Interior Alaskan wolf facts for kids

The Interior Alaskan wolf (also called the Yukon wolf) is a type of gray wolf found in North America. Its scientific name is Canis lupus pambasileus. These wolves live in Interior Alaska in the United States and in Yukon, British Columbia, and the Northwest Territories in Canada. They often live in cold, open areas like the tundra.

Quick facts for kids Interior Alaskan wolf

Yukon wolf |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| An Interior Alaskan wolf in Denali National Park | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: |

C. l. pambasileus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus pambasileus Elliot, 1905

|

|

|

|

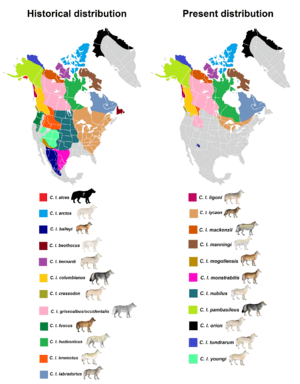

| Where gray wolf types have lived in North America | |

Contents

About the Interior Alaskan Wolf

This wolf is officially recognized as a subspecies of Canis lupus, which is the gray wolf. It was first described in 1905 by an American scientist named Daniel Giraud Elliot. He called it Canis pambasileus.

Elliot noticed that this wolf had very large and strong teeth and skull. These were bigger than those of other wolves of similar body size. The wolf's fur can be many colors, from black to white, or a mix of both.

Physical Features

Size and Appearance

Interior Alaskan wolves are quite large. They stand about 85 centimeters (33.5 inches) tall. Male wolves usually weigh around 56.3 kilograms (124 pounds). Females are a bit lighter, averaging 38.5 kilograms (85 pounds). However, their weight can range from 32 kg (70 lb) to 60 kg (132 lb).

The most common fur color for these wolves is a mix of tawny grey or tan. But they can also be white or black. These wolves typically live for 4 to 10 years. Some have been known to live up to 12 years.

Pack Life and Reproduction

Interior Alaskan wolves live in groups called packs. An average pack has about 7 to 9 wolves. A pack usually includes a mother and father wolf, and their young. The mother and father are typically the only ones in the pack that have pups.

A young wolf that leaves its pack might travel very far to find a mate. They can travel up to 500 kilometers (310 miles). Wolves can start having pups when they are about 1 year old. A mother wolf usually has 4 to 6 pups in one litter.

Health and Diseases

Like many wild animals, these wolves can get sick. Diseases like rabies and distemper can affect them. Sometimes, these diseases can even change how stable the wolf population is in certain areas.

Where They Live

This wolf lives in the interior parts of Alaska in the United States. It also lives in Yukon, Canada. However, they do not live in the very cold tundra region along the Arctic Coast.

Yukon wolves mostly live in boreal forests, which are dense evergreen forests. They also live in alpine and subalpine areas, which are high mountain regions. The population in Canadian Yukon is estimated to be around 5,000 wolves.

The number of wolves in an area depends on how much prey is available. In places with more prey, there are more wolves.

What They Eat

The diet of the Interior Alaskan wolf changes depending on where they live. In southern Yukon, their main food is moose. They also eat boreal woodland caribou and Dall sheep. In the North Slope, their main food is Barren-ground caribou.

When hunting moose, wolves often target calves or older, weaker moose. Wolves usually succeed in catching a moose about 10% of the time. A pack might kill a moose every 5 to 6 days and eat from it for 2 to 3 days. Moose tend to stand their ground when hunted.

Caribou, on the other hand, tend to run away, which can make them easier for wolves to catch. Wolves usually kill a caribou every 3 days in winter and eat from it for about a day. Dall sheep are also eaten, especially when moose and caribou are harder to find.

History and Conservation

Early History

Long ago, before European settlers arrived, Native people in Canada hunted these wolves for their fur. This continued into the 1800s. Settlers also traded wolf furs with Native tribes, who used them to line their clothes.

In the 1950s, people started mapping the wolf population in Yukon. At that time, many people had negative ideas about wolves. This led to programs that tried to reduce wolf numbers, sometimes by poisoning them.

Yukon Wolf Conservation Plan

In the 1980s, the Yukon government created a plan called the Yukon Wolf Conservation and Management Plan. The goal was to find ways to manage the wolf population. Studies were set up to understand how reducing wolf numbers would affect other animals.

One rule was that wolf population reduction would only happen in one specific test area at a time. Also, no hunting of other animals would be allowed in these test areas. This helped scientists understand the results better.

Later, in the 2000s, the plan led to strict rules for making sure wolves would be protected in the long term. It also limited how much wolf control could happen in the future. The plan aimed to teach people why wolves are important. It also made wolf hunting laws stricter. However, some environmental groups were against any form of wolf control.

Efforts to Help Caribou Herds

- Finlayson Recovery Program (1983–1992): This program started because people noticed that the Finlayson caribou herd was getting smaller. The government reduced the number of wolf packs in the area. They also limited caribou hunting. As a result, the number of caribou more than doubled. The wolf numbers also returned to normal after the program ended. However, the caribou numbers started to drop again later.

- Aishihik Recovery Program (1992–1997): This program aimed to reduce about 80% of the wolf population in a specific area of southwest Yukon. This was done using methods like aerial hunting and traps. Some wolves were also sterilized (made unable to have pups). The goal was to see if fewer wolves would lead to more caribou, moose, and Dall sheep. The study found that wolves greatly affected the moose population. They also affected the caribou population as a whole. However, the Dall sheep population was not affected. The study also suggested that sterilizing wolves was better than killing them, as it did not change wolf behavior.

- Chisana Recovery Program (1996–present): This program began because the Chisana caribou herd had dropped from over 3,000 in the 1960s to about 400 by the 1990s. The government stopped all caribou hunting in the area. Instead of hunting wolves, they focused on helping the caribou breed. This effort has been quite successful so far.

Aerial Wolf Hunting in Alaska

In 2009, a plan was approved in Alaska that allowed the state to hire helicopters to kill wolves. This plan was approved without public discussion. Many groups were upset, saying it ignored scientific ways of managing wildlife.

Soon after, an aerial wolf hunt began in Alaska. Many wolves were killed quickly, including some that had tracking collars for research. The National Park Service was very unhappy about losing these collared wolves, as they were part of a long-term study. They stated that if the hunt continued, it would leave very few wolves in the area.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Lobo del Yukón para niños

In Spanish: Lobo del Yukón para niños