Hwlitsum First Nation facts for kids

The Hwlitsum First Nation is a group of Indigenous people who are the descendants of the Lamalchi people. The Lamalchi changed their name to Hwlitsum when they moved to Hwlitsum (Canoe Pass, British Columbia) in 1892. In the Hul'qumi'num culture, groups are named after where their winter village is located. So, when they moved their winter village, their name changed too. The Hwlitsum speak the Hul'qumi'num language, and their traditional home is in the Southern Gulf Islands. The Hwlitsum were never given official reserves or recognized as a "band" by the government. They are currently working to be recognized as a band government by the governments of British Columbia and Canada.

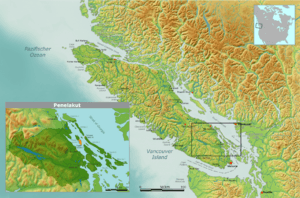

The Hwlitsum are connected to the Lamalchi (also called Lamalcha) peoples who lived on Penelakut Island (which used to be Kuper Island) in the Gulf Islands. The name Hwlitsum refers to Canoe Pass, which is near Steveston in Richmond, British Columbia. It means “People of the Cattails.”

Contents

Amazing Origin Stories

- One story from Penelakut Island tells of two cedar logs that lay on the shore. From these logs, the very first man and woman on the island came to life. These people became the ancestors of the Hul'qumi'num-speaking nations. Other people also came from mountains and hills on Vancouver Island or rose from the sands of Penelakut Island.

- Another story is about two Sqwxwa'mush families, Ah-Thult and Hola-Pult, who built houses on an island. Their houses were in different bays, separated by a rocky point. Ah-Thult's family was not successful at hunting and asked Hola-Pult for advice. Hola-Pult's family had great success hunting. They suggested that maybe Ah-Thult was not pure enough to be visited by the hunting spirit. Ah-Thult left his family to go into the mountains until he felt clean. While there, spirits visited him and showed him how to be a successful hunter. When Ah-Thult returned, Hola-Pult decided to try and steal this hunting ability. But Ah-Thult tricked him into leaving the Island. Hola-Pult and his men were led to Penelakut Island and decided to move there. This became the home for the Lamalchi people, who lived on the land until they moved to Hwlitsum (Canoe Pass).

A Look at Hwlitsum History

In Hul'qumi'num culture, groups of people are known by where their winter village is located. The Lamalchi's winter home was on Penelakut Island at Lamalcha Bay. Before 2010, Penelakut Island was called Kuper Island. The Lamalchi shared Penelakut Island with the Penelakut and Yekaloas peoples. The Lamalchi also had permanent summer villages in Hwlitsum (Canoe Pass). In 1892, the Lamalchi were stopped from returning to their winter home in Lamalcha Bay. So, they spent the winter in Hwlitsum. Following their custom, they changed their name to Hwlitsum at that time.

The Hwlitsum Nation's family history can be traced back to the late 1790s. Old records and maps show that the Lamalchi were living and working on Penelakut Island in the early 1800s.

European explorers had only briefly visited Hul'qumi'num territories by the early 1850s. When Europeans first arrived and when the British claimed control in 1846, the Lamalchi were an independent group within the larger Coast Salish community. The Lamalchi had family and marriage connections to the Lummi Nation, Musqueam Nation, and Katzi Nation. They were also part of the larger Cowichan community. The Lamalchi were one of the smaller groups within the Cowichan people. They had different histories and cultural practices from their neighbors on Penelakut Island. Penelakut Island was shared by the Penelakut, the Yekaloas, and the Lamalchi, who all had their own separate villages.

The Lamalcha Nation was not officially recognized by the British when the border between Canada and the United States was drawn in 1846. The British and United States authorities, who decided to use the 49th parallel as the international border, did not identify the Lamalchi. This mistake meant the Lamalchi were not included in any treaty agreements. Today, the Hwlitsum, who are descendants of the Lamalchi, are working with the Canadian government to fix this missing information in the official records.

Before and during the time of European contact, the Lamalchi were involved in conflicts with other tribes along the coast. Warriors would speak to approaching canoes in Hul'qumi'num. If the people in the canoe did not respond in Hul'qumi'num, they were not allowed to travel in Hul'qumi'num waters.

The Lamalcha/Hwlitsum defended themselves against attacks from the Royal Navy during the time of the Colony of Vancouver Island. After these events, their traditional lands were taken over by other groups who did receive reserves and official status rights. These rights were not given to the Lamalcha.

How the Hwlitsum Are Organized

The Hwlitsum First Nation is their political group. They are currently working to be legally recognized as a band government under the Indian Act. This act is a Canadian law that deals with First Nations. They are also working with the Tsawwassen First Nation on shared interests in the Fraser Estuary. They tried to have their interests included in the Tsawwassen Treaty talks, but that treaty was finished without their concerns being addressed.

In 2007, the Union of BC Indian Chiefs sent a letter to the federal and provincial governments supporting the Hwlitsum's cause. They are part of the BC Treaty Process to gain recognition, but they are still not an officially recognized band government.

Their Language and Travel

The Hwlitsum, as descendants of the Lamalchi, are part of the Hul'qumi'num speaking community. They specifically use the Island dialect of the language.

The Lamalchi mainly traveled by canoe. In September 1828, a European fur-trader counted 550 Cowichan canoes returning with fish along the Lower Fraser River.

Where the Hwlitsum Lived

Closely related groups of people lived in villages on Penelakut Island, Galiano Island, Valdez Island, and the east coast of Vancouver Island. These groups identified themselves by the names of their winter villages, such as Penelakut and Lamalcha. The Lamalcha and Penelakut families controlled access to certain lands and resources on both sides of Trincomali Channel. This included the north end of Salt Spring Island and all of Galiano Island. The Lamalchi lived on lands at Brunswick Point, Lamalcha Bay, parts of Salt Spring Island, Galiano Island, and other places, keeping others out. Until European contact in 1849, the Lamalchi usually spent November to March at Lamalcha Bay. They spent April to October at Hwlitsum (Canoe Pass). They also traveled to the Coquitlam River and Pitt River to gather plants during the growing season.

What the Hwlitsum Ate

The Lamalchi and Penelakut were the only people who regularly hunted sea-lions around the south end of the Georgia Strait. Fishing was a very important part of the Lamalchi People's lives. They fished at xegetinas (long beach) near Deas Island at the mouth of the Fraser River. They shared this fishing spot with other Hul'qumi'num speaking communities.

During their time at the winter camp, they harvested many types of seafood. This included chum salmon, winter springs, oysters, clams, cockles, mussels, crab, cod, rock-cod, halibut, sole, red snapper, prawns, shrimp, cuttlefish, sea urchins, kelp, seaweed, octopus, squid, herring, dogfish, and perch from local waters and beaches. They also hunted deer, elk, black bear, raccoon, mink, seals, otter, and grouse. They gathered plants like salal, ferns, cedar bark, alder, maple, and berries for medicines and food. They were able to store food by smoking or drying it and keeping it in boxes or bentwood boxes and hidden storage spots.

In spring, summer, and winter, their food included eulachon, spring salmon, coho salmon, sockeye salmon, steelhead, pink salmon, chum salmon, and sturgeon. They also ate clams, crab, shrimp, halibut, ling cod, smelt, flounder, trout, and dogfish. They hunted deer, mountain goat, black bear, muskrat, red fox, pheasant, mink, marten, ducks, geese, pigeon, widgeon, otter, seal, brant, and snow geese. Plants they gathered included cedar bark, cascara bark, devil's club, huckleberries, salmonberry, strawberry, salal, alder, maple, squasum berry, cattails, rhubarb, plums, crab apples, and wapato.

How Many People Lived There?

In 1824, a person named Francis Annance estimated the population to be about 1,000 people.

In 1827, George Barnston estimated that the total population of the three largest Cowichan villages was about 1,500 people. This number included Somenos and Quamichan of the Cowichan River, and the Penelakuts (and Lamalchi) of Penelakut Island. Barnston made this guess while sailing past these communities on a ship.

In 1849, an employee of the Hudson's Bay Company recorded that 122 people were living in Lamalcha Bay.

Traditional Homes

The Lamalchi traditionally lived in large homes called longhouses.