Hugo Kołłątaj facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hugo Kołłątaj |

|

|---|---|

| Deputy Chancellor of the Crown | |

[[File: Portrait by Józef Peszka Portrait by Józef Peszka  |frameless|]] |frameless|]] |

|

| Coat of arms | Kotwica |

| Noble family | Kołłątaj |

| Father | Antoni Kołłątaj |

| Mother | Marianna Mierzeńska |

| Born | 1 April 1750 Dederkały Wielkie, Wołyń |

| Died | 28 February 1812 (aged 61) Warsaw, Duchy of Warsaw |

| Burial | Powązki Cemetery |

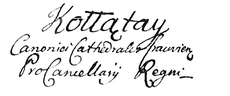

Hugo Stumberg Kołłątaj (pronounced ko-WON-thai, born April 1, 1750 – died February 28, 1812) was a very important Polish reformer and educator. He was a key figure during a time called the Polish Enlightenment. He worked as the Deputy Chancellor of the Crown from 1791 to 1792.

Kołłątaj was a Roman Catholic priest, a social and political activist, a political thinker, a historian, a philosopher, and a polymath (someone who knows a lot about many different subjects).

Contents

Biography

Early life and education

Hugo Kołłątaj was born on April 1, 1750, in Dederkały Wielkie, which is now in Western Ukraine. His family belonged to the Polish nobility, though they were not very rich. Soon after he was born, his family moved to Nieciesławice, where he spent his childhood.

He went to school in Pińczów. Later, he studied at the Kraków Academy, where he focused on law and earned a doctorate degree. Around 1775, he became a priest. He continued his studies in Vienna and Italy, visiting cities like Naples and Rome. In these places, he learned about Enlightenment ideas, which were new ways of thinking about society and government. He is believed to have earned two more doctorates abroad, one in philosophy and one in theology (the study of religion).

Working for education

When Kołłątaj returned to Poland, he became a canon (a type of priest) in Kraków. He also served as a parish priest in two villages. He was very active in the Commission of National Education, which was a government body set up to improve schooling. He also worked with the Society for Elementary Books. He played a big part in creating a national system of schools across Poland.

He spent two years in Warsaw, but then returned to Kraków. There, he worked to improve the Kraków Academy. He was on its board from 1777 and became its rector (head) from 1783 to 1786. His changes to the Academy were very important and set new standards. For example, he made Polish the main language for lectures instead of Latin, which was very unusual for universities in Europe at that time.

His reforms were so new that some of his political opponents tried to get him removed from Kraków in 1781. However, the decision was reversed in 1782, and he continued his work.

Political reforms

Kołłątaj was also very involved in politics. In 1786, he moved to Warsaw and took on a government role in Lithuania. He became a leading figure in the reform movement. He led a group that was considered quite radical, and their opponents called them "Kołłątaj's Forge".

As a leader of the Patriotic Party during the Great Sejm (a special Polish parliament), he wrote down their plans for reform. He published his ideas in works like Several Anonymous Letters to Stanisław Małachowski (1788–1789) and The Political Law of the Polish Nation (1790). In these writings, he suggested changes to the government, including strengthening the king's power, creating a larger national army, getting rid of the "liberum veto" (a rule that allowed any single member of parliament to block a law), introducing taxes for everyone, and giving more rights to townspeople and peasants.

He helped organize a movement for townspeople's rights. He edited a document that asked for reforms, which was given to King Stanisław August during a protest called the Black Procession in 1789.

Kołłątaj was one of the main authors of the Constitution of 3 May 1791, which was a very important document for Poland. He also started a group called the Friends of the Constitution to help make sure the new laws were put into practice. For his work, he received important awards: the Order of Saint Stanislaus in 1786 and the Order of the White Eagle in 1791. From 1791 to 1792, he served as Crown Vice Chancellor, a high government position.

Exile and later life

A war broke out between Poland and Russia in 1792 because of the new 3 May Constitution. Kołłątaj and other royal advisors convinced King Stanisław August to try and make peace with their opponents. The king joined the Targowica Confederation, a group that wanted to undo the Constitution.

However, when the Confederates won in 1792, Kołłątaj had to leave Poland. He went to Leipzig and Dresden. In 1793, he wrote an essay with Ignacy Potocki about how the May 3 Constitution was adopted and then failed.

While in exile, his political ideas became even stronger. He started preparing for a rebellion. In 1794, he took part in the Kościuszko Uprising, a fight for Poland's independence. He helped write important documents for the uprising, like the Uprising Act and the Połaniec Manifesto. He led the Treasury Department of the Supreme National Council and supported the more radical side of the uprising.

After the uprising was defeated in 1794, Kołłątaj was captured and imprisoned by the Austrians until 1802. In 1805, he helped organize the Krzemieniec Lyceum, a school in Volhynia.

In 1807, when the Duchy of Warsaw was created, he was initially part of its government. But soon, his political rivals managed to get him removed. He was then arrested and imprisoned by the Russian authorities until 1808. After his release, he was not allowed to hold public office.

Despite this, he continued to work on plans for rebuilding Poland. He wrote "Remarks on the Present Position of That Part of the Polish Lands that, since the Treaty of Tilsit, have come to be called the Duchy of Warsaw" (1809). In 1809, he became a member of the Warsaw Society of Friends of Learning. From 1809 to 1810, he was again involved with the Kraków Academy, helping it recover after it had been temporarily influenced by German ideas.

Final works and death

In his book The Physico-Moral Order (1811), Kołłątaj tried to create a system of ethics that emphasized that all people are equal. This idea was based on the physiocratic concept of a "physico-moral order."

He was also very interested in natural sciences, especially geology and mineralogy. He wrote A Critical Analysis of Historical Principles regarding the Origins of Humankind, which was published after his death in 1842. In this work, he presented the first Polish ideas about how society changes over time, based on geological concepts. This book is also seen as an important contribution to cultural anthropology (the study of human cultures).

In another work, The State of Education in Poland in the Final Years of the Reign of Augustus III, published after his death in 1841, he argued against the Jesuit control over education. He also provided a study of the history of education.

Hugo Kołłątaj died on February 28, 1812. He was buried in the Powązki Cemetery.

Remembrance

Even though he died somewhat forgotten by people at the time, Kołłątaj later became a major influence on many reformers. Today, he is recognized as one of the most important figures of the Enlightenment in Poland. He is considered "one of the greatest minds of his time."

He is one of the people shown in Jan Matejko's famous 1891 painting, Constitution of May 3, 1791.

Several important schools and institutions in Poland are named after Hugo Kołłątaj, including the Agricultural University of Cracow, which he helped to establish.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hugo Kołłątaj para niños

In Spanish: Hugo Kołłątaj para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |