Indigenous specific land claims in Canada facts for kids

Indigenous Specific Land Claims, often called specific claims, are long-standing land claims made by First Nations people against the Canadian government. These claims are about promises the government made to Indigenous communities but didn't keep.

These promises often relate to how the government managed First Nation land and other important things. They also cover whether historic treaty agreements and other deals between First Nations and the Crown (the government) were followed. For example, this could be about the government mismanaging Indigenous land or money under the Indian Act. When specific claims are settled, the government usually gives money to the First Nation community. In return, the First Nation agrees to give up their claim to that specific piece of land. The government does not take land from other people to settle these claims.

Specific claims are based on the government's legal duties to First Nations. They are different from comprehensive land claims or modern treaties. Specific claims cannot be based on Aboriginal titles (original ownership of land) or punitive damages (extra money for punishment).

In 2008, a special independent group called the Specific Claims Tribunal was created. This group makes decisions that must be followed. It helps solve claims that were not accepted for talks or where both sides couldn't agree on fair payment.

The Canadian government started to accept specific claims in 1973. Since then, First Nation communities have submitted 1,844 claims. Of these, 935 have been solved. As of March 2018, the government was talking about settling 460 claims. Another 250 claims were accepted for talks, and 71 claims were before the Specific Claims Tribunal. About 160 specific claims were still being looked at.

Contents

Why Do Land Claims Happen?

The relationship between Indigenous peoples and European colonists often involved broken promises. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 said that only the British Crown could make treaties or agreements with First Nations. These agreements include the Peace and Friendship Treaties in the Maritimes. There were also 11 Numbered Treaties with First Nations in parts of Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, and the Northwest Territories. Many other regional treaties were made in southern Ontario and British Columbia.

However, the land promised in these treaties was sometimes never given. Other times, the Canadian government illegally took land under the Indian Act. Or, people working for the Department of Indian Affairs wrongly sold or leased reserve land for their own gain. In other cases, Indigenous groups were not paid enough for reserve lands that were sold or damaged. Today's specific claims come from these old, unfulfilled treaty promises.

How Did Specific Claims Start?

Some First Nations communities began pushing for their claims as early as the 1800s and early 1900s. But from 1927 to 1951, it was against the law for Indigenous groups to take the government to court over land claims. They also couldn't use their own funds to sue the government. This meant land claims were mostly ignored. In 1947, a group of lawmakers suggested that Canada create a "Claims Commission." This would be like the Indian Claims Commission in the United States, which started in 1945. Again, between 1959 and 1961, it was suggested that Canada look into land problems for First Nations in British Columbia and Kanesatake, Quebec.

Canada started accepting specific claims for talks in 1973. A government policy created the Office of Native Claims within the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs. This office was meant to talk about Indigenous land claims. These claims were put into two groups: comprehensive claims and specific claims. Comprehensive claims deal with the rights of Indigenous people to their traditional ancestral lands. Specific claims, on the other hand, deal with particular times when the government broke its promises to Indigenous communities.

By 1982, nine years after the Office of Native Claims was created, only 12 out of 250 claims had been settled. Indigenous communities complained that the Office was both checking and negotiating each claim. They felt this was an unfair situation. They asked for an independent group to handle the talks.

In 1992, the Canadian government created the Office of the Indian Claims Commissioner. Its job was to look into claims that the Office of Native Claims had refused to discuss. However, the Commissioner's power was limited to making suggestions that didn't have to be followed. This made it ineffective. In their yearly reports, Claims Commissioners often suggested creating a new independent group. This group would oversee specific claims and could make decisions that both sides had to follow, especially when Canada and First Nations couldn't agree on fair payment. This group was finally created in 2008. It was called the Specific Claims Tribunal, where independent judges look at each claim individually.

How Do Specific Claims Work?

First Nation communities can start the specific claims process by sending a claim to the Canadian government. These claims must meet certain rules set by the Department of Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs. If a claim doesn't meet these rules, it's immediately rejected and must be sent again. If a claim meets the rules, it goes into a 3-year period where the government checks if a promise was broken. If the government decides no promise was broken, the claim is closed. The First Nation can then change their claim and send it again, or challenge the government's decision at the Specific Claims Tribunal.

If the claim is accepted for talks, there is a 3-year period for negotiations. During this time, the government and the First Nation try to agree on fair payment for the broken promise. The payment is usually money and does not typically include adding more land to the reserve. If no agreement is reached, the First Nation can take their claim to the Specific Claims Tribunal for a decision.

Examples of Claims

Here are a few examples of specific claims that are still being worked on.

The Atikamekw of Opitciwan's Claims

The Atikamekw of Opitciwan community filed four specific claims with the government. One was about losses from their village flooding in 1918. This happened because the La Loutre Dam and the Gouin Reservoir were built. Another claim was about the delay in creating their reserve. A third was about the size of the reserve. And a final claim was about the dam being raised, which caused more floods in the 1940s and 1950s.

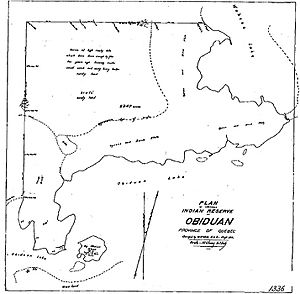

In 1912, Chief Gabriel Awashish and his group of over 150 Atikamekw people settled where Obeydjiwan, Quebec is today. This was on the coast of a lake with the same name. The area was surveyed in 1914 to prepare for a reserve. The group was promised 3,000 acres for this reserve, but the surveyor only measured 2,290 acres. In 2016, the Specific Claims Tribunal decided that the government did not try hard enough to give the First Nation the 3,000-acre reserve. So, the government should pay the First Nation for the missing 710 acres.

In 1918, the La Loutre Dam was finished, and it caused the village of Obeydjiwan to flood. All the homes and belongings of the community were destroyed. As early as 1912, the government knew the dam would flood the village but did not tell the community. Payments for these damages were delayed, and some Atikamekw people were not paid enough, or not at all. The Obeydjiwan reserve was finally created in 1950. The 1950 reserve was 2,290 acres. It included land outside the area first planned for the reserve to make up for the land flooded in 1918. In 2016, the Specific Claims Tribunal ruled that the delay in creating the reserve was too long. This caused the Atikamekw to lose money from logging.

In 2013, a Canadian surveyor named Éric Groulx told the Specific Claims Tribunal that the original surveyor, Walter Russell White, made a mistake. He said the land surveyed in 1914 was actually 2,760 acres, not 2,290 acres. This error led to more mistakes when calculating the flooded land in 1918. This flooded land was used to add land outside the proposed reserve. So, the Specific Claims Tribunal decided that the First Nation was not properly paid for the land lost in the flooding.

The Kanesatake Claim

The Kanesatake land claim is one of the most debated land claims in Canada. This is partly because of its importance during the Oka Crisis.

The claim started when the Sulpician mission was set up near Lac des Deux-Montagnes. Land was set aside for the Mohawks to live on in 1717. However, in 1721, King Louis XV of France gave the Seigneurie des Deux-Montagnes (land owned by a lord) only to the Sulpicians. This gave them the legal right to the land. In the 1800s, the Mohawks of Kanesatake began complaining to the British authorities that the Sulpicians were treating them badly. They then found out that the land they had lived on for over 150 years, and thought they owned, was not theirs. They started pushing their claim with the government. The case went to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1910, which decided that the Sulpicians owned the land. In 1956, the Canadian government bought 6 square kilometers of land from the Sulpicians for the Mohawks to live on. But this land was not given reserve status.

In 1975, the Mohawk Council submitted a comprehensive land claim. They said they had Aboriginal title to lands along the St. Lawrence River, the Ottawa River, and Lac des Deux-Montagnes. The government rejected this claim. In 1977, the Mohawk Council of Kanesatake filed a specific claim about the former seigneurie. This claim was rejected nine years later because it didn't meet key legal rules. In 2002, the government passed a new law, Bill S-24. This law said that the government's relationship with Kanesatake was like its relationship with First Nations that have a reserve.

In 2008, the Canadian government agreed to talk about the Mohawks of Kanesatake's claim again under the specific claims policy. Fred Caron, a former Assistant Deputy Minister, was chosen to lead the government's talks for this case.

What Are the Criticisms?

First Nations have long been unhappy with the Specific Claims process for several reasons. They felt it was unfair that the government both checked the claims and negotiated them. They also thought the process was too slow. Another issue was that they usually only got money, not land, as payment. People also criticized the lack of clear information about how specific claims funds were used. Finally, they were unhappy about having to give up their land rights to get payment. The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) praised the creation of the Specific Claims Tribunal in 2008. This helped with some problems, but many issues with the Specific Claims Policy, especially about giving up indigenous rights, were still unsolved.

In 2018, the Fraser Institute published a report by political scientist Tom Flanagan. He said that First Nation communities who received money from specific claims did not score better on the Well-Being Index of First Nations than those who didn't. He argued that specific claims were a very expensive problem for the government. He also said that numbers showed no positive impact from settling these claims. Flanagan also criticized changes made over the years to the specific claims policy that made it easier for First Nations. He blamed these changes for creating a growing pile of new claims each year. To settle all specific claims once and for all, Flanagan suggested setting a deadline. After this deadline, First Nations would no longer be able to file new specific claims. He said this would be like the United States' Indian Claims Commission, which had a 10-year period to file claims. This allowed them to settle all their Indigenous land claims in less than 40 years.

In response to Flanagan's report, lawyers Alisa Lombard and Aubrey Charette wrote an opinion piece. They said that the purpose of Specific Claims is to bring justice to First Nation communities who were cheated. It is not a welfare program. So, comparing communities who settled a claim with those who didn't, using the Well-Being Index, is not relevant to what the Specific Claims process is trying to achieve.

A 2018 report by the British Columbia Specific Claims Working Group found that the government failed to meet its legal duty to check claims within a 3-year period more than 65% of the time. On average, the government finishes checking claims 5 months after the legal deadline. In an open letter to Crown-Indigenous Relations minister Carolyn Bennett, the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs said that this "not following laws made to protect Indigenous Peoples' rights... goes against every public promise your government has made about making things right." Stephan Matiation, a director at Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, replied that his team does not have enough staff, which causes delays in checking claims.

See also

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |