Howard Staunton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Howard Staunton |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Full name | Howard Staunton |

| Country | |

| Born | April 1810 |

| Died | 22 June 1874 (aged 64) |

Howard Staunton (born 1810 – died June 22, 1874) was a famous English chess master. Many people thought he was the world's best chess player from 1843 to 1851. He earned this title after winning a big match against the top French player, Saint-Amant, in 1843.

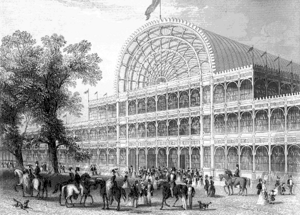

Staunton was also the main person who organized the very first international chess tournament. This event happened in London in 1851. It was held to celebrate the Great Exhibition at Hyde Park, London. These events helped make London a major center for chess around the world. After the tournament, Adolf Anderssen became known as the new strongest player.

Staunton wrote a chess column for the Illustrated London News from 1845 until he died in 1874. He also edited the Chess Player's Chronicle, which was the first important chess magazine in English. He won many matches against other top players in the 1840s. His book, The Chess-Player's Handbook (1847), was a very important guide for chess players for many years.

In 1847, Staunton also started a second career as a Shakespeare expert. Because of his health and his two busy writing jobs, he stopped playing competitive chess after 1851. Later, there were talks about a match between Staunton and the American chess star Paul Morphy. However, the match never happened.

Staunton understood chess strategy, or "positional play," much better than most players of his time. His articles and books were read by many people and helped chess grow. He also helped make two important modern chess openings popular: the Sicilian Defence and the English Opening. Staunton was a strong personality, and his chess writings could sometimes be harsh. But there's no doubt he was a huge figure in the chess world in the mid-1800s. His books and newspaper writings had a big impact worldwide.

Contents

Early Life and Chess Beginnings

Not much is known about Howard Staunton's early life. We don't even know if "Howard Staunton" was his birth name. His birth certificate has never been found, and his parents and birthplace are unknown. He said he was born in 1810.

On July 23, 1849, Staunton married Frances Carpenter Nethersole. She already had eight children from a previous marriage.

In 1849, a man named Nathaniel Cook designed a new chess set. A company called Jaques of London got the rights to make it. Staunton promoted this new set in his Illustrated London News chess column. He said the pieces were easy to tell apart, stable, and looked good. At first, Staunton signed each box label himself. Later, his signature was printed on the labels. He was paid by Jaques for his signature and for promoting the sets. Each set sold earned him a fee. This design became very popular, and "Staunton pattern" sets are still the standard for chess tournaments today.

First Steps in Chess

Staunton was 26 years old when he became very interested in chess. In 1838, he played many games with Captain Evans, who invented the Evans Gambit. He also lost a match against the German chess writer Aaron Alexandre. By 1840, he had improved enough to win a match against the German master H.W. Popert.

From May to December 1840, Staunton edited a chess column for the New Court Gazette. He then became the chess editor for British Miscellany magazine. His chess column grew into its own magazine, the Chess Player's Chronicle. Staunton owned and edited this magazine until the early 1850s.

In early 1843, Staunton won a long series of games against John Cochrane, a strong player. A little later that year, he lost a short match in London against the French player Saint-Amant. Saint-Amant was considered the best French player at that time.

Staunton then challenged Saint-Amant to a longer match in Paris at the Café de la Régence. The prize was £100, which is like £75,000 today. Staunton brought Thomas Worrall and Harry Wilson with him as assistants. This was the first time assistants were known to be used in a chess match. Staunton got a seven-game lead but then struggled to keep it. He eventually won the match 13-8 in December 1843.

Saint-Amant wanted a third match, but Staunton was not eager. He had developed health issues during the second match. After long talks, Staunton went to Paris in October 1844 to start their third match. However, he got pneumonia while traveling and almost died. The match was put off and never happened.

Many chess experts today believe Staunton was the unofficial World Champion after beating Saint-Amant. The official title didn't exist yet.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

In 1845, Staunton started his chess column for the Illustrated London News. This became the most important chess column in the world, and he wrote it for the rest of his life. His articles mostly focused on games played face-to-face. But many also covered "correspondence chess," where players send moves by mail. He also wrote with excitement about promising young players, including Paul Morphy. Staunton wrote over 1,400 weekly articles for the Illustrated London News.

The first chess match played using the electric telegraph happened in 1844. In April 1845, Staunton and Captain Kennedy played two telegraph games against a group in London. Staunton was very interested in this new way to play chess over long distances. He reported on telegraph games in the Illustrated London News. In 1871, he wrote about a telegraph match between Sydney and Adelaide. He calculated that the 74 moves of the longest game had traveled a total of 220,000 miles. That's almost the distance between Earth and the Moon!

In 1847, Staunton published his most famous book, The Chess-Player's Handbook. It's still available today! It had over 300 pages of opening moves and almost 100 pages of endgame analysis. He still found time to play two matches in 1846, easily beating two professional players.

The London 1851 Tournament

Staunton suggested and then led the organization of the first international chess tournament in 1851. He believed the Great Exhibition of 1851 was a perfect chance. It would make it much easier for players from different countries to come and compete.

The tournament committee also set up a "London Provincial Tournament" for other British players. Some of these players were then chosen to play in the International Tournament to make sure there were enough players for the knockout format.

The tournament was a success, but it was a bit disappointing for Staunton himself. In the second round, he was knocked out by Anderssen, who went on to win the whole tournament. In the match for third place, Staunton was just barely beaten by Elijah Williams. Perhaps Staunton tried to do too much by being both a player and the Secretary of the organizing committee. In 1852, Staunton published his book The Chess Tournament. It described all the hard work needed to make the London International Tournament happen. It also included all the games with his comments.

The London Chess Club had some disagreements with Staunton. They organized their own tournament a month later. Many players from Staunton's tournament also played in this one. The result was the same – Anderssen won again.

In the mid-1850s, Staunton got a contract to edit the writings of Shakespeare. This edition was released in parts from 1857 to 1860 and was highly praised.

Later Life and Morphy

While Staunton was busy editing Shakespeare, he received a polite letter from the New Orleans Chess Club. They invited him to their city to play Paul Morphy, who had won the first American Chess Congress. Staunton replied, thanking them for the honor. But he explained that he hadn't played competitively for several years and was working six days a week on his Shakespeare project. So, he couldn't travel across the Atlantic for a match.

He also wrote in the Illustrated London News that he had "been forced, by hard writing work, to stop playing chess, except for an occasional game." He added that if Mr. Morphy wanted to prove himself among European chess players, he should visit the next year. Then, he would find many champions ready to play him in England, France, Germany, and Russia.

When Morphy arrived in England in June 1858, he quickly challenged Staunton to a match. At first, Staunton said no, saying the challenge came too late. Morphy kept trying to get Staunton to play. In early July, Staunton agreed, but only if he had time to practice again. He also needed to make sure it didn't interfere with his Shakespeare contract.

In early August, Morphy asked Staunton when the match could happen. Staunton asked for a delay of a few more weeks. Just before Staunton left London, an old rival accused him of trying to avoid the match. Staunton also received another letter from Morphy pushing him to set a date. Staunton and Morphy met and, after a tense talk, Staunton agreed to play in early November.

However, on October 6, 1858, while in Paris, Morphy wrote an open letter complaining about Staunton's actions. Staunton replied on October 9, explaining his difficulties again. This time, he used them as reasons to cancel the match. On October 23, Staunton published his full reply along with part of Morphy's open letter. The main criticism against Staunton wasn't that he didn't play Morphy. As Lord Lyttleton wrote to Morphy: "Mr. Staunton was right to decline the match... but he should have told you this much earlier... It seems clear... that Mr. Staunton led you to believe he would be ready to play the match soon."

Later Years

Staunton continued writing his chess column in the Illustrated London News until he died in 1874. He welcomed new chess ideas with excitement. In 1860, he published Chess Praxis, which added to his 1847 book. The new book included many of Morphy's games and praised his play.

Five years later, Staunton published Great Schools of England (1865). This book was mainly about the history of major English public schools. But it also shared some modern ideas. For example, he believed that learning works best when students are actively interested. He also thought that physical punishment and older students forcing younger ones to do chores should be stopped.

Most of his later life was spent writing about Shakespeare. This included a photo lithographic copy of the 1600 Much Ado about Nothing in 1864, and of Shakespeare's First Folio in 1866. He also wrote articles about "Unsuspected corruptions of Shakespeare's text" from 1872 until his death. All these works were highly respected at the time.

Howard Staunton died suddenly of heart disease on June 22, 1874. He was at his desk, writing one of these papers. At the same time, he was also working on his last chess book, Chess: theory and practice, which was published after his death in 1876.

A memorial plaque now hangs at his old home at 117 Lansdowne Road, London W11. In 1997, a memorial stone with a chess knight engraved on it was placed over his grave at Kensal Green Cemetery in London. Before that, his grave was unmarked and neglected.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Howard Staunton para niños

In Spanish: Howard Staunton para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |