Huron Cemetery facts for kids

|

Huron Cemetery

|

|

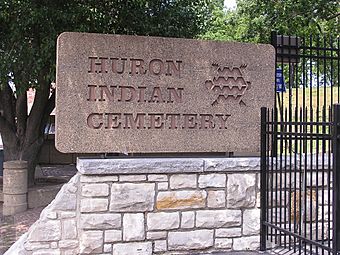

Entrance to the Huron Indian Cemetery in downtown Kansas City, Kansas.

|

|

| Location | Kansas City, KS |

|---|---|

| Area | 2.5 acres (1.0 ha) |

| Built | 1843 |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000335 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | September 3, 1971 |

| Designated NHL | December 23, 2016 |

The Huron Indian Cemetery in Kansas City, Kansas is a very important burial ground. It is also known as Huron Park Cemetery or the Wyandot National Burying Ground. This cemetery was created around 1843. It was established soon after the Wyandot people moved to Kansas from Ohio.

The Wyandot tribe lived in the area for many years. In 1855, many Wyandot people became United States citizens. They accepted individual land plots in Kansas. Most of the Wyandot moved to Oklahoma in 1867. There, they kept their tribal traditions and shared property. As a federally recognized tribe, they had legal control over the Huron Cemetery.

For over 100 years, this cemetery has been a source of debate. The Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma wanted to sell the land. They wanted to use it for new buildings. However, the smaller, unrecognized Wyandot Nation of Kansas wanted to protect it. They wanted to keep it as a sacred burial ground.

The cemetery is located at North 7th Street Trafficway and Minnesota Avenue. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 3, 1971. It is part of the Kansas City, Kansas Historic District. It was also listed on the Register of Historic Kansas Places on July 1, 1977. In December 2016, the cemetery was named a National Historic Landmark.

In the early 1900s, Lyda Conley and her two sisters fought hard to save the cemetery. They lived in Kansas City, Kansas. Many people wanted to build on the land. In 1916, the cemetery got some protection as a national park. This was thanks to Kansas Senator Charles Curtis. But new plans to develop the land kept coming up every ten years or so.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 helped protect the cemetery even more. This law says that descendants of those buried there must be asked for their opinion. They have a say in what happens to cemeteries and gravesites. Wyandot descendants in Kansas strongly supported keeping the cemetery as it was.

In 1998, the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma and the Wyandot Nation of Kansas signed an agreement. They agreed to use the Huron Cemetery only for religious, cultural, or other activities. These activities had to fit with the site's use as a burial ground.

Contents

The Wyandot People's Journey to Kansas

The Wyandot people moved from Ohio to Missouri and Kansas in 1844. They arrived near the Missouri and Kaw rivers in July 1843. They first settled near Westport. Later, the Delaware tribe sold them land in what is now Wyandotte County. They also gave them three sections of land as a sign of friendship.

The Wyandot lived in a low area and many got sick. Survivors buried their dead on a ridge overlooking the Missouri River. This place became known as the Huron Cemetery.

Later that year, the United States gave land in Kansas to the Wyandot. This land included the ridge where the cemetery was. The Wyandot continued to use it as a burial ground.

In 1855, many Wyandot people became U.S. citizens. They agreed to receive individual plots of tribal land. The tribal government was then ended. But the Huron Cemetery remained as shared land. It was used by Wyandot members in Kansas City. Four years later, the Town of Wyandot was formed. The Huron Cemetery was inside its borders. This town later became part of Kansas City.

Quindaro Townsite and the Underground Railroad

In the mid-1850s, the Wyandot also agreed to sell some of their land. This land was used to create the Quindaro Townsite. This town was founded in late 1856. It was a free port-of-entry on the Missouri River. It was started by abolitionists who were against slavery. Quindaro was named after the Wyandot wife of one of the founders.

Buildings were quickly built in the town's business area in 1857. Many settlers came from New England. They wanted to help Kansas become a free state by voting on its status. More homes were built on the ridge above the river.

The Wyandot people at Quindaro and on their own land helped slaves escape. They provided a safe place for slaves on the Underground Railroad. Some Wyandot helped slaves who had crossed the river from Missouri. They helped them travel further north to freedom.

Protecting the Cemetery

After the American Civil War, in 1867, most Wyandot members moved again. This time, they moved to 20,000 acres (81 km²) in Oklahoma. These were members who had not become citizens or who wanted to stay part of the tribe. The Wyandot who stayed in Kansas were called "absentee" or "citizen class."

The Oklahoma nation kept its tribal government. So, its leaders kept legal power over the shared land of the Huron Indian Cemetery.

As Kansas City grew, the Huron Indian Cemetery land became very valuable. This was in the 1890s. Developers wanted to buy the cemetery land. They talked with the legal owners, the leaders of the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma. In 1906, the Wyandotte asked Congress to tell the United States Secretary of the Interior to sell the land.

A Carnegie library, the Brund Hotel, and a Masonic Temple were already built nearby. The money from the sale would go to the Nation in Oklahoma. The plan was to move the remains from Huron Cemetery to the Quindaro Cemetery nearby.

Over the years, the cemetery was often at the center of arguments. Some people wanted to preserve it, while others wanted to develop it. The fight was also between the unrecognized Wyandot Nation of Kansas and the federally recognized Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma. Since the late 1800s, the Oklahoma group was the only one with legal power over the site.

Lyda Conley and her two sisters in Kansas City started a public and legal fight to stop the sale. Other local Wyandot descendants joined them. Women's clubs and similar groups also helped. In 1909, Lyda Conley became the first Native American woman lawyer to argue a case at the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court understood her feelings but did not stop the land sale.

In 1916, Kansas Senator Charles Curtis helped. He was a multi-racial member of the Kaw tribe and later became Vice President. Congress passed a law to protect the Huron Indian Cemetery as a park. The federal government then made an agreement with Kansas City to take care of it.

But over the years, Kansas City and the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma still thought about building on the site. This would mean moving the Wyandot remains. The Wyandot Nation of Kansas was formed in 1959. They have been trying to get federal recognition. They strongly support keeping the cemetery as a historic site.

The cemetery's great location still attracts interest from developers. But because it is so important, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971. It was officially renamed the Wyandot National Burying Ground.

The cemetery is part of the Kansas City, Kansas Historic District. It was also listed on the Register of Historic Kansas Places in 1977. In 1978-1979, the city put in new grave markers.

The Cemetery Today

Experts believe there are more than 400 bodies buried in Huron Indian Cemetery. Some think there might be as many as 800. Only a few of the graves have markers. People were still being buried there in the late 1900s.

Sometimes, there has been vandalism at the cemetery. In 1991, Kansas City put in over 70 new grave markers. They worked with the tribe and archaeologists to replace older ones. The Huron Indian Cemetery is open from morning until evening. The grounds are nice, but the cemetery needs more money to stay well-kept.

In 1994, the chief of the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma thought about putting a gaming casino at Huron Park Cemetery. Gaming (casinos) has become a big way for Native American tribes to make money. But representatives of the Wyandot Nation of Kansas protested. They spoke to their members of Congress.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) said that nothing could happen without talking to many groups. Most importantly, they needed permission from the descendants of those buried there. This is required by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990.

After more than 100 years of disagreement, an agreement was finally signed in 1998. The Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma and the Wyandot Nation of Kansas agreed. They would use the Huron Cemetery only for religious, cultural, or other activities. These activities had to respect the site as a sacred burial ground. Their agreement also said that the Oklahoma nation would not stop the Wyandot Nation of Kansas from trying to get federal recognition. The Kansas group is currently recognized by the state. In 2016, the cemetery was named a National Historic Landmark.