Jacques Hadamard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

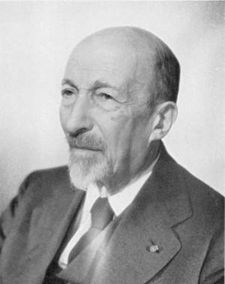

Jacques Hadamard

|

|

|---|---|

Jacques Salomon Hadamard

|

|

| Born | 8 December 1865 Versailles, France

|

| Died | 17 October 1963 (aged 97) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure |

| Known for | Hadamard product Proof of prime number theorem Hadamard matrices |

| Awards | Grand Prix des Sciences Mathématiques (1892) Prix Poncelet (1898) CNRS Gold medal (1956) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions | University of Bordeaux Sorbonne Collège de France École Polytechnique École Centrale Paris |

| Thesis | Essai sur l'étude des fonctions données par leur développement de Taylor (1892) |

| Doctoral advisor | C. Émile Picard Jules Tannery |

| Doctoral students | Maurice René Fréchet Marc Krasner Paul Lévy Szolem Mandelbrojt< André Weil |

| Signature | |

|

|

Jacques Salomon Hadamard (born December 8, 1865 – died October 17, 1963) was a famous French mathematician. He made very important discoveries in many areas of math. These included number theory, which studies whole numbers, and complex analysis, which deals with complex numbers. He also worked on differential geometry, which looks at shapes and spaces, and partial differential equations, which are special math problems.

Contents

Life and Early Career

Jacques Hadamard was born in Versailles, France. His father, Amédée Hadamard, was a teacher. Jacques went to school at Lycée Charlemagne and Lycée Louis-le-Grand. His father taught at the latter school.

In 1884, Jacques Hadamard joined the École Normale Supérieure. He had ranked first in the entrance exams for both this school and the École Polytechnique. He learned from many great teachers there.

Doctorate and First Awards

Hadamard earned his doctorate degree in 1892. In the same year, he won the Grand Prix des Sciences Mathématiques. This award was for his important work on the Riemann zeta function. This is a complex mathematical function.

In 1892, Hadamard married Louise-Anna Trénel. They had three sons and two daughters together.

Work in Bordeaux

The next year, in 1893, Hadamard became a lecturer at the University of Bordeaux. While there, he proved his famous Hadamard's inequality. This inequality is about determinants, which are special numbers linked to matrices. His work led to the discovery of Hadamard matrices.

In 1896, he made two big contributions to mathematics. He proved the prime number theorem. This theorem describes how prime numbers are spread out. Another mathematician, Charles Jean de la Vallée-Poussin, also proved it around the same time. Hadamard used complex function theory for his proof.

Also in 1896, he won the Bordin Prize. This was for his work on geodesics. Geodesics are the shortest paths between two points on a curved surface. He studied them in differential geometry of surfaces and dynamical systems. Later that year, he became a Professor of Astronomy and Rational Mechanics in Bordeaux. His important work on geometry continued. He studied geodesics on surfaces with negative curvature. For all his work, he received the Prix Poncelet in 1898.

Political Involvement

Hadamard became more involved in politics after the Dreyfus affair. This event touched him personally because his second cousin was married to Alfred Dreyfus. Hadamard became a strong supporter of Jewish causes. Even though he was an atheist, he stood up for what he believed was right.

Return to Paris

In 1897, Hadamard moved back to Paris. He worked at the Sorbonne and the Collège de France. In 1909, he became a Professor of Mechanics at the Collège de France. He also held positions at the École Polytechnique and the École Centrale.

In Paris, Hadamard focused on problems in mathematical physics. He worked on partial differential equations and calculus of variations. He also helped create the field of functional analysis. He introduced the idea of a well-posed problem. This is a problem that has a unique solution that changes smoothly with the input. He also developed the method of descent for solving partial differential equations. He wrote an important book on this topic. Later in his life, he wrote about probability theory and how to teach math.

International Recognition and War Years

Hadamard was elected to the French Academy of Sciences in 1916. He also became a foreign member of many other academies. These included the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. He visited the Soviet Union and China to meet with mathematicians.

When Second World War started, Hadamard stayed in France. In 1940, he escaped to southern France. The government allowed him to leave for the United States in 1941. He worked at Columbia University in New York. In 1944, he moved to London. He returned to France after the war ended in 1945.

Later Life and Legacy

Hadamard received an honorary doctorate from Yale University in 1901. In 1956, he was awarded the CNRS Gold medal. This was for his amazing lifetime achievements in mathematics. He passed away in Paris in 1963, at the age of ninety-seven.

Many famous mathematicians were Hadamard's students. These included Maurice René Fréchet, Paul Lévy, Szolem Mandelbrojt, and André Weil.

On Creativity in Math

Jacques Hadamard wrote a book called Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field. In this book, he explored how mathematicians think and come up with new ideas. He used his own experiences and those of other scientists.

Hadamard found that mathematical thinking often happens without words. Instead, it might involve mental images. These images can represent the whole solution to a problem. He asked 100 leading physicists how they did their work.

He described how mathematicians like Carl Friedrich Gauss and Henri Poincaré saw entire solutions suddenly. Hadamard explained the creative process in four steps:

- Preparation: Gathering information and working on the problem.

- Incubation: Taking a break from the problem, letting ideas develop in the mind.

- Illumination: The "aha!" moment when the solution suddenly appears.

- Verification: Checking the solution to make sure it is correct.

See also

In Spanish: Jacques Hadamard para niños

In Spanish: Jacques Hadamard para niños

- List of things named after Jacques Hadamard

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |