Quindaro Townsite facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Quindaro Townsite

|

|

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Kansas City, KS |

|---|---|

| Built | 1857 |

| NRHP reference No. | 02000547 |

| Added to NRHP | May 22, 2002 |

The Quindaro Townsite was once a busy settlement. Then it became a ghost town, and later an important archaeological site. You can find it near North 27th Street and the Missouri Pacific Railroad tracks in Kansas City, Kansas. This special place was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 22, 2002.

The town was started in 1856 by Wyandots and others. It was meant to be a port for "Free Staters" moving into the Kansas Territory. Construction began in 1857. Quindaro quickly grew, with its population reaching 600 people. Many settlers were supported by the New England Emigrant Aid Company. This group wanted to make Kansas a free territory, without slavery.

Quindaro was one of several towns along the Missouri River. It was founded to help stop slavery from spreading west. People in Quindaro also helped enslaved people escape from Missouri. It was a "station" on the famous Underground Railroad.

After Kansas became a free state, the need for the port lessened. The town's growth slowed down. The economy in Kansas also faced problems at that time.

In 1862, classes started for children of former slaves. By 1865, a group of men started the Quindaro Freedman's School. This school later became Western University. It was the first school for Black students west of the Mississippi River. More former slaves moved to the area, and by the late 1800s, it was mostly an African American community. In the early 1900s, the area became part of Kansas City. Western University closed in 1943.

The town declined sharply during a national economic downturn and the American Civil War. The lower part of the town, where businesses were, was left empty and became overgrown. It was rediscovered during an archaeological study in the late 1980s. This study found many parts of the 1850s town.

The only building or structure left from Western University and Quindaro is a statue of John Brown. John Brown was a famous abolitionist who fought against slavery. In 1978, the John Brown Memorial Plaza was dedicated.

In 2019, the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act named it the Quindaro Townsite National Commemorative Site. This means the National Park Service can help protect the site and teach people about its history.

Contents

History of Quindaro

How Quindaro Started

The Kansas–Nebraska Act opened the Kansas Territory for new settlers. It said that people living there would vote to decide if Kansas would allow slavery or be a free state. The New England Emigrant Aid Company (NEEAC) helped over 1,200 settlers move to Kansas. They hoped to make Kansas a free territory.

People who were against slavery, called Abolitionists and Free-Staters, wanted to create a free-state port. This port would go against the pro-slavery ports like Leavenworth and Kansas City, Missouri. They found a good spot near the Wyandot town, Wyandotte City.

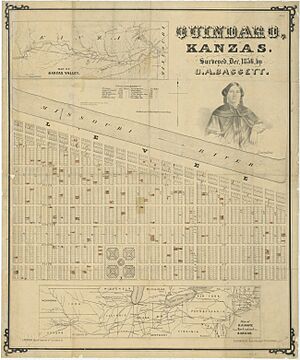

A group called the Quindaro Town Company was formed. Its leaders included Joel Walker, Charles Robinson (who later became governor of Kansas), and Abelard Guthrie. The town was named Quindaro because the company bought land from Nancy Quindaro. She was a Wyandot woman. In the Wyandot language, Quindaro means "bundle of sticks" or "strength through numbers."

Quindaro was one of several small ports on the Missouri River. Planners chose this spot because it had a good natural rock ledge. This made it easy for boats to land. There was also plenty of wood and rock for building.

Building started in January 1857. Soon, the town had many stone houses and businesses. Its sawmill was the biggest in Kansas. The lower part of town, near the river, was for businesses. Most homes were higher up on the bluff. In the first year, 100 buildings were finished. These included hotels, stores, and two churches. Native people living there were not forced to leave. They became part of Quindaro.

A young man named John Morgan Walden came to Quindaro. He started a Free-Soil newspaper called Quindaro Chindowan. Chindowan was a Wyandot word meaning "leader." Walden also helped former slaves. He later became a bishop in the Methodist Church.

Quindaro and the Underground Railroad

After the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854, a western part of the Underground Railroad started in Kansas. Quindaro became a key stop on this route. It offered a new way for enslaved people to escape from Missouri. This was very important before Kansas became a free state in 1861. Quindaro became known as a safe place for fugitive slaves. Later, during the American Civil War, it helped "contraband" (escaped slaves) too.

Clarina Nichols was a writer for the Quindaro Chindowan newspaper. She was a friend of Susan B. Anthony. Clarina Nichols was a very important "Conductor" on the Underground Railroad in Quindaro. She helped many people escape to freedom. She once wrote about a time when a freedom seeker named Caroline came to her house. Fourteen slave hunters were looking for Caroline. Clarina hid Caroline in a secret, empty cistern overnight. As soon as it was safe, Caroline was sent north to freedom.

Why Quindaro Declined

Quindaro's population reached 600 people. But the town quickly faced problems. A nationwide economic depression hit. Also, efforts to bring a railroad to Quindaro failed. During the American Civil War, many young men joined the Union Army. Only a few farming families stayed. The lower part of the town, by the river, was mostly left empty. Later, African American families settled in the upper town on the bluff.

The economy in Kansas also suffered. In 1862, the state government took away Quindaro's town charter. This meant the town corporation stopped operating. It was also hard to get goods from the river up to the town. After the war, the port was not needed as much. The land around Quindaro was limited, which stopped it from growing.

After being abandoned, the old business area became overgrown. Some parts were even covered by earth falling from the bluffs. Historians remember it as a ghost town. In the early 1900s, all of the townsite became part of Kansas City, Kansas.

Western University

Even before the Civil War ended, a man named Eben Blachly started classes in his home in 1862. These classes were for the children of former slaves. Blachly was a Presbyterian. He started the Quindaro Freedman's School, which later became Western University. The school was officially started in 1867. He ran it until he passed away in 1877.

Western University was a historically black university (HBCU). It was located in the upper part of Quindaro. In 1872, the state government added a four-year teaching program. Charles Henry Langston was the principal then. He was a leading Black abolitionist, activist, and educator.

In the early 1900s, Western University became famous for its music program. Music historian Helen Walker-Hill said that Western University was "probably the earliest black school west of the Mississippi." She also said it was "the best black musical training center in the Midwest" for almost 30 years.

In the early 1900s, Western University added many hands-on training programs. It had buildings for livestock and a laundry. Later, a building was added for teaching auto mechanics and repair. The university closed in 1943.

Today, only the statue of John Brown remains. Some early building cornerstones can also be found. Some buildings were lost to fire, and others were torn down. The last three faculty houses were demolished in the late 1900s. One of these houses is now the Old Quindaro Museum. The Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum is nearby. It is in the Vernon Multipurpose Center, which used to be the Quindaro Colored School.

Archaeology and History Projects

An archaeological study in 1987–1988 found the remains of the 1850s townsite. This study was done for a public project. They found the foundations of 20 main buildings, two smaller buildings, three wells, and one cistern. Researchers know other buildings existed from old maps, newspapers, and letters. Because the town was so important, the site is now an archaeological district. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Many public projects have been done to share these discoveries.

In 1993, Kansas State University worked with local groups. They asked students to create ideas for a park at Quindaro. The students presented 13 ideas at a public meeting. These ideas were also shown at the state capitol. While no single plan was chosen, these efforts helped teach people about Quindaro's history.

In 1996, the University of Kansas started an oral history project. Professors interviewed people from the nearby African-American community. They listened to family stories about Quindaro. The history and legends of the settlement lived on in these stories. Because Quindaro existed for a short time, not much was written down. These projects helped find new information.

In December 2007, a grant was given to the Concerned Citizens of Old Quindaro. This grant was for an exhibit called In Unity There is Strength: The African American Experience. The exhibit showed the history of former slaves who escaped to Quindaro. It covered the community's religious, educational, and business life.

In 2018, people involved with Quindaro started working together. These included historians, archaeologists, and activists. They began to solve long-standing issues about how to manage the historic site.

Images for kids