J. Howard Moore facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

J. Howard Moore

|

|

|---|---|

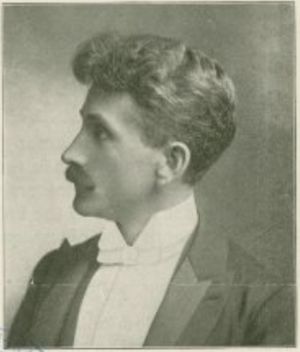

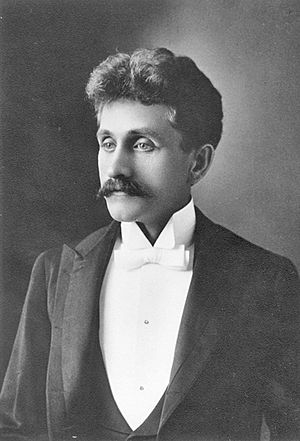

Moore, c. 1900–1914

|

|

| Born |

John Howard Moore

December 4, 1862 |

| Died | June 17, 1916 (aged 53) |

| Resting place | Excelsior Cemetery, Mitchell County, Kansas, U.S. |

| Other names | Silver tongue of Kansas |

| Education |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Animal rights and ethical vegetarianism advocacy |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) |

Jennie Louise Darrow

(m. 1899) |

| Relatives | Clarence Darrow (brother-in-law) |

| Signature | |

John Howard Moore (born December 4, 1862 – died June 17, 1916) was an American scientist, thinker, and teacher. He was also a kind person who believed in fairness for everyone. He is known as one of the first people to speak up for animal rights and for choosing to be a vegetarian for moral reasons.

Moore was a very active writer. He wrote many articles, books, and essays. These covered topics like animal rights, how we learn, what is right and wrong, and how living things change over time (evolution). He also talked about being kind to others and how society could be better. He was a great speaker, so good that people called him the "silver tongue of Kansas."

Moore was born in Indiana in 1862 and grew up in Missouri. At first, he believed that animals were only here to help humans. But when he went to college, he learned about Darwin's theory of evolution. This changed his mind. He began to think that animals have their own value, not just what they can do for us. Because of this, he became a vegetarian.

While studying at the University of Chicago, he became interested in socialism, a way of thinking about how society should be fair. He helped start a vegetarian eating club at the university. He also won a big speaking contest about prohibition, which was about banning alcohol. Moore was an important member of the Chicago Vegetarian Society. He tried to make it like a British group called the Humanitarian League, which he also belonged to.

In 1895, Moore gave a speech called Why I Am a Vegetarian. It explained why he chose not to eat meat. For the rest of his life, he taught in Chicago. He also kept giving talks and writing books.

In 1899, Moore published his first book, Better-World Philosophy. In it, he talked about problems in the world and how he thought things should be. His most famous book, The Universal Kinship, came out in 1906. In this book, he said that all living things are connected. He believed we should be kind to all sentient beings (creatures that can feel things). He shared more of his ideas in The New Ethics the next year. Moore also wrote books to help teachers teach morals in schools. He later wrote two books about evolution. Moore passed away at 53 in Jackson Park, Chicago.

Contents

About J. Howard Moore

Early Life and Learning

John Howard Moore was born on December 4, 1862, near Rockville, Indiana. He was the oldest of six children. When he was six months old, his family moved to Missouri. For the first 30 years of his life, his family moved around Kansas, Missouri, and Iowa.

Moore grew up in a Christian family. This taught him that humans were meant to rule over the Earth and its animals. He lived on a farm and enjoyed hunting. He later realized that he and his community saw animals as things to be used.

Moore went to school until he was 17. Then he studied at a college in Missouri for a year. From 1880 to 1884, he studied at Oskaloosa College in Iowa. He then went to Drake University. Studying science there, he learned about Darwin's theory of evolution. This made him change his beliefs. He started to think that animals have their own value, separate from humans. This led him to become a vegetarian for ethical reasons.

In 1885, Moore was struck by lightning. He was burned and temporarily lost his sight and ability to speak. He recovered after six days, but he had bad headaches for the rest of his life. In 1886, he tried to become a politician but did not win.

Moore studied law in Kansas. In 1889, he started giving lectures for a company. He was so good at speaking that people called him the "silver tongue of Kansas." He gave talks in Kansas, Missouri, and Iowa.

In 1890, Moore wrote his first pamphlet, A Race of Somnambulists. In it, he criticized how humans were cruel to animals. That summer, he also studied how to improve his singing and speaking voice in New York.

From 1890 to 1893, Moore continued to be a lecturer. He also gave talks for the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, a group that wanted to ban alcohol. He also worked as a reporter for a local newspaper.

In 1894, Moore started studying at the University of Chicago. There, he became interested in socialism, which is about making society fairer for everyone. He helped create the Vegetarian Eating Club at the university. He was its president in 1895. He was also vice president of the university's prohibition club.

Moore was an important member of the Chicago Vegetarian Society. He also belonged to the Humanitarian League, a group in Britain that worked for animal welfare. Moore helped shape the Chicago group to be like the British one. In 1895, he gave a speech to the society, which was published as Why I Am a Vegetarian. In this speech, he explained why he chose not to eat meat.

A month after this speech, Moore won first place in a speaking contest at the University of Chicago. He then won first place at the state prohibition contest in Illinois. He even won the national contest in Cleveland. A newspaper described Moore as a strong supporter of women's suffrage (the right for women to vote).

Moore graduated in April 1896 with a degree in zoology. That summer, he became a professor at Wisconsin State University. He taught about how society changes.

In 1898, Moore started writing a full-page column in the Chicago Vegetarian journal. This made him more influential in the vegetarian society. In the same year, he began teaching at Crane Technical High School. He taught there for the rest of his life. He also taught at other schools in Chicago.

In 1899, he married Jennie Louise Darrow. She was an elementary school teacher who also supported animal rights and vegetarianism. She was the sister of the famous lawyer Clarence Darrow. The couple moved back to Chicago.

Later Life and Work

In 1899, Moore published his first book, Better-World Philosophy. In this book, he talked about how he wanted to change how people see the world. He believed that all living things are connected. Moore argued that if a creature can feel things (is sentient), then we should consider its well-being. The book was praised by other thinkers. It also caught the attention of Henry S. Salt, who founded the Humanitarian League. Salt wrote a good review of the book. Salt and Moore became close friends and wrote many letters to each other, even though they never met in person.

Moore was a strong critic of America's actions in the Philippine–American War. He wrote an article in 1899 called "America's Apostasy," speaking out against it.

In 1906, Moore published The Universal Kinship. In this book, he explored how humans and other animals are connected physically, mentally, and morally. He argued that all beings have rights. He believed that the Golden Rule (treat others as you want to be treated) should apply to all living things. The book received many good reviews. Famous writers like Mark Twain and Jack London supported it. Henry S. Salt called it the "best ever written in the humanitarian cause."

In November 1906, Moore gave a speech called "The Cost of a Skin." This speech caused some debate at a meeting of the American Humane Association. In his speech, Moore said that wearing fur and feathers for fashion was "heartless and unkind." Some people in the audience cheered, while others were silent. Two women even left the room. The speech was later published in his book The New Ethics (1907).

Yes, do as you would be done by—and not to the dark man and the white woman alone, but to the sorrel horse and the gray squirrel as well; not to creatures of your own anatomy only, but to all creatures. You cannot go high enough nor low enough nor far enough to find those whose bowed and broken beings will not rise up at the coming of the kindly heart, or whose souls will not shrink and darken at the touch of inhumanity. Live and let live. Do more. Live and help live. Do to beings below you as you would be done by beings above you. Pity the tortoise, the katydid, the wild-bird, and the ox. Poor, undeveloped, untaught creatures! Into their dim and lowly lives strays of sunshine little enough, though the fell hand of man be never against them. They are our fellow-mortals. They came out of the same mysterious womb of the past, are passing through the same dream, and are destined to the same melancholy end, as we ourselves. Let us be kind and merciful to them.

In 1907, Moore published The New Ethics. In this book, he talked about how our understanding of right and wrong should grow. He believed it should include what we learn from Darwin's theory of evolution. Moore was confident that humans would become less selfish over time.

Besides teaching and writing, Moore often gave talks. He spoke about vegetarianism, treating animals kindly, and stopping vivisection (experiments on live animals). He also wrote articles for groups that supported animal welfare and humane education. He also supported the temperance movement, which aimed to reduce alcohol use.

In 1908, Moore taught courses at the University of Chicago. These included basic zoology and the evolution of farm animals. In October of that year, Moore supported Eugene V. Debs for president. He gave a speech for the Young People's Socialist League. In the next year, he criticized Theodore Roosevelt for his hunting trip to Africa. Moore said Roosevelt had "done more... to dehumanise mankind than all the humane societies can do to counteract it in years."

In 1909, a law was passed in Illinois that required teaching morals in public schools. Moore was happy about this law. He started preparing materials to help teachers. In 1912, he published Ethics and Education to help teachers with the new rules. He also published High-School Ethics: Book One. This book was meant to be the first part of a four-year high school course. It covered topics like school ethics, caring for pets, women's rights, and good habits. Moore also wrote a pamphlet called The Ethics of School Life.

In 1911, Moore wrote to his friend Salt about struggling with sadness and being overworked. He felt he had put a lot of effort into his books.

In February 1912, a meeting of the Schoolmasters' Club of Chicago was interrupted because some members disagreed with Moore's ideas. Moore replied, "I am a radical and a socialist, but I do not allow my radicalism nor my socialism to enter into my teachings."

Moore gave a speech in 1913 at an international conference against vivisection and for animal protection. He said that vivisection and eating meat both come from the idea that humans are superior. He argued that Darwin's On the Origin of Species showed that humans are not unique or superior.

In 1914, Moore published The Law of Biogenesis. This book was based on his lectures at Crane Technical High School. It described how living things repeat the evolutionary development of their ancestors.

Moore published Savage Survivals in 1916. This book was a collection of his lectures. It covered the evolution of farm animals and how some old, "savage" traits still exist in humans today.

In June 1916, Moore wrote an article that was critical of religion. He said it was "outdated today, with our science and understanding." Moore also finished a book called The Life of Napoleon, but it was not published.

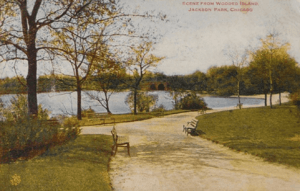

His Passing

Moore passed away on June 17, 1916, on Wooded Island in Jackson Park, Chicago. He was 53 years old. He often visited the island to watch and study birds. Moore had been ill for many years and had chronic pain from a surgery in 1911. He had also often felt sad about how little people cared about the suffering of animals. In a note found on his body, he wrote about his struggles and his love for his family and animals.

His death was officially ruled as being caused by a "temporary fit of insanity." His wife wanted his body to be cremated and his ashes buried near his favorite river. His brother-in-law, Clarence Darrow, was very sad about Moore's death. He gave a speech at the funeral, calling Moore a "dead dreamer." However, Moore's remains were buried in Excelsior Cemetery in Kansas, near his old home.

His Impact

An article published after Moore's death called him a "misanthrope" (someone who dislikes people). However, the Humanitarian League's journal described him as "one of the most devoted and distinguished humanitarians." Louis S. Vineburg, who met Moore at a lecture, also wrote a personal memory of him.

Henry S. Salt, Moore's long-time friend, was disappointed that most English animal welfare journals did not cover Moore's death more positively. Salt dedicated his 1923 book The Story of My Cousins to Moore. In his 1930 autobiography, Salt wrote about their strong friendship, even though they never met. Some of Moore's letters to Salt were included in a later edition of The Universal Kinship.

Jack London, who had supported The Universal Kinship, was very moved by Moore's death.

Moore's ideas were generally more accepted in Britain than in the United States during his time.

See also

- List of animal rights advocates

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |