping passports with red ink on arrival and black ink on departure. In 1915, a new rule said that foreigners could only land if they had a passport with a photo, issued recently. Before this, passports didn't have photos or stamps.

Officers also had to collect ration documents from people leaving the UK. A "Traffic Index" was created in 1916. This system matched arrival and departure cards to see if people followed their entry rules. This simple system was used until 1998. By 1920, there were 160 Aliens' Officers.

Immigration Rules in the 1920s and 1930s

The Aliens Order 1920 was another important rule. It came out after World War I, when many people were unemployed. It said that all foreigners looking for work or a place to live had to register with the police. This rule gave the Home Secretary a lot of power.

It also said that no foreigner could land without an immigration officer's permission, usually shown by a passport stamp. Officers could add conditions to a person's stay, refuse entry to those who couldn't support themselves, or those who were sick or had committed crimes abroad. It also linked immigration control to the job market for the first time.

Air travel started to become more common in the 1920s. An immigration officer was appointed to handle passengers at London's main airport in Croydon. By 1937, about 37,000 people arrived by air, but this was still much less than the nearly 500,000 arriving by sea.

The 1930s saw more and more refugees arriving from Europe, fleeing Nazi Germany. The number of refugees grew from almost zero in 1930 to 11,000 in 1938. After 1936, people also fled the Spanish Civil War. The UK generally allowed refugees to stay if they could support themselves or had someone to support them. The Immigration Service worked with Jewish support groups to help.

In 1938, the UK Parliament agreed to let up to 15,000 unaccompanied children enter Britain. These children were refugees from the Nazis. Almost 10,000 children, mostly from Germany, were saved by Britain in what was called the Kindertransport.

Large ships like the RMS Queen Mary brought many passengers. To clear them quickly, immigration officers sometimes traveled on the ships or checked passengers in Cherbourg before they even reached the UK.

World War II: Wartime Immigration Control (1939–1945)

War brought new emergency powers. The Immigration Service had to screen refugees, enforce rules for exit permits, and send some enemy foreigners back home. Because Ireland was neutral, new controls were needed between the UK and Ireland. Many immigration officers worked to control Irish workers coming to help the war economy.

Croydon Airport became a fighter base, and passenger flights moved to Shoreham. The Dunkirk evacuation brought many rescued troops and refugees. These people had to be screened to make sure no enemy agents entered the country. Immigration Service staff interviewed refugees at special centers, like the Royal Victoria Patriotic School in London.

As fewer passengers traveled through Channel ports, border control focused on merchant ships. Many staff moved to Scottish ports, Bristol, and northern English ports. In Scotland, large ships brought up to 15,000 troops at a time. Scottish immigration officers also covered airports that were part of dangerous routes to Stockholm. They sometimes met escaped resistance fighters arriving in the Shetland Islands.

After the War: Commonwealth Immigration (1945–1961)

It took time to get normal controls back after the war. Dover was fully staffed again, and Croydon airport reopened. Southampton saw many passenger liners return. A report suggested that air passengers should be separated into arrival and departure areas.

In 1946, Heathrow Airport became London's main passenger airport. It was still a time when many displaced people were returning home. Shipping companies offered cheap fares to the UK for their return journeys. The first ship to arrive with many migrant workers was the MV Ormonde in 1947. However, the arrival of the HMT Empire Windrush in 1948 got much more attention. It brought about 500 passengers and many stowaways.

After the war, the Polish Resettlement Act 1947 allowed 200,000 Polish citizens to stay in the UK. By 1952, wartime travel restrictions between the UK and Ireland were removed, creating a Common Travel Area that still exists today.

The 1953 Aliens Order updated the rules. The 1950s brought special challenges, like many visitors for the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. Despite more travelers, very few people were stopped from entering. In 1953, only 11 people were held in immigration detention in the whole UK.

The situation for refugees was also reviewed. This led to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, which helped define how refugees should be treated. The UK dealt with waves of refugees after the Suez Crisis and Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Between November and December 1956, 4,221 refugees arrived at Dover. The Immigration Service, with fewer than 400 staff, was very busy.

In 1959, for the first time, more passengers arrived by air than by sea.

From the mid-1950s, employers started to recruit workers directly from the West Indies because of a shortage of workers. Many Indian migrant workers also arrived, especially Sikhs from Punjab. Before and after the 1962 Act, the number of family members joining relatives in Britain almost tripled. Families tried to arrive before new, stricter laws came into effect. Total immigration from "New" Commonwealth countries grew from 21,550 in 1959 to 125,400 in 1961.

By 1960, the government was already thinking about laws to control immigration from Commonwealth countries. A government committee discussed how to create a law that wouldn't seem racist, even though it was aimed at "coloured territories." They decided to focus on potential housing shortages as a reason for the new law.

New Rules After the Empire (1962–1968)

The Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 was passed because of growing public concern about immigration from the declining British Empire. West Indian immigration had grown steadily since the war. There were similar public worries to those that led to the 1905 Act. It became clear that the shared citizenship status within the Commonwealth was no longer practical as more people traveled.

The new Act was seen as very strict by some. Preparations for the Act included hiring more staff, bringing the Immigration Service to 500 officers by July 1962.

Commonwealth governments had warned that the new rules would lead to fake documents, and they were right. The 1960s saw a rise in "bogus students" and fake colleges. People would pay criminals for travel, fake documents, and illegal work. Other tricks included fake marriages and birth certificates to bring "children" into the UK who were actually too old.

The Immigration Branch struggled to fight these abuses. There was no formal system to catch illegal migrants until the 1970s.

The quality of Visas issued abroad in Commonwealth countries also became a concern. At first, these were accepted easily. But by 1965, officers were told to impose conditions more often and refuse people who had clearly used false information to get their visas.

Enoch Powell's famous "Rivers of Blood speech" in 1968 changed political discussions about immigration. Some Heathrow immigration officers supported tougher controls, which caused problems for them as civil servants.

In 1968, immigration officers at Heathrow caught James Earl Ray, the murderer of Martin Luther King Jr., trying to travel with a fake passport.

New Laws and Joining Europe (1968–1978)

The Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968 was quickly introduced because Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania became independent. These countries had many people of Indian origin, some of whom had been brought there by Britain. Many of them had UK and Colonies citizenship.

The possibility of many people coming to the UK caused alarm. The new Act said that British subjects could only enter freely if they, or a parent or grandparent, were born, adopted, or naturalized in the UK. This meant that having a British passport from a High Commission abroad no longer guaranteed free entry. A new system with strict limits was introduced for others.

This 1968 Act deliberately favored white Commonwealth citizens who were more likely to have British family roots. Government papers released later showed this was the intention.

By the late 1960s, holding immigration offenders in prison became difficult as numbers grew. A special facility, the Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre, opened near Heathrow.

By the end of the 1960s, immigration laws were too complicated. Everyone agreed a new, clear Immigration Act was needed. In 1972, the Immigration and Nationality Department moved to Lunar House in Croydon. The Immigration Branch at ports was renamed the Immigration Service.

The Immigration Act 1971 gave "right of abode" (the right to live in the UK) to people it called "patrials." These included:

- UK and Colonies citizens born, adopted, or naturalized in the UK.

- UK and Colonies citizens whose parent or grandparent had that citizenship.

- UK and Colonies citizens who had lived in the UK for five years.

- Commonwealth citizens whose parent or grandparent was born in the UK.

- Commonwealth women married to a "patrial" man.

The Act replaced employment vouchers with Work permits, which only allowed temporary stays. Commonwealth citizens who had lived in the UK for five years by January 1, 1973, could also register for the right to live there. Others would be subject to immigration controls.

On the same day, January 1, 1973, the UK joined the European Economic Community (EEC). This meant that while restrictions were placed on Commonwealth citizens, a new privilege was created for European nationals. Membership in the EEC (now the European Union) meant workers could move freely between member states. This was a big change, shifting focus from a diverse group of nations to mainly European ones.

Despite the new laws, the number of Commonwealth citizens settling in the UK still caused political worry. The old paper system for tracking arrivals and departures was replaced by a new computer system (INDECS) in 1979, but it had problems.

New Visa Rules and Challenges (1979–1989)

The government in 1979 introduced more laws, like the British Nationality Act 1981, which made citizenship rules stricter. There were concerns about foreign spouses joining UK partners, especially from the Indian subcontinent. Some people were using marriage to get around the rules. It was hard for immigration officers to tell the difference between real marriages and those arranged just for immigration.

In 1983, new rules required people to prove that the main reason for their marriage was not immigration.

Throughout the 1980s, the government tried to show that immigration numbers were under control. The focus was on how many people were settling in the UK.

By 1986, there was pressure for new visa requirements for some countries. On September 1, 1986, new visa rules were announced for India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, and Ghana. This caused a rush at Heathrow Airport, with hundreds of people waiting to be processed. This further limited entry from Africa and Asia, favoring white EU nations.

A floating detention center called the Earl William was used to hold immigrants. However, in 1987, a strong storm broke its moorings, and it ran aground. This ended the idea of using floating detention centers.

The 1987 Carriers Liability Act made transport companies more responsible for checking passengers' documents. They could be fined £1000 for each passenger without proper papers. This fine later doubled. Despite these fines, the number of people entering illegally continued to rise.

New terminals opened at Gatwick in 1988. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 opened up new travel routes from Eastern Europe. Visa controls were applied to these countries in 1992.

The Rise of Asylum Seekers (1990–1997)

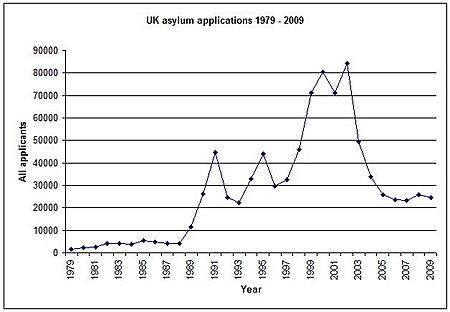

Before 1979, there were no separate statistics for asylum seekers. In 1973, only 34 people were granted refugee status. Most refugees were people fleeing persecution from behind the Iron Curtain.

In 1979, there were 1,563 asylum applications. By 1988, this rose to 3,998. But in 1989, numbers jumped sharply to 11,640, and by 1991, they reached 44,840. This big increase was due to many factors, including cheaper air travel and support groups in the UK.

Only a small number of applicants (5% in 1994) were granted full refugee status. More were given "Exceptional Leave" (later "Discretionary Leave") due to other reasons, like family ties.

The high refusal rates showed that many applicants were seeking economic migration rather than truly fearing persecution. The reasons for the increase included easier travel, existing communities in the UK, job opportunities, and access to legal aid and benefits.

The system for handling asylum applications became overwhelmed, leading to a backlog. Delays meant some applicants eventually got permission to stay just because their cases took so long. This encouraged more people to apply, even if their claims weren't strong.

Between 1995 and 2000, a new problem was asylum seekers entering through the Channel Tunnel. About 700 people a month arrived at Waterloo station. Later, controls were set up at both ends of the tunnel. British officers worked in France, and French officers worked in the UK.

A new team was created in Dover in 1994 to fight the growing problem of people smuggling. This team, the Facilitation Support Unit (FSU), worked with the police. They became experts at prosecuting those who smuggled illegal entrants.

Identifying asylum seekers was important, especially for those whose applications were refused. Without proof of identity, nationality, or how they arrived, it was hard to remove them. Fingerprinting asylum seekers became a key part of this process. Legal powers to fingerprint were given in the 1993 Asylum and Immigration Act.

In 1983, there were only about 180 places for immigration detention, mostly at London airports. These were for short stays. By 1987, more space was needed. The opening of Campsfield House Detention Centre in 1993 added 200 spaces. By 1995, 381 people were in detention centers, and 508 were in prisons.

The cost of detention grew from £7.76 million in 1993/94 to £17.8 million by 1996/97. Tinsley House, opened in 1996, was the first purpose-built immigration detention center.

Expansion and Modernization (1997–2001)

Fairer, Faster, Firmer

In 1998, the government released a plan called "Fairer, faster and firmer." It promised to expand detention centers. This led to new centers like Oakington, Yarlswood, and Dungavel, and an expansion of Harmondsworth. This increased the total detention capacity to about 2,800 by 2005.

This expansion was needed to control people who had been refused entry or whose asylum claims had failed. Removing failed asylum seekers became a top priority. However, there were many challenges, like new applications, appeals, and problems getting travel documents. Keeping people in control during this process was seen as essential.

A sign of modernization was when the Immigration and Nationality Department (IND) published its instructions online in 1998. The "Fairer, faster, firmer" document also highlighted the success of Airline Liaison Officers (ALOs). These officers worked abroad to stop people without proper documents from even boarding flights to the UK. In 1998, ALOs stopped 2,095 passengers with suspicious documents. By 2001, 57 ALOs were working abroad.

Another change was to make it easier and faster to give people permission to enter the UK. This included allowing advance clearance for low-risk groups like tour parties. Permission could be given in writing, by fax, electronically, or verbally. This aimed to speed up passenger flows and use data to identify criminals.

Plans were also made to improve intelligence gathering, based on the police's National Intelligence Model. There were ambitious plans to train immigration officers to make arrests and conduct searches, so they would rely less on the police.

IND Casework Programme

In 1995, IND started a project to develop a new computer system. This project aimed to create a "paperless" office where cases, especially asylum cases, would be handled electronically.

The system was delayed, but an interim computer network was rolled out in 1998. Old casework teams were disbanded, assuming their work would be absorbed by new multi-skilled teams. This caused problems, and the system almost stopped working. The infrastructure that supported thousands of inquiries was damaged. In early 2001, the IT company admitted they couldn't deliver the system. This had a very negative impact on IND.

Home Affairs Committee Report (January 2001)

By 2000, asylum claims reached a new high of 76,040. In February 2000, a parliamentary committee began an inquiry into the rise in asylum claims. They visited a center in France and saw many people waiting to try and enter the UK secretly.

A terrible event happened on June 19, 2000, when 58 Chinese people were found dead in a sealed lorry at Dover. This brought new attention to people trafficking, showing it was organized crime. The committee discussed what made Britain an attractive destination for asylum seekers.

Another event in February 2000 involved nine Afghan nationals who hijacked a plane to Stansted Airport. They and 79 passengers claimed asylum. This case highlighted the Home Office's limited powers. A court later ruled that the hijackers could not be sent back to Afghanistan because their lives would be in danger.

The committee noted that staffing in Immigration Service operational areas had been frozen or reduced between 1995 and 2000. They welcomed plans to increase staff numbers. Indeed, staff numbers in IND rose from 5,000 in 1997 to 11,000 by 2003.

The report recommended combining existing border control agencies into a single force.

Asylum Numbers Fall and New Strategies (2002–2005)

Secure Borders, Safe Haven

In 2002, the Immigration Service Ports Directorate had its highest number of refusals at the border ever: 50,362. This number later fell due to more visas being issued abroad and better screening before entry.

In February 2002, the government published a plan called "Secure Borders, Safe Haven." It continued the modernization policies, outlining plans for more electronic controls like iris recognition and heartbeat sensors to detect hidden illegal entrants. These technologies would also speed up checks for frequent travelers.

The number of new asylum seekers peaked in 2002 at 84,130. The document also discussed how to balance controlling migration with promoting cultural acceptance and social unity.

It promoted "managed immigration" to allow more people to enter legally, especially for work. It also aimed for tougher rules to prevent illegal work. The idea was that migration was good for the economy.

The plan aimed to reduce asylum applications by making it harder for those who didn't claim asylum immediately to get support. It also encouraged legal immigration by relaxing rules for workers. This would test if most asylum applicants were actually economic migrants.

Rules for "working holidays" for young people were relaxed. A new "Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme" was introduced, allowing workers to stay for up to six months without bringing family. The work permit scheme was expanded for medium-skilled workers.

These changes were introduced by the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. A controversial part was cutting off support for some asylum seekers. This was challenged and later ruled to be against human rights.

Despite some setbacks, the number of asylum seekers began to fall. This was due to better handling of cases, faster removals, new appeal rules, and the work of Airline Liaison Officers (ALOs) who stopped undocumented passengers abroad.

New IT tools were introduced, including heartbeat technology and X-ray scanners to detect hidden people in vehicles. In 2003, 3,482 hidden entrants were found; by 2005, this fell to 1,588. More effort was put into getting information from new asylum seekers about smugglers. In 2005, iris screening was tested at ports.

Prime Minister Tony Blair set a goal in 2004: by 2006, the number of failed asylum seekers removed from the UK should be more than the number of new applications. This was called the "Tipping The Balance" target.

Protecting Children

Immigration staff always saw child protection as a high priority. In 2003, a new project called "Operation Paladin Child" was launched at Heathrow Airport. It involved the police, Immigration Service, and other agencies to monitor unaccompanied children arriving. Social services assessed children who met certain criteria.

Between August and November 2003, 1,738 unaccompanied children arrived from non-EU countries. Most were traveling for education or holidays, but some were at risk. The Immigration Service at Heathrow developed special facilities and training to identify children at risk. By 2006, 495 immigration officers were trained in interviewing children.

EU Expansion and Government Changes

In 2004, ten new countries joined the EU, including Poland, Czech Republic, and Hungary. This continued the shift towards free movement mainly within Europe. The government expected 15,000 new workers, but by 2006, about 430,000 had registered for work, with 70% from Poland.

There were concerns about allowing unlimited access to Romania and Bulgaria when they joined in 2007. The Home Office had fast-tracked visa applications for these countries earlier, and it was found that checks were sometimes skipped. This led to concerns about the system's reliability.

The impact on the Immigration Service was not just the new arrivals, but also the opportunities for fraud using their national documents. More migrants from neighboring countries used fake "accession" documents to enter the UK.

Controlling Our Borders: The 2005 Plan

The 2005 plan, "Controlling Our Borders," outlined a new "e-Borders" program. This was a very ambitious project to connect different agencies like the Immigration Service, Police, Customs, and Security Services.

The e-Borders system would collect arrival and departure information electronically from airlines. Passenger details would be checked against watchlists before boarding flights. This would give a clearer picture of people's movements and help agencies target their work.

The plan also included two other main strategies. The "Points Based System" for visas was planned for 2007. The "New Asylum Model" (NAM) aimed to speed up asylum applications and ensure that caseworkers managed cases from start to finish, including removals.

New Agencies (2007–2008)

Problems in 2006 led to a "re-branding" and the creation of the Border and Immigration Agency on April 1, 2007. This agency was meant to be more accountable. A key change was regionalization, dividing the agency into six regions. Border staff would wear uniforms for the first time.

The Immigration Service stopped existing as a separate entity, but its functions continued under the new Border and Immigration Agency. On July 1, Prime Minister Gordon Brown announced plans to combine Customs, the Border and Immigration Agency, and UKvisas into a single border force.

Recent Policies (2010–Present)

The "Home Office hostile environment policy" began around 2010. This policy aimed to make it harder for people who are in the UK illegally to live, work, or access public services. The goal was to encourage them to leave the country voluntarily.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |