Paul Morphy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Paul Morphy |

|

|---|---|

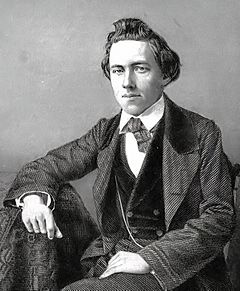

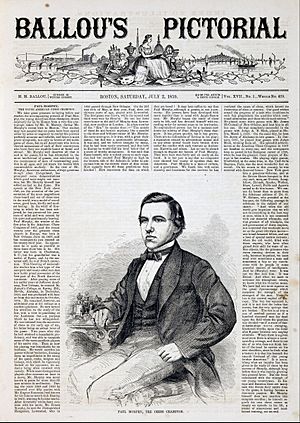

Morphy in Philadelphia, 1859

|

|

| Full name | Paul Charles Morphy |

| Country | United States |

| Born | June 22, 1837 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | July 10, 1884 (aged 47) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

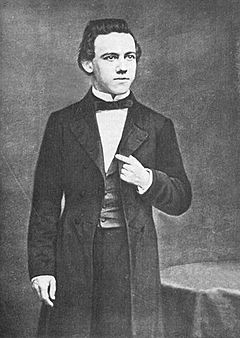

Paul Charles Morphy (born June 22, 1837 – died July 10, 1884) was an amazing American chess player. He lived before there was an official world championship in chess. Many people believed he was the best chess master of his time.

He won the First American Chess Congress tournament in 1857. He beat his opponents by a lot. After that, he traveled to England and France to challenge Europe's top players. He played many games and matches against the best players there, including Adolf Anderssen from Germany. Again, he won almost all his matches easily. When he returned to the United States, he stopped playing competitive chess. He was a chess prodigy, meaning he was super talented at a young age. People called him "The Pride and Sorrow of Chess." This was because he had a brilliant chess career but left the game when he was still young. Experts agree he was far ahead of his time as a chess player.

Contents

Paul Morphy's Life Story

Growing Up

Paul Morphy was born in New Orleans, Louisiana. His family was wealthy and well-known. His father, Alonzo Michael Morphy, was a lawyer. He worked as a state lawmaker and a judge for the Louisiana Supreme Court. Paul's mother, Louise Thérèse Félicité Thelcide Le Carpentier, was a talented musician. She came from a famous French Creole family. Paul grew up in a cultured home where chess and music were popular activities on Sundays.

No one formally taught Paul how to play chess. He learned by watching others, especially his father and uncle. One day, after watching them play a long game, young Paul surprised them. He told them his uncle should have won. His father and uncle didn't know Paul understood the game. They were even more surprised when Paul showed them how his uncle could have won.

Early Chess Wins

By the age of nine, Paul was already one of the best chess players in New Orleans. In 1846, General Winfield Scott visited the city. He was on his way to the Mexican War. He wanted to play chess with a strong local player. General Scott enjoyed chess and thought he was very good. After dinner, Paul Morphy, a small nine-year-old, was brought in as his opponent.

Scott was surprised and thought it was a joke. But he agreed to play after being told Paul was a "chess prodigy." Paul easily won both games. In the second game, he even announced a forced checkmate after only six moves.

Between 1848 and 1849, Paul played against the best players in New Orleans. He played at least fifty games against Eugène Rousseau, one of the strongest players. Paul lost only five of those games.

In 1850, when Paul was twelve, a strong chess master from Hungary named Johann Löwenthal visited New Orleans. Löwenthal had often beaten young, talented players. He thought playing Paul would be a waste of time. But he accepted the game to be polite to Paul's father, who was a judge.

Löwenthal quickly realized Paul was a very strong opponent. Every time Paul made a good move, Löwenthal's eyebrows went up in a funny way. Löwenthal played three games against Paul Morphy. He lost two games and drew one. Some sources say he lost all three.

College and the First American Chess Congress

After 1850, Paul didn't play much chess for a while. He focused on his studies. He graduated from Spring Hill College in Alabama in 1854. He stayed an extra year to study math and philosophy. He earned a master's degree with top honors in 1855.

He then studied law at the University of Louisiana (now Tulane University). He earned his law degree in 1857. People say he memorized the entire Louisiana Civil Code during his studies.

Paul was not old enough to start working as a lawyer yet, so he had free time. He was invited to play in the First American Chess Congress in New York. It was held from October to November 1857. At first, he said no, but his uncle convinced him to play. He beat every opponent. This included James Thompson, Alexander Beaufort Meek, and two strong German masters, Theodor Lichtenhein and Louis Paulsen. Paul was celebrated as the chess champion of the United States. But he seemed calm about his sudden fame. People said he was kind, modest, and polite. In New York, Paul played 261 games. He won 87, drew 8, and lost only 5.

Travels in Europe

At this time, Paul Morphy was not well known in Europe. Even though he was the best in the US, the top chess players lived in Europe. Europeans thought they shouldn't have to travel to the US to play a young, unknown player.

The New Orleans Chess Club decided to challenge the European champion, Howard Staunton, directly. Staunton replied that he couldn't travel to the United States. He said Paul would have to come to Europe if he wanted to play him and other European players.

... If Mr. Morphy—for whose skill we admire greatly—wants to prove himself among Europe's chess knights, he must visit next year. He will find many champions in this country, France, Germany, and Russia, ready to test his skill.

Eventually, Paul went to Europe to play Staunton and other great chess players. Paul tried many times to set up a match with Staunton, but it never happened. Staunton was later criticized for avoiding the match. Staunton was also busy working on his book about Shakespeare. He also played in another chess tournament while Paul was visiting. Staunton later blamed Paul for the match not happening. He even suggested Paul didn't have enough money for the match, which was very unlikely since Paul was popular. Paul also didn't want to play chess for money, possibly due to family reasons.

Paul looked for new opponents and went to France. At the Café de la Régence in Paris, a famous chess spot, Paul easily beat the local chess professional Daniel Harrwitz. In the same place, he showed his amazing skill by playing eight opponents at once while blindfolded. He won all those games.

In Paris, Paul got sick with a stomach illness. Doctors at the time treated him with leeches, which made him lose a lot of blood. Even though he was too weak to stand, Paul insisted on playing a match against the German master Adolf Anderssen. Many people thought Anderssen was Europe's best player. The match happened in December 1858, when Paul was still 21. Despite being sick, Paul won easily, winning seven games, losing two, and drawing two. Anderssen said he was out of practice, but he also admitted Paul was the stronger player. Anderssen even said Paul was the best player ever, even better than the famous French champion La Bourdonnais.

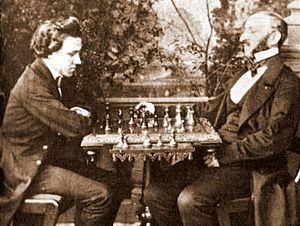

In both England and France, Paul gave many chess shows. He often played and beat eight opponents at a time while blindfolded. Paul also played a famous casual game against the Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard at the Italian Opera House in Paris.

Called World Chess Champion

Paul was only 21 years old and very famous. One evening in Paris, he had a visitor. It was Prince Galitzin. The Prince said he had heard about Paul's "wonderful deeds" all the way in Siberia. He told Paul he must visit Saint Petersburg, Russia, because the chess club there would welcome him warmly.

Paul offered to play a match with Harrwitz, giving him a pawn and move handicap. He even offered to put up money for his opponent, but Harrwitz said no. Paul then said he would not play any more official matches without giving at least those odds.

In Europe, Paul was widely called the world chess champion. In Paris, at a special dinner in his honor in April 1859, a laurel wreath was placed on a statue of Paul. The people there declared him "the best chess player that ever lived." At a similar event in London, Paul was again called "the Champion of the World." He was also invited to meet Queen Victoria. In a game where he played against five masters at once, Paul won two games, drew two, and lost one.

When he returned to America, Paul received more honors. In New York, John Van Buren, the son of President Martin Van Buren, called him "Paul Morphy, Chess Champion of the World." In Boston, at a dinner with famous people, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes toasted "Paul Morphy, the World Chess Champion." Paul's fame led to companies wanting him to promote their products. Newspapers asked him to write chess articles. Even a baseball team was named after him.

Leaving Chess Behind

After coming home in 1859, Paul wanted to start a law career. But he didn't immediately do so. When the American Civil War began in 1861, his brother Edward joined the Confederate army. His mother and sisters moved to Paris. Paul's involvement in the Civil War is not very clear. Some reports say he might have been an officer for a short time. During the war, he lived partly in New Orleans and partly abroad, spending time in Havana and Paris.

After the war ended in 1865, Paul could not successfully build a law practice. His attempts to open a law office failed. When people visited him, they always wanted to talk about chess, not their legal problems. Paul was financially secure because of his family's wealth. He mostly lived a quiet life after that. When fans asked him to return to chess, he refused. In 1883, he met Wilhelm Steinitz (another great chess player) in New Orleans. But Paul refused to talk about chess with him.

Paul believed that chess was only a hobby. He thought it was not a serious job.

Paul had some mental health struggles later in life. His friend Charles Maurian wrote in letters that Paul was "not right mentally." In 1882, his family tried to get him help, but Paul was able to convince them he was fine.

Paul Morphy's Death

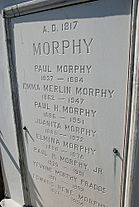

On July 10, 1884, Paul Morphy was found dead in his bathtub in New Orleans. He was 47 years old. The autopsy showed he had a stroke. It was caused by entering cold water after a long walk in the midday heat. Paul was a lifelong Catholic. He was buried in his family's tomb in St. Louis Cemetery #1 in New Orleans. The Morphy family home was sold in 1891. It later became the famous restaurant Brennan's.

Paul Morphy's Chess Style

| This section uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves. |

Paul Morphy is known as a key player of the Romantic school of chess. This style focused on quick, attacking moves. Players often won games in under 30 moves. Paul liked the common chess openings of his time. These included the King's Gambit and Giuoco Piano when he played as White. When he played as Black, he often used the Dutch Defense. The Morphy Defense in the Ruy Lopez opening (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6) is named after him. It is still the most popular way to play that opening.

Paul could play positional chess when he needed to. This means playing for long-term advantages. However, he preferred open games. These games allowed for quick attacks. He thought the Sicilian Defense and 1.d4 openings led to boring games. During his Europe tour, he made sure that at least half of all matches started with 1.e4 e5.

Paul Morphy is seen as the first modern chess player. He understood chess years before his time. He knew what was best to do in a game. In this way, he was like José Capablanca, who was also a child prodigy. Paul played very quickly. He often finished his moves in less than an hour. His opponents sometimes took eight hours or more. Both Löwenthal and Anderssen said he was very hard to beat. He defended well and could win games even from bad positions. He was also very dangerous when he had a good position. Anderssen said that after one bad move against Paul, you might as well give up.

Out of Paul Morphy's 59 serious games (in matches and the 1857 New York tournament), he won 42, drew 9, and lost 8.

Paul Morphy's Legacy

Garry Kasparov, a famous chess champion, said that Paul Morphy understood important chess ideas. These included quickly developing pieces, controlling the center, and opening lines. He realized these things 25 years before Wilhelm Steinitz wrote them down as rules. Kasparov called Paul the "forefather of modern chess." He also called him "the first swallow – the prototype of the strong 20th-century grandmaster."

Bobby Fischer, another great chess player, put Paul Morphy among the top ten players of all time. He called him "perhaps the most accurate player who ever lived." Fischer believed Paul had the talent to beat any player from any time. This would be true if Paul had time to study modern chess ideas.

Reuben Fine, a chess master, had a different view. He said that people who praised Paul too much created a "Morphy myth." He believed that while Paul was great, his games weren't always amazing because his opponents weren't as strong. But even so, Fine said Paul remains one of the "giants of chess history."

Garry Kasparov, Viswanathan Anand, and Max Euwe all agreed that Paul Morphy was far ahead of his time. Euwe called Paul "a chess genius in the most complete sense of the term."

Paul Morphy is often mentioned in Walter Tevis's book The Queen's Gambit. He is the favorite player of the main character, Beth Harmon, who is also a chess prodigy.

Paul Morphy's Game Results

Here are Paul Morphy's results in matches and casual games not played with handicaps:

- + means games won; − means games lost; = means games drawn

| Date | Opponent | Result | Location | Score | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1849−1850 | Eugène Rousseau | Won | New Orleans | c. 45/50 | c. +45−5=0 | casual |

| 1849−1864 | James McConnell | Won | New Orleans | c. 8/8 | +8−0=0 | probably casual |

| 1850 | Johann Löwenthal | Won | New Orleans | 2½/3 | +2−0=1 | casual |

| 1855 | Alexander Beaufort Meek | Won | Mobile, Alabama | 6/6 | +6−0=0 | casual |

| 1855 | A.D. Ayers | Won | Mobile, Alabama | 2/2 | +2−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Alexander Beaufort Meek | Won | New Orleans | 4/4 | +4−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | James Thompson | Won | New York | 3/3 | +3−0=0 | 1st American Chess Congress, elim. |

| 1857 | Alexander Beaufort Meek | Won | New York | 3/3 | +3−0=0 | 1st American Chess Congress, q-final |

| 1857 | Theodor Lichtenhein | Won | New York | 3½/4 | +3−0=1 | 1st American Chess Congress, s-final |

| 1857 | Louis Paulsen | Won | New York | 6/8 | +5−1=2 | 1st American Chess Congress, final |

| 1857 | Louis Paulsen | Won | New York | 3½/4 | +3−0=1 | casual |

| 1857 | Theodor Lichtenhein | Won | New York | 2/3 | +1−0=2 | casual |

| 1857 | Alexander Beaufort Meek | Won | New York | 2/2 | +2−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Daniel Fiske | Won | New York | 3/3 | +3−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Napoleon Marache | Won | New York | 3/3 | +3−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Samuel Calthrop | Won | New York | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Lewis Elkin | Won | New York | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | William James Appleton Fuller | Won | New York | 2/2 | +2−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Hiram Kennicott | Won | New York | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Charles Mead | Won | New York | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Hardman Montgomery | Won | New York | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | David Parry | Won | New York | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Frederick Perrin | Won | New York | 2/3 | +1−0=2 | casual |

| 1857 | Benjamin Raphael | Won | New York | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | James Thompson | Won | New York | 5/5 | +5−0=0 | casual |

| 1857 | George Hammond | Won | New York | 15/16 | +15−1=0 | casual |

| 1857 | John William Schulten | Won | New York | 23/24 | +23−1=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Charles Henry Stanley | Won | New York | 12/13 | +12−1=0 | casual |

| 1857 | Daniel Fiske, W.J.A. Fuller, Frederick Perrin | Lost | Hoboken, New Jersey | 0/1 | +0−1=0 | casual |

| 1858 | Thomas Barnes | Won | London | 19½/27 | +19−7=1 | casual |

| 1858 | Samuel Boden | Won | London | 7½/10 | +6−1=3 | casual |

| 1858 | Henry Edward Bird | Won | London | 10½/12 | +10−1=1 | casual |

| 1858 | Edward Löwe | Won | London | 6/6 | +6−0=0 | casual |

| 1858 | Thomas Hampton | Won | London | 2/2 | +2−0=0 | casual |

| 1858 | George Webb Medley | Won | London | 3/4 | +3−1=0 | casual |

| 1858 | John Owen | Won | London | 4/5 | +4−1=0 | casual |

| 1858 | Johann Löwenthal | Won | London | 10/14 | +9−3=2 | match |

| 1858 | Augustus Mongredien | Won | London | 2/2 | +2−0=0 | casual |

| 1858 | James Kipping | Won | Birmingham | 2/2 | +2−0=0 | casual |

| 1858 | Henri Baucher | Won | Paris | 2/2 | +2−0=0 | casual |

| 1858 | Paul Journoud | Won | Paris | 12/12 | +12−0=0 | casual |

| 1858 | H. Laroche | Won | Paris | 6/7 | +5−0=2 | casual |

| 1858 | M. Chamouillet | Won | Versailles | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1858 | Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant | Won | Paris | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1858 | Jules Arnous de Rivière, Paul Journoud | Lost | Paris | 0/1 | +0−1=0 | casual |

| 1858 | Jules Arnous de Rivière | Won | Paris | 6½/8 | +6−1=1 | casual |

| 1858 | Daniel Harrwitz | Won | Paris | 5½/8 | +5−2=1 | match |

| 1858 | Adolf Anderssen | Won | Paris | 8/11 | +7−2=2 | match |

| 1858 | Adolf Anderssen | Won | Paris | 5/6 | +5−1=0 | casual |

| 1859 | Augustus Mongredien | Won | Paris | 7½/8 | +7−0=1 | match |

| 1859 | Wincenty Budzyński | Won | Paris | 7/7 | +7−0=0 | casual |

| 1859 | A. Bousserolles | Won | Paris | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1859 | F. Schrufer | Won | Paris | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1859 | Johann Löwenthal | Drew | London | 2/4 | +1−1=2 | match |

| 1859 | George Hammond | Won | Boston | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1862 | Félix Sicre | Won | Havana | 2/2 | +2−0=0 | casual |

| 1863 | Augustus Mongredien | Won | Paris | 1/1 | +1−0=0 | casual |

| 1863 | Jules Arnous de Rivière | Won | Paris | 9/12 | +9−3=0 | match |

Famous Games by Paul Morphy

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

- Louis Paulsen vs. Morphy, New York 1857; Paul Morphy sacrificed his queen to create a winning attack on Paulsen's king.

- The "Opera Game"—a casual game against two amateur players. It is one of the clearest and most beautiful attacking games ever. Chess teachers often use it to show how to use tempo (speed), develop pieces, and create threats.

- Morphy vs. Adolf Anderssen, casual game 1858; Paul Morphy won this game with a strong attack.

See also

In Spanish: Paul Morphy para niños

In Spanish: Paul Morphy para niños

- List of chess games

- Morphy Number – This shows how chess players are connected to Paul Morphy.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |