James Ford Rhodes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Ford Rhodes

|

|

|---|---|

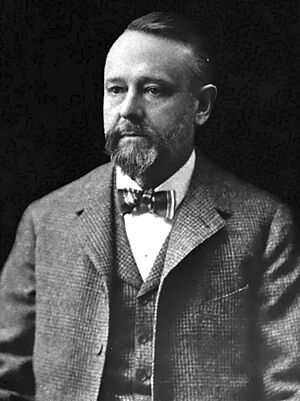

Rhodes in 1902

|

|

| Born | May 1, 1848 |

| Died | January 22, 1927 (aged 78) |

| Education |

|

|

Notable work

|

A History of the Civil War, 1861-1865 |

| Awards | Pulitzer Prize for History (1918) |

| 14th President of the American Historical Association | |

| In office 1899 |

|

| Preceded by | George Park Fisher |

| Succeeded by | Edward Eggleston |

James Ford Rhodes (born May 1, 1848 – died January 22, 1927) was an American businessman and a famous historian. He was born in Cleveland, Ohio. After making a lot of money in the iron, coal, and steel industries, he stopped working in business by 1885. He then spent his time studying history and writing books.

Rhodes wrote a seven-volume history of the United States starting from 1850. These books were first published between 1893 and 1906. An eighth volume was added in 1920. Another important book he wrote was A History of the Civil War, 1861–1865 (1918). This book won the second-ever Pulitzer Prize for History.

Contents

Early Life and Education

James Ford Rhodes grew up in Cleveland, Ohio. This area was settled by many people from New England, just like his parents. His father, Daniel P. Rhodes, was a Democrat. He was a friend of Stephen A. Douglas. During the American Civil War, his father did not support President Lincoln. Rhodes even said his father was a "Copperhead". This was a term for Northerners who opposed the war.

This caused some problems for Rhodes's sister. However, she was eventually allowed to marry Mark Hanna. He was a rising businessman and politician from the Republican Party.

Rhodes started attending New York University in 1865. After he graduated, he traveled to Europe. There, he studied at the Collège de France in Paris. While in Europe, he also visited many iron and steel factories. When he returned to the United States, he helped his father. He looked for iron and coal deposits for their family business.

Career as a Historian

In 1874, James Ford Rhodes joined his father's successful iron, coal, and steel businesses in Cleveland. He earned a large fortune from these businesses. By 1885, he decided to retire from business.

Rhodes then moved to Boston. He wanted to be close to its many libraries. He also liked the supportive community of thinkers there. He spent the rest of his life doing historical research and writing. He was never very active in politics himself.

When he looked at the two main political parties during the Reconstruction era, he usually supported the Republican Party. However, in the 1880s, he supported Grover Cleveland. Cleveland was a Bourbon Democrat who favored lower taxes on imported goods. This was interesting because Rhodes himself was connected to the iron and steel industry. Later, he supported Republicans William McKinley in 1896 and Theodore Roosevelt in 1904. In 1912, he supported Woodrow Wilson, who was a Democrat. He also agreed with Wilson's idea for America to join the League of Nations.

Rhodes once told his grandson that he started as a strong Democrat. Then he became a strong Republican. After that, he was a "lukewarm Democrat," and finally, a "lukewarm Republican." His changing views were important. One of the best parts of his many history books is how he looked at both political parties. He found good points and weak points in each one.

His most important work was History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850. This work was published in seven volumes between 1893 and 1906. An eight-volume edition came out in 1920. His single book, History of the Civil War, 1861–1865 (1917), won him a Pulitzer Prize in History in 1918.

Rhodes also joined the American Historical Association. He was chosen to be its president in 1899 for one year.

Understanding History: Rhodes's Approach

James Ford Rhodes mainly focused on national politics in his historical writings. He used newspaper stories and published memories to understand how big decisions were made in the country. He also looked at the strengths and weaknesses of important leaders.

He wrote about corruption he found in the Republican governments during the Reconstruction period. This included governments in Washington, D.C., and the Southern states. He believed that giving all Black people the right to vote right after slavery ended was a mistake. He thought it added to the problems during Reconstruction.

Rhodes's ideas about the role of slavery greatly influenced how people thought about history. Unlike earlier historians who had strong personal feelings about slavery, Rhodes tried to be fair. He argued that slavery was the main reason for the Civil War. He saw it as a political and economic system that leaders and voters put in place. He did not focus much on the enslaved people themselves. Instead, he looked at how politicians and foreign countries used the issue to their advantage.

He believed that the South's cause in the war was wrong. He said that leaders like Calhoun and Davis were responsible for the suffering that came from fighting. By suffering, he meant the deaths and hardships during the war. He did not mean the suffering of enslaved people before the war. He argued that the war was "irrepressible," meaning it was unavoidable by December 1860. He thought it might have been delayed, but it would happen eventually.

For Rhodes, slavery was almost the only cause of the war. He disagreed with Southerners who supported the "Lost Cause" idea. This idea said the rebellion was about states' rights against Northern control. He did not agree with the idea that states had the right to leave the Union. He argued that the South fought to expand slavery. He saw slavery as something wrong based on morals, Christianity, and modern ideas. Rhodes saw slavery as a disaster for the South. However, he felt sympathy for white Southerners, rather than blaming them personally. He believed the South was linked to slavery because of a long history going back centuries.

Rhodes did not think the abolitionist movement was very important. Instead, he focused on mainstream leaders like Daniel Webster. He believed Webster helped create a stronger sense of national unity. Historians have noted that it was Webster's idea of "Liberty and Union" that won in the Civil War. This was different from the abolitionist idea of "no union with slaveholders."

Legacy and Honors

James Ford Rhodes received several honors for his historical work:

- In 1900, he was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.

- In 1901, he received the Loubat Prize from the Berlin Academy of Sciences.

- In 1910, he was given the gold medal of the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

- He received honorary degrees from Oxford and several universities in the United States.

- James Ford Rhodes High School in Cleveland was named after him.

Books by James Ford Rhodes

- "The Battle of Gettysburg." American Historical Review 4#4 1899, pp. 665–677. online

- "Sherman's March to the Sea" American Historical Review 6#3 (1901) pp. 466–474 online

- History of the Civil War, 1861–1865 (1918), one-volume version; Pulitzer Prize online

- History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 - Vol. 1

- History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 - Vol. 2

- History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 - Vol. 3

- History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 - Vol. 4

- History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 - Vol. 5

- History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 - Vol. 6

- History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 - Vol. 7

- History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 - Vol. 8

- The McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, 1897–1909 (1922)

- Historical Essays (1909)

- Lectures on the American Civil War (1913), delivered at Oxford University in 1913.

- History of the Civil War, 1861–1865 (1918), won the Pulitzer Prize for History; It is a completely rewritten history of the war.