Indian country jurisdiction facts for kids

Panorama of the Fort Mojave Indian Reservation near Bullhead City, Arizona

|

|

| Colonial & Early U.S. Policy | |

|---|---|

| Cases | Johnson v. McIntosh; Cherokee Nation v. Georgia; Worcester v. Georgia |

| Legislation | Trade & Intercourse Act; Indian Removal Act; |

| Allotment | |

| Cases | U.S. v. Kagama; Talton v. Mayes; Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock |

| Legislation | Major Crimes Act; General Allotment Act (Dawes Act); Indian Citizenship Act |

| Reorganization | |

| Legislation | Indian Reorganization Act |

| Termination | |

| Cases | Tee-Hit-Ton v. U.S.; Williams v. Lee |

| Legislation | House Concurrent Resolution 108; Public Law 280; Urban Relocation Program; Termination Acts |

| Self-Determination | |

| Cases | New Mexico v. Mescalero Apache Tribe; Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe; United States v. Wheeler; Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez; Montana v. U.S.; Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe; National Farmers Unions Ins. Co. v. Crow Tribe; California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians; Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield; Duro v. Reina; Nevada v. Hicks; Atkinson Trading Co. v. Shirley; United States v. Lara; Solem v. Bartlett |

| Legislation | Indian Civil Rights Acts; Indian Gaming Regulatory Act |

Indian country jurisdiction refers to the legal power that tribal governments have over certain areas in the United States. This power has changed a lot since Europeans first settled in America. Over time, laws passed by the U.S. government and decisions made by the Supreme Court have given more or less power to tribal governments. This depends on how the federal government viewed Native American tribes at different times.

Important Supreme Court cases like Worcester v. Georgia, Oliphant v. Suquamish Tribe, Montana v. United States, and McGirt v. Oklahoma have set important rules about who has legal authority in Indian country.

Understanding Indian Country Jurisdiction History

The way the United States government has dealt with Native American tribes and their legal powers has changed many times. Historians often divide this history into six main periods. These periods show how U.S. laws and Supreme Court decisions have shaped the idea of Indian country jurisdiction.

Early U.S. Policies and Native Lands

In 1763, the British government created the Proclamation of 1763. This law set a boundary line between the British colonies and Native American lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. It stopped British colonists from moving into these Native territories.

After the United States was formed, Congress passed the Indian Intercourse Acts. These laws, first passed in 1780, helped manage relationships between Native Americans and non-Native people living on Native lands. They also helped define what "Indian Country" meant. The final version of this law was passed in 1834.

The Era of Native American Relocation

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the U.S. government started talking with Native American tribes in this new territory. Many U.S. citizens wanted this land for farming. This led to many disagreements over land ownership.

One of the first cases that allowed Americans to take Native lands was Johnson v. McIntosh. This case said that when a European nation "discovered" land in the New World, it also gained the right to take that land from the Native people. This could happen by buying the land or by winning it in a conflict.

States wanted to move Native Americans out of their territories. This led to more treaties and the controversial policy of forced relocation. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. This law allowed President Andrew Jackson to exchange Native American lands in the East for lands in the West. This act led to the tragic Trail of Tears in 1831, where many Native Americans were forced to move from their homes.

The Allotment Period: Dividing Native Lands

By the 1870s and 1880s, many people were unhappy with the government's reservation policy. Some saw Native Americans living in poverty. Others saw large areas of land being kept from white settlers. These views led to the Dawes Act, also known as the General Allotment Act of 1887.

This act divided tribal lands into smaller pieces, called allotments. Each head of a family received about 160 acres. More land was given if it was used for grazing. Other family members also received smaller amounts of land.

The government held the title to these allotments for 25 years. This was supposed to protect Native Americans from state taxes and help them learn to manage their land. However, after 25 years, many Native Americans faced high state property taxes. This often forced them to sell their land. White settlers then bought these lands, creating a "checkerboard effect." This made it very hard for Native Americans to farm or graze animals effectively.

The Dawes Act had very negative effects on Native Americans. The Native American population reached its lowest point in history around 1900, with only 250,000 people in the U.S. The amount of land owned by Native Americans also dropped sharply. In 1887, they held about 138 million acres. By 1934, this had fallen to about 48 million acres, with much of it being desert.

Reorganizing Tribal Governments

The Allotment period began to end in 1924 when Congress granted citizenship to all Native Americans born in the U.S. In 1928, the Meriam Report was released. This report showed that the Dawes Act and the allotment policy had failed.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 officially started the Reorganization period. This act stopped the practice of allotment. It aimed to protect tribes and help them create their own self-governments. Tribes could now write their own constitutions and laws, which tribal members would vote on. After many years of hardship and loss, the Indian Reorganization Act helped stop the destruction of tribal cultures and lands.

The Termination Era: 1953-1964

Unclear legal boundaries between states and tribes led to the Indian termination policy era. This era began in 1953 when Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution 108. This resolution stated that Congress wanted to make Native Americans subject to the same laws as other U.S. citizens. It also aimed to end their special status as "wards of the United States."

This termination policy was seen as a direct attack on the sovereignty of Native American nations. When a tribe was "terminated," it lost its status as a reservation or nation. This meant tribes lost their legal powers, tax protections, and were forced into a different legal system.

During this 12-year period, 109 tribes were terminated. This had severe negative effects on their education, health care, and economic stability. Some historians believe that Cold War fears played a role in this policy. Some social programs on reservations were seen as similar to socialism, which was linked to the Soviet Union.

While termination might have been seen as "freeing" tribes from government programs, it actually made it harder for Native Americans to govern themselves. Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon later moved the nation away from termination towards self-determination.

Self-Determination: Tribes Governing Themselves

By the late 1960s, the termination policy was seen as a failure. Federal policy then shifted towards self-determination. This means a group or nation has the right to govern itself independently. This policy has been in effect since the late 1960s and has greatly shaped modern Indian country jurisdiction.

One important law from this period is the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968. This act applied most of the rules from the Bill of Rights to tribal governments. It both expanded and limited tribal legal powers. It required tribal governments to follow constitutional procedures, but it also limited their independence. The act also changed Public Law 280. This meant states no longer had automatic civil and criminal legal power over Indian country unless tribes agreed through elections.

In 1983, the Supreme Court case New Mexico v. Mescalero Apache Tribe stated that state legal power can interfere with tribal self-government. This happens when "state interests are strong enough to justify the state's authority." Another case, National Farmers Union Ins. Cos. v. Crow Tribe (1985), said that parties must first try to resolve issues in tribal court before going to federal court.

However, the 2001 case Nevada v. Hicks limited tribal legal power. It ruled that tribal courts do not have automatic power over state officials who commit crimes on reservation lands.

Present Day Indian Country Jurisdiction

Today, who has legal power in Indian country is decided by many Supreme Court cases and federal laws. This applies to criminal and civil cases. Usually, the legal power of federal, state, or tribal courts depends on several things:

- Whether the people involved are Native Americans or tribal members.

- The type of crime or issue.

- Where the events of the case happened within Indian country.

To be considered a Native American for federal legal purposes, a person must be a member of a federally recognized tribe.

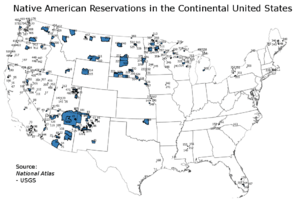

Congress defined "Indian Country" in 1948 (18 U.S.C.A. 1151) as:

- All land within any Indian reservation under U.S. government control. This includes land owned by non-Native people and roads running through the reservation.

- All Native American communities that depend on the U.S. government, whether they are inside a state or not.

- All Native American allotments where the Native American ownership has not been ended. This also includes roads running through them.

This definition means that all land within an Indian reservation is considered Indian country. This is true even if non-Native people own some of the land. Land on a reservation that was opened for non-Native settlement is still Indian country. This is unless Congress clearly stated that the land was no longer part of the reservation.

Sometimes, the boundaries of Indian country can become less clear. For example, the Devils Lake Sioux had a legal case against the North Dakota Public Service Commission. The commission was operating within reservation borders. The court ruled that the tribe had no power over privately owned lands. This was true even though more Native Americans than non-Native people lived on the reservation. This shows how the meaning of Indian Country can become less clear. This can also reduce the legal power of tribes within their own reservation borders.

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |