History of videotelephony facts for kids

Videotelephony is like having a phone call where you can also see the person you're talking to! It's also called a video call or video conference. This idea started to become real soon after the telephone was invented in 1876. Its story is very much connected to the history of the telephone itself.

Contents

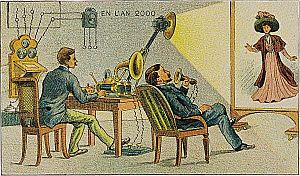

Early Ideas for Video Calls

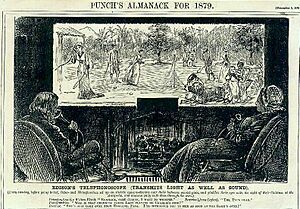

Just two years after the first telephone was patented in the United States in 1876, people started imagining a combined video phone and wide-screen TV. They called it a telephonoscope. This idea appeared in popular magazines and early science fiction books. Artists like George du Maurier even drew pictures of it, imagining it as an invention by Thomas Edison. One drawing was in Punch magazine in 1878.

Another term used in 1878 was "telectroscope." This was used to talk about an invention that people wrongly thought was real and made by Alexander Graham Bell. Articles claimed that a scientist had invented a device that could let people see objects or other people anywhere in the world. This device would let shopkeepers show their goods to customers or allow scholars to see museum collections from far away. Before radio and TV broadcasting existed, people thought these "seeing" devices would work with telephones, creating the idea of a video phone.

Sometimes, there were fake reports about amazing new video phones, even as early as 1880. These reports would pop up every few years. For example, in 1902, a "Dr. Sylvestre" claimed to have invented a powerful and cheap video phone called a "spectograph." Dr. Bell said this supposed invention was just a "fairy tale." He warned people about tricksters who promoted fake inventions for money or fame.

However, Dr. Alexander Graham Bell himself believed that video calls were possible, even if his own work didn't directly lead to them. In 1891, he wrote notes about an "electrical radiophone." He talked about "seeing by electricity" using devices with special parts that could sense images. Bell even predicted that "the day would come when the man at the telephone would be able to see the distant person to whom he was speaking." But the science and materials needed for video technology didn't exist until the mid-1920s. The first video systems were mechanical. More practical, all-electronic video and television didn't appear until 1939. Even then, World War II caused more delays before they became popular.

The word "videophone" became common after 1950. Before that, people used many different terms, like "sight-sound television system" or "visual radio," to describe combining telegraph, telephone, television, and radio technologies.

Early steps towards video phones included machines that sent images over wires, like the wirephoto used by Western Union. AT&T's Bell Labs also developed the teleostereograph, which was like an early fax machine. By 1927, AT&T had created its first mechanical television-videophone called the ikonophone. It showed 18 pictures per second and needed a whole room full of equipment! In a 1927 test, the U.S. Commerce Secretary, Herbert Hoover, spoke to an audience in New York City from Washington, D.C. People in New York could see Hoover, but he couldn't see them.

By 1930, AT&T's "two-way television-telephone" system was being tested. Bell Labs spent years researching it in the 1930s, hoping to use it for both phone calls and entertainment.

Other inventors also showed off their "two-way television-telephone" systems. But they struggled with a big problem: how to make video signals smaller so they could be sent through phone lines. This is called signal compression. Bell Labs eventually found ways to solve this. Sending high-quality color video would need even more advanced technology. After World War II, Bell Labs continued its work, which eventually led to AT&T's Picturephone.

Early Public Video Phone Systems: 1936–1940

In early 1936, Germany launched the first public video phone service called Gegensehn-Fernsprechanlagen (visual telephone system). It was developed by Dr. Georg Schubert. Two closed-circuit televisions were set up in German post offices in Berlin and Leipzig. They were connected by a special cable that stretched about 160 kilometers (100 miles). The system opened on March 1, 1936. The Minister of Posts, Paul von Eltz-Rübenach, made the first call from Berlin to Leipzig's chief mayor.

After the transistor was invented at Bell Labs in 1948, an AT&T engineer predicted:

... whenever a baby is born anywhere in the world, he is given at birth a ... telephone number for life [and] ... a watch-like device with ten little buttons on one side and a screen on the other ... when he wishes to talk with anyone in the world, he will pull out the device and [call] his friend. Then turning the device over, he will hear the voice of his friend and see his face on the screen, in color and in three dimensions. If he does not see and hear him he will know that the friend is dead.

After testing, the system became public. It was later extended to Hamburg, Nuremberg, and Munich. To make a video call, connections had to be swapped on a telephone switchboard. The system eventually used over 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) of special cables. The video phones were placed in large public booths, with two booths in each city. A call between Berlin and Leipzig cost about one-sixth of a British pound sterling, or about one-fifteenth of an average weekly wage.

The video phone equipment in Berlin was designed by the German Post Office Laboratory. Equipment in other German cities was made by Fernseh A.G., partly owned by Baird Television Ltd. from the U.K., who invented the world's first working television. The German system was improved over time, getting better picture quality and switching to an all-electronic camera system. Even though the picture quality was basic by today's standards, people at the time were impressed. Users could even clearly see the hands on wristwatches!

These video phones were offered to the public. People had to visit special post office "video telephone booths" in their cities at the same time. The German post office planned to expand its public video phone network to other cities, but these plans stopped in 1939 when World War II began. The system was closed in 1940, and its expensive cables were used for telegraph messages and broadcast television.

A similar public video phone system was also created in France in the late 1930s.

AT&T Picturephone Mod I: 1964–1970

In the United States, AT&T's Bell Labs did a lot of research and development on video phones. This led to public demonstrations of their "Picturephone" in the 1960s. Their large lab in Manhattan spent years on this research. An early experimental model from 1930 sent video without making it smaller, which was very expensive and not practical.

In the mid-1950s, their lab created another test model that could send still images every two seconds over regular phone lines. The Picturephone's camera captured images, which were then sent over phone lines and shown on a small TV screen. AT&T had shown off its experimental video for telephone service at the 1939 New York World's Fair.

The more advanced Picturephone "Mod I" (Model No. 1) was shown to the public at Disneyland and the 1964 New York World's Fair. The first video call between these two places happened on April 20, 1964. These demonstration units were small, oval-shaped devices on swivel stands, meant for desks. Similar AT&T Picturephone units were also at Expo 67 in Montreal, Canada. People at the fairs could try them out and make video calls to volunteers in other locations.

The first public video phone booths in the United States opened in 1964. AT&T installed their Picturephone "Mod I" in booths in New York's Grand Central Terminal, Washington D.C., and Chicago. This system was the result of decades of research. However, people had to reserve time slots, and the calls were very expensive. A three-minute call from Washington, D.C., to New York cost $16 (about $118 in 2012 dollars), and from New York to Chicago, it was $27 (about $200 in 2012 dollars). Because of the high cost, these booths closed by 1968.

First Video Conferencing Service: 1970

AT&T improved the Picturephone in the late 1960s, creating the "Mod II" (Model No. 2). This model was used to launch the first real video conferencing service. Unlike the earlier system where people had to go to public booths, companies or individuals could now pay to be connected to the system. Then, they could call anyone else in the network from their home or office.

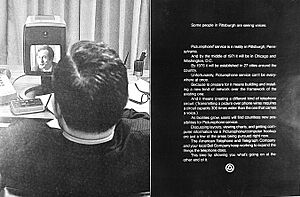

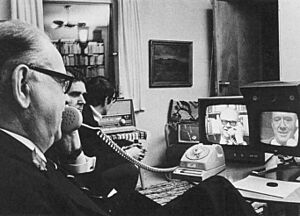

The first official video call happened on June 30, 1970, between Pittsburgh Mayor Peter Flaherty and the CEO of Alcoa, John Harper. The service officially started the next day, July 1, 1970, with 38 Picturephones in eight Pittsburgh companies. Westinghouse Electric Corporation became Bell's biggest Picturephone customer, renting 12 sets. The next year, Picturephone service expanded to Chicago and then to other large East Coast cities.

Service Costs

Besides a $150 installation fee for the first set, companies paid $160 per month (about $947 in 2012 dollars) for the service on the first set. Each extra set cost $50 per month. Thirty minutes of video calling were included with each Picturephone, and extra minutes cost 25 cents. AT&T later lowered the price to $75 per month with forty-five minutes included to try and get more customers.

Picturephone Mod II Details

The Picturephone's video quality was 250 visible lines, updating 30 times per second. The equipment included a speakerphone (hands-free phone) and a box to control the picture. Each Picturephone line used three pairs of regular telephone cables: two for video and one for audio and signals. Amplifiers were placed about every mile (1.6 kilometers) to boost the signal. For longer distances, the signal was turned into digital data and sent over special lines.

AT&T's early Picturephone models did not have color. These Picturephone units had cameras and small TV screens built into them. The cameras were placed above the screens to help people feel like they were making eye contact. Later screens were larger, about six inches (15 cm) square.

- AT&T's advanced Mod II Picturephone (1969)

Commercial Failure

AT&T's Picturephone programs, both the "Mod I" and "Mod II," were a continuation of many years of research. These programs lasted about 15 years and cost over $500 million, but they eventually failed commercially. When it first launched, AT&T expected to have a hundred thousand Picturephones in use by 1975. However, by July 1974, only five Picturephones were being rented in Pittsburgh, and only a few hundred across the entire U.S., mostly in Chicago. Customer numbers peaked at 453 in early 1973. AT&T finally decided that its early Picturephones were "a concept looking for a market."

Later Development (1990s)

AT&T later sold its VideoPhone 2500 to the public from 1992 to 1995. It cost about $1,500 at first, then dropped to $1,000. The VideoPhone 2500 was designed to send low-quality color video over regular phone lines, avoiding the much more expensive special phone lines. It was limited by slow phone line speeds, sending video at only about 11,200 bits per second. This meant it could only send about 10 pictures per second at most, but usually much slower, sometimes as low as one-third of a picture per second. AT&T again had very little success, selling only about 30,000 units, mostly outside the United States.

Even though AT&T's video phone products didn't sell well, they were seen as technical successes. They pushed the boundaries of telecommunications science in many ways. The research at Bell Labs was praised for its amazing results in materials science, advanced telecommunications, and information technologies.

AT&T's research also helped other companies enter the field of videoconferencing. Their video phones also got a lot of attention in science magazines, the news, and popular culture. The image of a futuristic AT&T video phone being used in the science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey became famous.

Other Early Video Phones: 1968–1984

Starting in the late 1960s, several countries tried to compete with AT&T's Picturephone. But these projects needed a lot of research and money, and it was hard to make them work commercially.

France

France's post office had already set up a video phone system similar to Germany's public system from the 1930s. In 1972, Matra, a French defense and electronics company, was one of three French companies trying to develop advanced video phones. Matra planned to give 25 units to France's national telecommunications research center for their own use. They wanted to use it for businesses first, then later for homes. In 1971, it was estimated to cost about £325, with a monthly fee of £3.35.

Studies on how to use video calls were done in France in 1972. The first commercial uses for video phones appeared in 1984. The delay was because there wasn't enough "bandwidth" – meaning, the phone lines couldn't send enough data fast enough for both video and audio. This problem was solved worldwide by creating software called video coding and decoding algorithms, or codecs. These programs made video signals much smaller.

Sweden

In Sweden, the electronics company Ericsson started developing a video phone in the mid-1960s. They planned to sell it to governments, schools, and businesses, but not to regular people, because AT&T hadn't had much success with consumers. Tests were done in Stockholm, including trial calls in banking. In the end, Ericsson decided not to make more of them.

United Kingdom

In 1970, the British General Post Office built 16 demonstration models of its Viewphone, which was similar to AT&T's Picturephone. Their first attempt at a commercial video phone later led to the British Telecom Relate 2000, which went on sale in 1993 for £400-£500 each. The Relate 2000 had a 74 mm (about 3 inch) flip-up color screen that showed about 8 video pictures per second. If the phone line was slow, it could drop to 3-4 pictures per second. Before cheap, high-speed internet was available, people found the video quality to be poor. Images jumped between frames because British phone lines were too slow. British Telecom had expected to sell 10,000 units a year, but actual sales were very low. This second video phone also failed commercially, just like AT&T's VideoPhone 2500.

Digital Video Calls: 1985–1999

This period saw the creation of powerful software that could make video files much smaller. This software, called codecs, eventually led to affordable video calls in the early 2000s.

Video Compression

New ways to make video smaller (called video compression) allowed digital video to be sent over the internet. Before this, video files were too big and needed too much internet speed. For example, a basic video quality (like 480p resolution) without compression would need over 92 megabits per second (Mbps) of internet speed! A common compression method used in video calls is the discrete cosine transform (DCT), developed in 1973. This method was the basis for the first useful video coding standard for online video conferencing, called H.261, which was set in 1988.

Japanese Video Phones

In Japan, the Lumaphone was developed and sold by Mitsubishi in 1985. Mitsubishi Electric of America sold it in 1986 as the Luma LU-1000 for $1,500. It had a small black and white video screen, about 4 cm (1.6 inches) in size, and a camera next to the screen that could be covered for privacy. Even though it was called a "videophone," it worked more like Bell Labs' early image transfer phone from 1956. It sent still images every 3–5 seconds over regular phone lines. It could also be connected to a printer or a regular TV for better viewing.

Mitsubishi also sold a cheaper image phone called the VisiTel LU-500 in 1988 for about $400, aimed at regular people. It had fewer features but a larger black and white screen. Other Japanese electronics companies also sold similar image transfer phones in the late 1980s, including Sony and Panasonic.

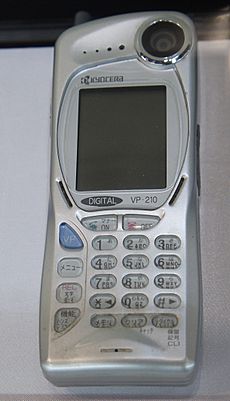

Much later, the Kyocera Corporation in Japan spent two years developing the VP-210 VisualPhone. This was the world's first mobile color video phone that also worked as a camera phone for taking still photos. The camera phone was the same size as other mobile phones at the time. It had a large camera lens and a 5 cm (2 inch) color screen that could show 65,000 colors. It could process two video pictures per second. The 155 gram (5.5 oz.) phone could also take 20 photos and send them by email. It sold for about 40,000 yen (about $325 in 1999).

The VP-210 was released in May 1999. It used its single front-facing camera to send two images per second through Japan's mobile phone network. Even though its video speed was slow and its memory was tiny by today's standards, the phone was seen as "revolutionary" when it came out.

The Kyocera project started because one of their managers, Kazumi Saburi, had a simple idea: "What if we were able to enjoy talking with the intended person watching his/her face on the display?" He believed such a device would make cell phone calls much more convenient and fun.

Engineers at Kyocera faced challenges like fitting the camera inside the phone when electronic parts were still quite large, and increasing the speed of data transfer. After it was released, the mobile video-camera phone was a commercial success. It led to other companies making similar phones.

Video Phone Improvements: After 2000

Video call quality for deaf people greatly improved in the United States in 2003. This happened when Sorenson Media Inc., a company that makes video compression software, developed its VP-100 stand-alone video phone specifically for the deaf community. It was designed to show video on a user's television to make it cheaper to buy. It also had a remote control and powerful video compression software for excellent video quality and easy use with a video relay service (VRS). Good reviews quickly led to its popularity in schools for the deaf and then among the wider deaf community.

With other high-quality video phones from different companies, the availability of high-speed internet, and sponsored video relay services approved by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission in 2002, VRS services for the deaf grew very quickly in the U.S.

|

See also

- History of mobile phones

- History of radio

- History of telecommunication

- History of the telephone

- History of television

- List of video telecommunication services and product brands

- Telepresence

- History of communication

- Timeline of the telephone

- Videotelephony

- Webcam

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |