House of Elzevir facts for kids

The Elzevir family was a famous group of Dutch booksellers, publishers, and printers. They lived in the 17th and early 18th centuries. Their small books, especially the "Elzevirs" series, became very popular. People who loved books, called bibliophiles, really wanted to collect these tiny, well-made books.

The family started in the book business around the 16th century. But we know most about their work starting with Lodewijk Elzevir, also known as Louis. The Elzevir family stopped printing in 1712. Later, in 1880, a different publisher named Elsevier started. They used the Elzevir name and logo for marketing. However, this modern company has no real historical link to the original Elzevir family.

Contents

History of the Elzevir Family

How the Elzevir Name Began

In the past, people spelled names in many ways. The family's name was often "Elsevier" or "Elzevier." Their French books usually kept this spelling. But in English, the name slowly changed to "Elzevir." This became a common way to talk about their books.

The family originally came from Leuven, a city where Louis was born around 1546. Louis worked with books his whole life. In his early years, he was mostly a bookbinder. He moved his family several times, even living in Antwerp for a while. In 1565, he worked for a famous printer named Plantin.

In 1580, Louis finally moved to Leiden. There, he first worked as a bookbinder. Later, he became a bookseller and publisher.

First Books and Key Family Members

For a long time, people thought a book by Eutropius from 1592 was the first Elzevir book. But now we know their first book was Drusii Ebraicarum quaestionum ac responsionum libri duo, printed in 1583. Louis published about 150 books in total. He passed away on February 4, 1617.

Five of his seven sons followed in his footsteps. These were Matthieu (or Matthijs), Louis, Gilles, Joost, and Bonaventura. Among them, Bonaventura Elzevir (1583–1652) became the most famous. He started his own publishing business in 1608. In 1626, he partnered with his nephew, Abraham Elzevir. Abraham was Matthijs's son, born in Leiden in 1592.

In 1617, Isaac Elzevir (1596–1651), Matthijs's second son, was the first in the family to own printing equipment. He left the business in 1626. His equipment then went to Bonaventura and Abraham's partnership. Abraham died on August 14, 1652. Bonaventura passed away about a month later.

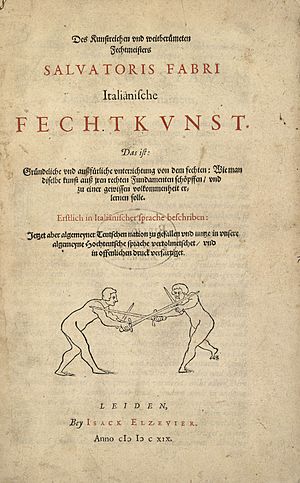

Famous Elzevir Publications

The Elzevir family's fame mostly comes from the books published by Bonaventura and Abraham. Their Greek and Hebrew books were not as good as those from other famous printers. But their small books were truly special. These tiny books were known for their elegant design and clear, neat type. They also used beautiful paper.

Some of their most famous works include:

- Two editions of the New Testament in Greek, published in 1624 and 1633. The 1633 version is more beautiful and sought after.

- The Psalterium Davidis (1653).

- Virgilii opera (1636).

- Terentii comediae (1635).

They also became very famous for two special series:

- The Petites Républiques: This was a collection of French books on history and politics. They were small, 24mo size.

- A series of Latin, French, and Italian classics in small 12mo size.

They are also known for publishing Galileo's last work, Two New Sciences, in 1638. This was a brave move because the Inquisition had forbidden Galileo's writings at that time.

The Petites Républiques Series

Between 1626 and 1649, Bonaventure and Abraham Elzevir published a very popular series called the Respublicae. People often called them the Republics or Petites Républiques. These books were like the first modern travel guides. Each of the thirty-five books in the series gave information about a country. They covered geography, people, economy, and history. The series included countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Near East.

Later Generations of Elzevir Printers

Jean, Abraham's son, was born in 1622. He had been working with his father and uncle in Leiden since 1647. After they died, Daniel, Bonaventure's son (born in 1626), joined him. Their partnership only lasted two years. After that, Jean ran the business alone until he died in 1661.

In 1654, Daniel joined his cousin Louis. This Louis was the third person with that name. He was born in 1604 and had started a printing press in Amsterdam in 1638.

From 1655 to 1666, they published a series of Latin classics. They also printed a large Corpus Juris Civilis in two volumes in 1663. Louis died in 1670, and Daniel in 1680.

Besides Bonaventure, another son of Matthieu, Isaac (born in 1593), also started a printing press in Leiden. He worked there until 1625. But his books did not become as famous.

The last Elzevir printers were Peter and Abraham. Peter was Joost's grandson. He was a bookseller in Utrecht from 1667 to 1675. He printed a few books that were not very important. Abraham was the first Abraham's son. He was the university printer at Leiden from 1681 to 1712.

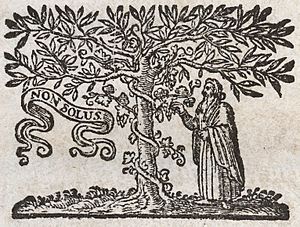

Elzevir Printer's Marks

Some Elzevir books simply say "Apud Elzevirios" or "Ex officina Elseviriana" with the town name. This means "At the Elzevirs" or "From the Elzevir workshop." But most of their books had special symbols, called printer's marks. Four of these marks were used often.

Louis Elzevir, the family founder, usually used the United Provinces's symbol. This was an eagle on a pillar holding seven arrows. Its motto was Concordia res parvae crescunt, meaning "Small things grow by concord."

Around 1620, the Leiden Elzevirs started using a new symbol. It was called le Solitaire, or the Hermit. This mark showed an elm tree, a fruitful vine, and a man alone. Its motto was Non solus (not alone). They also used another mark: a palm tree with the motto, Assurgo pressa (I rise when pressed).

The Elzevirs in Amsterdam used a figure of Minerva as their main symbol. Minerva is the Roman goddess of wisdom. She was shown with an owl, a shield, and an olive tree. Their motto was Ne extra oleas (Not beyond the olives).

The very first books from the Elzevir press had an angel with a hook and a scythe. Other symbols appeared at different times. Sometimes, the Elzevirs did not want to put their name on a book. In these cases, they often used a sphere as a mark. However, just because a 17th-century book has a sphere mark does not mean it was printed by the Elzevirs.

A total of 1608 different works came from the Elzevir presses. There were also many fake copies made by others. Even today, new Elzevir books that were not known before are still being found.

See also

In Spanish: Elzevir para niños

In Spanish: Elzevir para niños

- Books in the Netherlands

- Pierre Marteau is a fake name created by Jean Elzevir. He used it to avoid censorship during his time.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |