Ingeborg of Denmark, Queen of France facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ingeborg of Denmark |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Queen consort of France | |

| Tenure | 15 August 1193 – 5 November 1193 |

| Coronation | 25 August 1193 |

| Tenure | 1200 – 14 July 1223 |

| Born | 1174 |

| Died | 29 July 1237 (aged 62–63) Priory of Saint-Jean-de-l’Ile |

| Burial | Church of Saint-Jean-de-l’Ile |

| Spouse | Philip II of France |

| House | House of Estridsen |

| Father | Valdemar I of Denmark |

| Mother | Sofia of Minsk |

Ingeborg of Denmark (French: Ingeburge; 1174 – 29 July 1237) was a Queen of France. She became queen by marrying Philip II of France. Ingeborg was the daughter of Valdemar I of Denmark and Sofia of Minsk. Her life as queen was full of challenges, as her husband tried to end their marriage for many years.

Contents

A Royal Marriage and a Quick Change of Mind

Ingeborg married Philip II Augustus of France on August 14, 1193. Philip had recently lost his first wife. Ingeborg's brother, King Canute VI of Denmark, gave her a large amount of money and goods as a wedding gift, called a dowry. A writer at the time, Stephen of Tournai, described Ingeborg as "very kind, young in age but old in wisdom."

However, the very next day after the wedding, King Philip changed his mind. He wanted to end the marriage and send Ingeborg back to Denmark. Ingeborg was very upset. She went to a convent in Soissons and complained to Pope Celestine III.

Three months later, Philip called a meeting of church leaders in Compiègne. He had them create a fake family tree. This tree wrongly showed that he and Ingeborg were related. Back then, church law (called Canon law) said people could not marry if they shared an ancestor within the last seven generations. So, the church meeting declared their marriage was not valid.

Ingeborg protested again. The Danes sent people to talk to Pope Celestine III. They proved the family tree was false. The Pope then said Philip's attempt to end the marriage was wrong. He also told Philip he could not marry anyone else. But Philip ignored the Pope.

Years of Imprisonment and Support

For the next 20 years, Ingeborg was held captive in different French castles. At one point, she spent over ten years in the castle of Étampes, southwest of Paris. Her brother, Knud VI, and his advisors kept working to get her marriage recognized. Many of Philip's own advisors in France also supported Ingeborg.

Historians believe Philip wanted to marry Ingeborg for political reasons. He likely wanted to improve relations with Denmark. The two countries had been on different sides in a disagreement about who should rule the Holy Roman Empire. Philip also wanted more allies against the powerful Angevin family, who ruled England. He had asked Denmark for help with their navy and for any claims Denmark had to the English throne. Ingeborg's brother, Knud VI, only agreed to give her a dowry of 10,000 silver marks.

The Pope's Strong Defense

Pope Celestine III tried to help Queen Ingeborg, but he couldn't do much at first.

A French-Danish churchman named William of Æbelholt helped Ingeborg. He created a real family tree of the Danish kings. This showed that Ingeborg and Philip were not related, proving Philip's claim was false.

In June 1196, Philip married another woman, Agnes of Merania. Ingeborg wrote to Pope Celestine III, expressing her sadness. Her letters in Latin showed how unfairly she was treated. Then, in 1198, a new pope, Pope Innocent III, took over. He declared Philip's new marriage was not valid because his marriage to Ingeborg was still legal. The Pope ordered Philip to send Agnes away and take Ingeborg back.

Philip's response was to lock Ingeborg away in the Château d'Étampes in Essonne. She was a prisoner in a tower. She didn't always get enough food, and no one was allowed to visit her, except for two Danish priests one time. Meanwhile, Philip brought Agnes back and continued to live with her. They had two children. Because of this, Philip was excommunicated in 1200. This meant he was cut off from the church. The Pope also placed France under an interdict, which meant many church services were stopped in the country. Philip finally said he would obey in September 1200, and the interdict was lifted. But he broke his promise later. Even though Ingeborg was still considered queen, she remained a prisoner. Agnes died the next year.

In 1201, Philip asked the Pope to declare his children with Agnes legitimate (meaning they were legally recognized). The Pope agreed to get Philip's political support. However, later that year, Philip again asked to end his marriage to Ingeborg. He made false accusations, claiming Ingeborg had tried to harm him on their wedding night. This attempt to get a divorce also failed.

Reconciliation and Later Life

Philip finally made peace with Ingeborg in 1213. He did this not out of kindness, but because he wanted to strengthen his claim to the throne of Kingdom of England through his connection to the Danish royal family. Later, when Philip was dying in 1223, he reportedly told his son, Louis VIII, to treat Ingeborg well. Both Louis VIII and his son, Louis IX, later recognized Ingeborg as a true queen.

After this, Ingeborg spent most of her time at a priory (a type of monastery) called Saint-Jean-de-l'Ile. She had founded this priory herself. It was near Corbeil, on an island in the Essonne river. She lived more than 14 years longer than her husband.

Ingeborg of Denmark died in 1237 or 1238. She was buried in the Church of the Order of St John in Corbeil.

See also

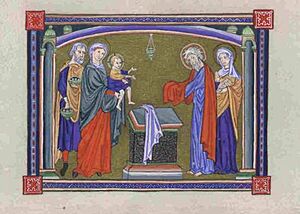

- Ingeborg Psalter

Other Sources

- Alex Sanmark The Princess in the Tower (History Today February 2006)

- Gérard Morel (1987) Ingeburge, la reine interdite (Payot, collection Les romans de l'Histoire) ISBN: 978-2228751209

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |