History of the Slavic languages facts for kids

The history of the Slavic languages is a long and fascinating journey that spans over 3000 years! It started around 1500 BC when an ancient language called Proto-Balto-Slavic began to split. Over time, this led to the many Slavic languages we hear today. These languages are spoken in places like Eastern, Central, and Southeastern Europe, and even parts of North Asia and Central Asia.

For about 2000 years, the language stayed pretty much the same. This was the pre-Slavic era. Around 500 AD, it was still one language, often called Proto-Slavic proper. Then came the Common Slavic period (about 500–1000 AD). During this time, small differences started to appear, like different accents or words. But people could still understand each other across the whole Slavic-speaking area.

By 1000 AD, the Slavic language family had clearly split into three main groups: East Slavic, West Slavic, and South Slavic. In the next few centuries (11th to 14th century), these groups broke down further into the languages we know today. Some of these include Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian in the East; Czech, Slovak, and Polish in the West; and Bulgarian, Macedonian, and Serbo-Croatian in the South.

The period from the early centuries AD to about 1000 AD was a time of big changes. The Slavic-speaking area grew very quickly. By the end of this time, most of the main features of modern Slavic languages were already in place. The first written records of Slavic words appeared in Greek documents around the 6th century AD. This was when Slavic tribes first met the Byzantine Empire.

The first full texts were written in the late 9th century AD. This language was called Old Church Slavonic. It was the first Slavic literary language. It was based on the South Slavic dialects spoken near Thessaloniki in Greek Macedonia. These texts were important for spreading Christianity among the Slavs, led by Saints Cyril and Methodius. Because these texts were written during the Common Slavic period, they are very helpful for understanding how the Slavic languages developed.

This article will explore how the Slavic languages changed from around 1000 AD to now. For earlier history, you can look at the articles on Proto-Slavic and history of Proto-Slavic.

Contents

- Where Did Slavic Languages Begin?

- How Slavic Sounds Are Written

- How Slavic Languages Became Different

- How Stress and Tone Changed

- Words Borrowed from Other Languages

- See Also

Where Did Slavic Languages Begin?

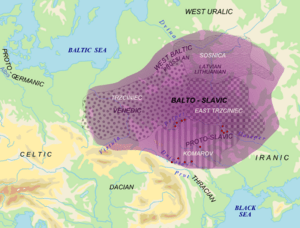

The Proto-Slavic language likely developed in the southern part of the Proto-Balto-Slavic area. We can tell this from old Slavic hydronyms (names of rivers and lakes). The oldest of these names are found between the Carpathian mountains in the west and along the middle Dnieper, Pripet, and upper Dniester rivers in the east.

Scientists who study language changes have estimated that Proto-Balto-Slavic split into its daughter languages between 1300 and 1000 BCE. This suggests that the people of the Komarov and Chernoles cultures might have spoken Proto-Slavic.

From about 500 BCE to 200 CE, groups like the Scythians and Sarmatians expanded their control. Because of this, some words from Eastern Iranian languages, especially about religion and culture, found their way into Slavic. Later, words from Germanic languages also appeared. This happened as East Germanic groups moved into the Vistula and Dnieper river areas.

Around 500 CE, Slavic speakers began to spread out quickly in all directions from a homeland in eastern Poland and western Ukraine. By the 8th century CE, Proto-Slavic was likely spoken in a wide area, from Thessaloniki in the south to Novgorod in the north.

How Slavic Sounds Are Written

When studying old Slavic languages, you might see special marks on letters. These marks help show how words were pronounced, especially their prosody (like stress or tone). They also show other sound differences.

Vowel Letters and Their Meanings

There are two main ways to write vowels in language studies. One system is used for older languages like Indo-European and Balto-Slavic. The other is used for Slavic languages. The main difference is how they show vowel length. In the first system, a line above a letter (like `ā`) means it's a long vowel. In the Slavic system, length is not always clearly marked.

Here's a simple table to show some of these differences:

| Vowel Type | Older System (IE/B-S) | Slavic System |

|---|---|---|

| Short front closed vowel | i | ĭ or ь |

| Short back closed vowel | u | ŭ or ъ |

| Short back open vowel | a | o |

| Long front closed vowel | ī | i |

| Long back closed vowel | ū | y |

| Long front open vowel | ē | ě |

| Long back open vowel | ā | a |

To keep things clear, this article uses the older Balto-Slavic way of writing vowels for sounds up to the Middle Common Slavic period. For later periods, it uses the Slavic way.

Other Marks on Vowels and Consonants

Other marks you might see in Slavic language studies include:

- The haček (like on `č`, `š`, `ž`). This shows a "hushing" sound, similar to `ch` in kitchen, `sh` in mission, or `s` in vision.

- Acute accents (like on `ć`, `ń`, `ś`) or hačeks (like on `ď`, `ň`, `ť`). These show sounds that are more "hissing" or made with the middle of the tongue close to the roof of the mouth.

- The ogonek (like on `ą`, `ę`). This means the vowel is nasal, like the `on` in French bon.

Marks for Stress and Tone

For Middle and Late Common Slavic, special marks show how words were stressed or if they had a certain tone. These are based on the way Serbo-Croatian is written:

- Long rising (`á`): This shows a rising tone on a long vowel.

- Short rising (`à`): This shows a rising tone on a short vowel.

- Long falling (`ȃ`): This shows a falling tone on a long vowel.

- Short falling (`ȁ`): This shows a falling tone on a short vowel.

- Neoacute (`ã`): This shows a special rising accent that happened when the stress moved to an earlier syllable.

How Slavic Languages Became Different

The breakup of Common Slavic was a slow process. Many sound changes spread across the whole area, which was like a dialect continuum (where neighboring dialects are similar, but those far apart are very different). However, some changes were limited to certain areas or had different results.

The end of the Common Slavic period happened when certain weak high vowels, called yers (`ь` and `ъ`), were lost. This created many new closed syllables (syllables ending in a consonant). The rules for which yers were "strong" (and stayed) and which were "weak" (and disappeared) were similar across Slavic languages. But what happened to the remaining sounds was very different.

For example, the consonant groups `*tl` and `*dl` were lost in most Slavic languages, usually becoming `*l`. So, an old word like `*pletlъ` (he wove) became `plel` in many languages.

Also, in many Common Slavic dialects, the sound `*g` changed from a hard `g` sound (like in go) to a softer `gh` sound (like in Dutch gaan). This change is still heard in some modern languages, like Czech, Belarusian, and Ukrainian.

Main Slavic Language Groups

Slavic languages are usually divided into East Slavic, South Slavic, and West Slavic. However, for many comparisons, South Slavic doesn't act as a single group. Bulgarian and Macedonian, for example, are quite different from Serbo-Croatian and Slovene in how their sounds and grammar work. Bulgarian and Macedonian sound more like East Slavic languages. In grammar, they have lost most of the case differences that are still strong in other Slavic languages.

Old Church Slavonic (OCS) is very important for understanding Late Common Slavic (LCS). It helps us reconstruct many features of the language.

Palatalization: Sounds Changing

Palatalization is a sound change where a consonant's pronunciation moves towards the hard palate (the roof of your mouth). At least six different palatalization changes happened in Slavic languages:

- Satemization: This changed very old sounds into `s` and `z` sounds in Balto-Slavic.

- First regressive palatalization: This changed `k`, `g`, `x` (like `ch` in loch) into `č`, `ž`, `š` (like `ch`, `zh`, `sh` in English).

- Second regressive palatalization: This changed `k`, `g`, `x` into `c`, `dz`, `ś` (a soft `s`).

- Progressive palatalization: Similar to the second, but triggered by a preceding sound.

- Iotation: This changed many consonants when they were followed by a `j` sound.

- General palatalization: This made most consonants sound softer when followed by front vowels.

The first palatalization happened very early and is seen in all Balto-Slavic languages. The others are in almost all Slavic languages.

Velar Palatalization Results

The first palatalization (changing `k`, `g`, `x` to `č`, `ž`, `š`) had the same result across all Slavic languages. This shows it happened very early. The second palatalization had more varied results. For example, the `dz` sound often became `z` in most dialects.

Here's how the `k`, `g`, `x` sounds changed in different groups:

| Original | 1st Palatalization | 2nd & Progressive Palatalization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Slavic | k | g | x | k | g | x | |

| Common Slavic | č | ž | š | c | dz | ś | |

| East Slavic | č | ž | š | c | z | s | |

| South Slavic | |||||||

| West Slavic | Lechitic | dz | š | ||||

| Other | z | ||||||

Some dialects, especially South Slavic ones, allowed the second palatalization to happen even if a `*v` sound was in between. For example, the old word `*gvaizdā` "star" became `zvezda` in Russian, Slovene, Serbo-Croatian, Bulgarian, and Macedonian. But in Polish and Czech, it became `gwiazda` and `hvězda` because the palatalization didn't happen across the `v`.

Iotation Results

Most cases of iotation (changes caused by a `j` sound) had the same results in all Slavic languages. However, the sounds `*ť` and `*ď` (from older `*tj`, `*gt/kt`, and `*dj`) merged differently in each language. This shows they were still distinct sounds in Proto-Slavic.

Here's how `*ť` and `*ď` changed:

| Proto-Slavic | OCS | Bulg. | Mac. | S-C | Slvn. | Czech | Slvk. | Pol. | Bel. | Ukr. | Rusyn | Russ. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Written | *ť | št | št | ḱ | ć | č | c | c | c | č | č | č | č |

| Written | *ď | žd | žd | ǵ | đ | j | z | dz | dz | ž | ž | ž | ž |

The exact pronunciation of `*ť` and `*ď` in Proto-Slavic is not fully clear. They might have been like very strong `ch` and `j` sounds.

General Palatalization

Towards the end of the Common Slavic period, most consonants became softer (palatalized) when they were followed by front vowels. This happened in most languages, but not in Serbo-Croatian or Slovene. When the weak yers were lost, these new soft sounds became distinct.

Over time, these newly palatalized sounds became harder again (depalatalized) in varying degrees in all Slavic languages. This happened least in Russian and Polish. For example, in Russian, you can still hear the difference between a hard `t` and a soft `t'` (like in t'ma for darkness).

In Czech, most sounds became harder again around the 13th century. However, the Czech sound `ř` (a special `rzh` sound) shows that `*r` followed by a front vowel did not depalatalize. It had already changed into a new sound.

In Polish, similar changes happened. Sounds like `*r'`, `*l'`, `*t'`, `*d'`, `*s'`, `*z'` changed differently from their hard counterparts. For example, `*l'` became a special `ł` sound, while regular `l` became a `w` sound.

In Bulgarian, you only hear distinctly soft consonants before `a`, `o`, `u`.

This general palatalization also caused the sounds `*y` and `*i` to merge. In East Slavic and Polish, they became different versions of the same sound. In Czech, Slovak, and South Slavic, they merged completely.

The Yers: ь and ъ

The two vowels `ь` and `ъ`, called yers, were originally short high vowels. Later in the Proto-Slavic period, a pattern emerged: some yers became "strong" and others "weak." This is known as Havlík's law. A yer was weak if it was at the end of a word or before another strong yer or regular vowel. A yer became strong if it was followed by a weak yer. This created a pattern where every odd yer in a sequence was weak, and every even yer was strong.

For example, the old name `*sъmolьnьskъ` (Smolensk) would have strong yers in bold and weak yers in italics:

- Nominative singular: `*sъmolьnьskъ`

- Genitive singular: `*sъmolьnьska`

After the Common Slavic period, weak yers slowly disappeared. If a front yer `ь` disappeared, it often left the previous consonant sounding softer. Strong yers changed into mid-vowels, but the exact outcome varied in different Slavic languages.

Here's how strong yers changed:

| Proto-Slavic | OCS | Bulg. | Mac. | S-C | Slvn. | Czech | Slvk. | Pol. | USorb | LSorb | Bel. | Russ. | Ukr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| strong *ь | ь | e, ă | e | a | ǝ,a | e | e (a,á,o) | 'e | e | e | 'e | 'e | e |

| strong *ъ | ъ | ă | o | a | ǝ,a | e | o (e,a,á) | e | e | e | o | o | o |

- An apostrophe means the consonant before it is soft.

- In Serbo-Croatian, Slovene, Czech, and Sorbian, the front and back strong yers merged.

Examples of Yer Changes

Let's look at some examples of how words with yers changed:

| "dog" | "day" | "dream" | "moss" | |

| Middle Proto-Slavic | *pьsь̏ ~ *pьsá | *dь̏nь ~ *dь̏ne | *sъnъ̏ ~ *sъná | *mъ̏xъ/mъxъ̏ ~ *mъxá/mъ̏xa |

| Bulgarian | pes ~ pséta, pésove (pl.) | den ~ déna, dni (pl.) | săn ~ sắništa (pl.) | măx ~ mắxa, mắxove (pl.) |

| Serbo-Croatian | pȁs ~ psȁ | dȃn ~ dȃna | sȁn ~ snȁ | mȃh ~ mȁha |

| Slovene | pǝ̀s ~ psà | dȃn ~ dnẹ̑/dnẹ̑va | sǝ̀n ~ snà | mȃh ~ mȃha/mahȗ; mèh ~ méha |

| Russian | p'os (< p'es) ~ psa | d'en' ~ dn'a | son ~ sna | mox ~ mxa/móxa |

| Czech | pes ~ psa | den ~ dne | sen ~ snu | mech ~ mechu |

| Slovak | pes ~ psa | deň ~ dňa | sen ~ sna | mach ~ machu |

| Ukrainian | pes ~ psa | den' ~ dn'a | son ~ snu | moh ~ mohu |

| Polish | pies ~ psa | dzień ~ dnia | sen ~ snu | mech ~ mchu |

Consonant Groups and Extra Vowels

When weak yers disappeared, they created many new and sometimes tricky consonant groups. Sometimes, an "extra" vowel would appear in a word because a yer was strong in one form but weak in another. For example, the word for "dog" was `*pьsъ` (nominative singular) but `*pьsa` (genitive singular). After the yers changed, this led to Czech pes (dog) but psa (of a dog).

Sometimes, deleting weak yers would create awkward consonant groups at the beginning or end of a word. Languages dealt with these in different ways:

- Some languages, like Russian and Polish, just kept the groups.

- Some changed the weak yer into a strong one, breaking up the group. This happened a lot in Serbo-Croatian.

- Some inserted an extra vowel at the beginning of the word.

Liquid Diphthongs: Vowel-Liquid Pairs

Proto-Slavic had gotten rid of most diphthongs (two vowel sounds together). But it still had sequences of a short vowel followed by `*l` or `*r` and another consonant. These were called "liquid diphthongs." These sequences were also changed by the end of the Proto-Slavic period, but differently in each dialect.

Mid Vowels (e and o)

For the mid vowels `*e` and `*o`, the changes were fairly clear.

- South Slavic languages used metathesis: the liquid and vowel swapped places, and the vowels became longer. For example, `*el` became `*lě`.

- East Slavic languages used pleophony: a copy of the vowel was inserted after the liquid consonant. For example, `*ol` became `*olo`.

- West Slavic languages were a mix. Czech and Slovak used metathesis with lengthening. Polish and Sorbian used metathesis but without lengthening. Some northwestern languages kept `*or` without any change.

Here's how `*el`, `*ol`, `*er`, `*or` changed:

| Proto-Slavic | OCS | Bulg. | Mac. | S-C | Slvn. | Czech | Slvk. | Pol. | Kash. | Bel. | Russ. | Ukr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *el | lě | le/lja | le | lije/le/li | le | le | lie | le | le | olo | olo | olo, oli |

| *ol | la | la | la | la | la | la | la | ło | ło | |||

| *er | rě | re/rja | re | rije/re/ri | re | ře | rie | rze | rze | ere | ere | ere |

| *or | ra | ra | ra | ra | ra | ra | ra | ro | ar | oro | oro | oro, ori |

High Vowels

The liquid diphthongs with high vowels (`*i` and `*u`) changed in more varied ways. In some West and South Slavic languages, special "syllabic sonorants" appeared (like `r` or `l` acting as a vowel). East Slavic languages consistently had vowel-consonant sequences.

Nasal Vowels: ę and ǫ

Nasal vowels (like `ę` and `ǫ`) were kept in most Slavic dialects at first. But they soon changed further. Today, nasality is still found in modern Polish and some dialects of Slovene and Bulgarian/Macedonian. In other Slavic languages, the nasal vowels lost their nasality and merged with other vowels.

Here's how `*ę` and `*ǫ` changed:

| Proto-Slavic | OCS | Bulg. | Mac. | S-C | Slvn. | Czech | Slvk. | Pol. | Bel. | Russ. | Ukr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *ę | ę | e | ja, e | e | ẹ̄ | a, ě | a, ä | ię | ja | ja | ja |

| *ę̄ | ę̄ | ē | á, í | ia | ią | ||||||

| *ǫ | ǫ | ǎ | ja, a | u | ọ̄ | u | u | ę | u | u | u |

| *ǭ | ǭ | ū | ou | ú | ą |

The Yat Vowel: ě

The sound of `*ě` (called yat) also varied across different dialects. In early Proto-Slavic, `*ě` was mainly different from `*e` by being longer. Later, it became a low-front vowel and then a diphthong (like `ia`). This is still seen as `ia` or `ja` in some Bulgarian and Polish contexts. But in most areas, it became `ie`. This `ie` then usually went in one of three directions:

- Stayed as a diphthong.

- Simplified to `e`.

- Simplified to `i`.

All three possibilities are found in the Serbo-Croatian area, known as the ijekavian, ekavian, and ikavian dialects. The ijekavian dialect is the basis for most literary Serbo-Croatian.

In Czech, the `*ě` sound is sometimes still written `ě`, but it's pronounced `je` after certain consonants, or simply `e` in other cases.

In Old Russian, `*ě` simplified to `e`. Later, this `e` sound (when stressed and not followed by a soft consonant) changed to `yo` (like in lyod for 'ice'). In Ukrainian, `*ě` simplified to `i`.

Here's how `*ě` developed in various languages:

| Proto-Slavic | OCS | Bulg. | Mac. | S-C | Slvn. | Czech | Slvk. | Pol. | Bel. | Russ. | Ukr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *ě | ě | ja/e | e | (i)je, e, i | е | ě | (i)e | ie, ia | e | e | i |

- In Bulgarian, it's `ja` when stressed and before a hard consonant, otherwise `e`.

- In Macedonian, it's always `e`. The border between Bulgarian and Macedonian `yat` reflexes is an important language line called the jat' border.

- Polish has `ia` before a hard dental consonant, otherwise `ie`.

How Stress and Tone Changed

Modern Slavic languages vary a lot in how they use vowel length, stress, and tone. All these features existed in Common Slavic. Some languages, like Serbo-Croatian, kept them all. Others, like Polish, lost them.

- Tone: Only found in western South Slavic languages (Serbo-Croatian and some Slovene dialects).

- Length: Found in Serbo-Croatian, Slovene, Czech, and Slovak.

- Stress: Found in Serbo-Croatian, East Slavic languages, Bulgarian, and some Kashubian dialects.

The history of Slavic stress and tone is very complex. Middle Common Slavic (MCS) had three types of stressed syllables: long rising, long falling, and short. Later, Late Common Slavic (LCS) developed four types. Many changes happened after that, leading to the different systems we see today.

For example, in East Slavic, Bulgarian, and Macedonian, the pitch accent changed into a stress accent (like in English), and vowel length and tone were lost. In West Slavic, tone and stress were lost, though Polish kept some vowel length differences that show older length distinctions.

Here's an example of how stress changed for some words:

| Accent | Common Slavic | Chakavian | Slovene | Czech | Slovak | Bulgarian | Russian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circumflex | *gôrdъ "town" | grȃd | grȃd "castle" | hrad "castle" | hrad "castle" | grad-ǎ́t "the town" | górod |

| Acute | *pórgъ "doorsill" | prȁg | pràg (gen. prága) | práh (gen. prahu) | prah | prág-ǎt "the doorsill" | poróg |

| Neoacute | *kõrľь "king" | králj | králj | král (gen. krále) | kráľ | králj-at "the king" | koról' |

Words Borrowed from Other Languages

The Slavic languages also have many loanwords (words borrowed from other languages). These came from different tribes and peoples that Proto-Slavic speakers met. Most of these were from other Indo-European languages, especially Germanic (like Gothic and Old High German), Vulgar Latin or early Romance dialects, and Middle Greek. A smaller number came from Eastern Iranian languages (mostly about religion) and Celtic.

Many Greek and Roman cultural words came into Slavic through Gothic. Studies show that Germanic words were borrowed into Proto-Slavic over a long period, in at least four different stages.

Some words might have come from non-Indo-European languages like Turkic and Avar. But it's harder to be sure about these because there isn't much evidence. When Turkic groups like the Volga Bulgars and Khazars took over parts of Ukraine between the 6th and 8th centuries AD, words like kahan ('ruler'), bahatyr ('hero'), and ban ('high rank') might have entered the Common Slavic language.

See Also

- Proto-Slavic

- History of Proto-Slavic

- Proto-Balto-Slavic

- Old Church Slavonic

- Slavic languages

- Balto-Slavic languages

- Proto-Slavic accent

- Slavic liquid metathesis and pleophony

- Outline of Slavic history and culture

- Individual language histories

- Bosnian

- Czech

- Croatian

- Russian

- Belarusian

- Polish

- Bulgarian

- Macedonian

- Serbo-Croatian

- Slovak

- Ukrainian

- Slovene

- Dialects of Serbo-Croatian

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |